James Henry Hubbard, the great Victorian entrepreneur of Dyke entertainment, conceived of linking Poynings to his amusement park with a funicular railway in 1896. It was designed by Charles O. Blaber who was also the engineer for the railway that linked Brighton to the Dyke and it was constructed by a yacht building firm from Southwick. The funicular was built in six months and opened in July 1897. Unlike the aerial cableway that had opened three years earlier, the funicular was not at the leading edge of engineering design. Funicular railways first appeared in the sixteenth century and were in common use throughout the world by the end of the nineteenth century. At least so far as the UK was concerned, 1897 was almost the end of the funicular era. For example, the industrial funicular built at Offham Chalk Pit in East Sussex in 1808 had been shut down in 1870. A company that still builds funiculars today reports that none were constructed between 1902 and 1992. The only unusual feature of the Steep Grade Railway is that it was built inland. Almost all UK passenger funiculars have been built in coastal towns (there are two in Hastings, for example). The best known exception to this seaside generalization is the funicular at Bridgnorth in Shropshire. Like those in Hastings, this little railway remains in use today. But the Bridgnorth funicular links two halves of a town, not a tiny village and an isolated hotel cum funfair. With the benefit of hindsight, the Steep Grade Railway made no economic sense at all.

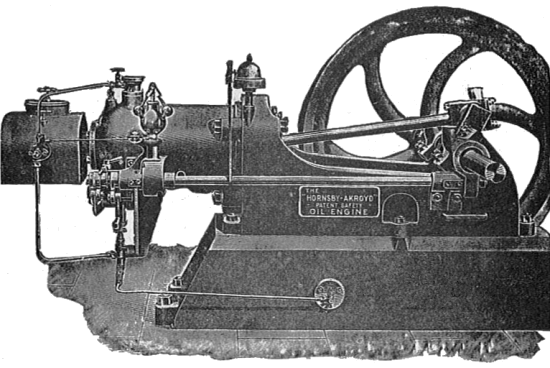

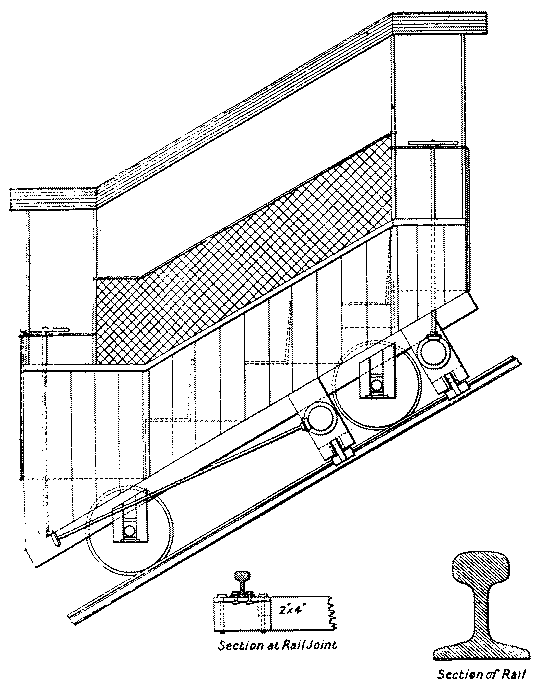

A funicular railway is one in which a cable is looped round a pulley at the top of a slope and two cars are attached, one at either end. One car ascends as the other descends. In the ideal world of school physics, the two cars exactly balance, cables have no mass, and gravity can be removed from the equation. The only role of the associated engine is to overcome the forces of friction. In the real world, the cars almost never balance (passenger numbers will differ, for example), wire cables are heavy, and changes in the gradient mean that the gravitational pull of the cars depends on where they are on the tracks. So the engine has some serious work to do.

The engine in the case of the Steep Grade Railway was a water cooled 25HP Hornsby Ackroyd oil engine similar to the Crossley engine that powered the aerial cableway. The engine ran continuously and was combined with an elaborate clutch and braking system.

