[The essay that follows comprises a transcription of the twelfth chapter of Bygone Sussex written by William E.A. Axon and published in 1897. The illustrations also come from the book. Apart from a few minor punctuation changes, the text is exactly as it appeared originally.]

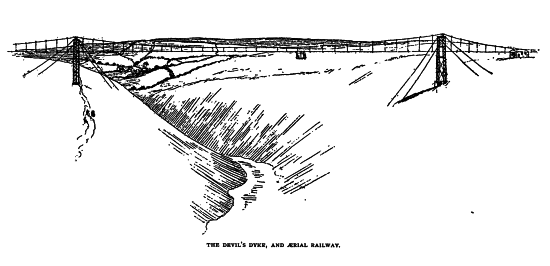

A favourite excursion of those who run down to the seaside to consult “one of the best of physicians” — he whom Thackeray has well described as “kind, cheerful, merry Doctor Brighton” — is to the Devil’s Dyke. To that picturesque spot with an evil name there come pilgrims by coach, by train, and on foot to gaze upon the wide expanding landscape of the Weald, to have their fortunes told by the gipsy “queens” who ply their trade in flagrant defiance of the statute book, or to disport themselves in the somewhat cockney paradise that has arisen on this lovely part of the South Downs. The Dyke itself is the work of Mother Nature in one of her sportive moods, when she seems to imitate or to anticipate the labours of man. Here she has carved out a deep trench that looks as though it were the work of the Anakim. It has its legendary interest also, for the Sussex peasantry hold, or held, that it came into existence by the exertions of the “Poor Man,” as the Father of Evil is here euphemistically called. Looking over the fertile Weald, his Satanic Majesty was grievously offended by the sight of the many churches dotted over the smiling plain, and he decided to cut a passage through the Downs so that the waters of the sea might rush through the opening and drown the whole of the valley. An old woman whose cottage was in the vicinity, hearing the noise made by the labouring devil in his work of excavation, came to her window, and holding her candle behind a sieve, looked out. The “Poor Man” caught sight of the glimmering light, and hastily concluded that the sun was rising. The mediaeval devil could only do his malicious deeds in the dark, and so he slunk away, leaving the Dyke incomplete, as we now see it. Lest anyone should doubt this story, the marks of the “Poor Man’s” footprints are still pointed out on the turf.

A favourite excursion of those who run down to the seaside to consult “one of the best of physicians” — he whom Thackeray has well described as “kind, cheerful, merry Doctor Brighton” — is to the Devil’s Dyke. To that picturesque spot with an evil name there come pilgrims by coach, by train, and on foot to gaze upon the wide expanding landscape of the Weald, to have their fortunes told by the gipsy “queens” who ply their trade in flagrant defiance of the statute book, or to disport themselves in the somewhat cockney paradise that has arisen on this lovely part of the South Downs. The Dyke itself is the work of Mother Nature in one of her sportive moods, when she seems to imitate or to anticipate the labours of man. Here she has carved out a deep trench that looks as though it were the work of the Anakim. It has its legendary interest also, for the Sussex peasantry hold, or held, that it came into existence by the exertions of the “Poor Man,” as the Father of Evil is here euphemistically called. Looking over the fertile Weald, his Satanic Majesty was grievously offended by the sight of the many churches dotted over the smiling plain, and he decided to cut a passage through the Downs so that the waters of the sea might rush through the opening and drown the whole of the valley. An old woman whose cottage was in the vicinity, hearing the noise made by the labouring devil in his work of excavation, came to her window, and holding her candle behind a sieve, looked out. The “Poor Man” caught sight of the glimmering light, and hastily concluded that the sun was rising. The mediaeval devil could only do his malicious deeds in the dark, and so he slunk away, leaving the Dyke incomplete, as we now see it. Lest anyone should doubt this story, the marks of the “Poor Man’s” footprints are still pointed out on the turf.

Here, too, are the evidences of an oval camp with massive rampart and broad fosse, occupied probably by the Romans, whose coins have been found, and by still earlier warlike inhabitants of the district. When the eye has satisfied itself with the fine prospect, landward and seaward, we may undertake a short pilgrimage to a little known Ruskin shrine. Below us northward are the villages of Poynings, Fulking, and Edburton. The last is known to archaeologists for its leaden font, which is said to date from the end of the twelfth century. Here Laud, the pious, ambitious, unscrupulous, and unfortunate prelate, is said to have officiated. To him is attributed the gift of the pulpit and altar rails in the church.

Here, too, are the evidences of an oval camp with massive rampart and broad fosse, occupied probably by the Romans, whose coins have been found, and by still earlier warlike inhabitants of the district. When the eye has satisfied itself with the fine prospect, landward and seaward, we may undertake a short pilgrimage to a little known Ruskin shrine. Below us northward are the villages of Poynings, Fulking, and Edburton. The last is known to archaeologists for its leaden font, which is said to date from the end of the twelfth century. Here Laud, the pious, ambitious, unscrupulous, and unfortunate prelate, is said to have officiated. To him is attributed the gift of the pulpit and altar rails in the church.