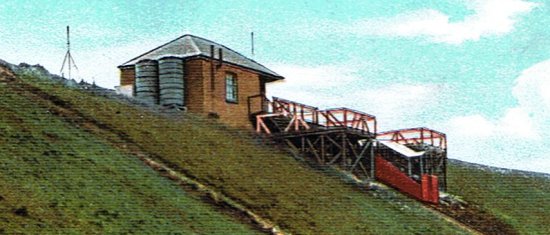

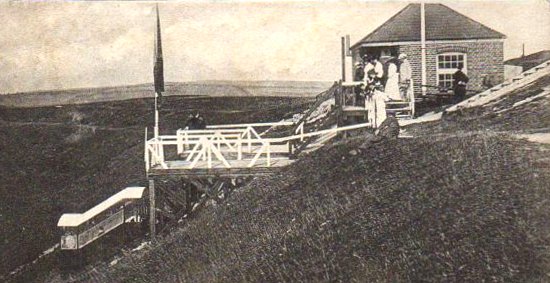

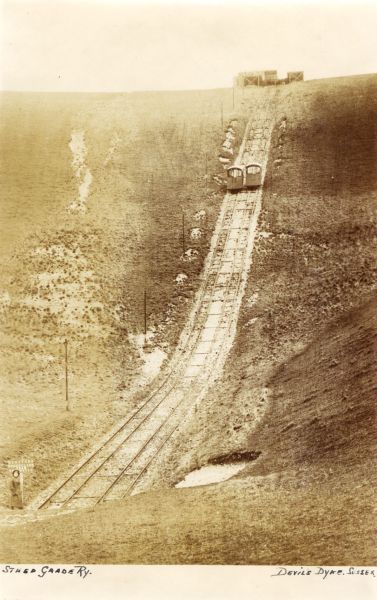

The cars were open and had seats for twelve passengers plus space for a conductor and bicycles. They moved at a sedate 3mph along a 3ft narrow gauge track. The track was 840ft long spread over three different gradients and rose to a height of 395ft. There was a brick platform at the bottom of the track and spring buffers, but no station. A newspaper report published a few days after the opening ceremony tells us that:

The cars do not move rapidly but are kept well under control from first to last. They travel easily, and smoothly, and there is an utter absence of anything in the way of sensation. The journey is certainly a curious one, but that is all. Of course it is pleasant, the cars affording a charming view of the country, and there is the further attraction of the novelty of the whole thing. [Brighton Gazette, 29th July 1897, quoted by Clark 1976, pages 56-58.]

A couple of weeks later, the same newspaper reported (indirectly) that the August bank holiday traffic on the funicular was at the rate of 400-600 passengers per hour. “Good business”, as they put it. But it wasn’t to last.

By 1899 the company that owned and operated the Steep Grade Railway was effectively bankrupt and the railway itself had stopped working. More money was borrowed, the railway was repaired and then, in 1900, it was sold at auction to the original owners for less than 5% of the original building cost. Operations resumed and continued until 1908 or 1909. James Henry Hubbard himself had emigrated to Canada in 1907 after getting into financial difficulties. Although the funicular was used to ship provisions up to the hotel, as well as produce en route to Brighton by rail, it may nonetheless have contributed to Hubbard’s difficulties: the day-trippers from Brighton upon whom he relied for most of his income undoubtedly used it to visit the tearooms in Poynings and Fulking, thus reducing custom at the various eating establishments and other attractions that he ran at the top of the Downs. Meanwhile, a direct bus service to Poynings had been introduced — which surely made the rail route to Brighton over the Dyke seem much less attractive to residents of that village. The Steep Grade Railway was finally dismantled and removed around 1913.

If one stands at the western edge of Poynings on a sunny evening and looks up at the Downs, the route that the funicular track took can still be seen quite clearly, looking much as it did one hundred years ago.

References and further reading:

- Paul Clark (1976) The Railways of Devil’s Dyke, Sheffield: Turntable Publications. Chapter 5, pages 52-62. [Although long out of print, this booklet remains the best source of information about the Steep Grade Railway. It contains plenty of ceremonial, commercial, financial and technical details that are not repeated here.]

- Carole Hampson (2009) Poynings Yesterday. Hove: StewART Publishing Services. Pages 141-142.

- Ernest Ryman (1984) The Devil’s Dyke: A Guide. Brighton: Dyke Publications. Pages 7-9.

- Ernest Ryman (1990) Devil’s Dyke in Old Picture Postcards. Brighton: Dyke Publications. Pages 20-23.

- South Downs National Park Authority (2013) Offham Chalk Pit near Hamsey, East Sussex. SDNPA flyer.

Updated May 2017.

Some other material relevant to the C19 and C20 history of the Dyke: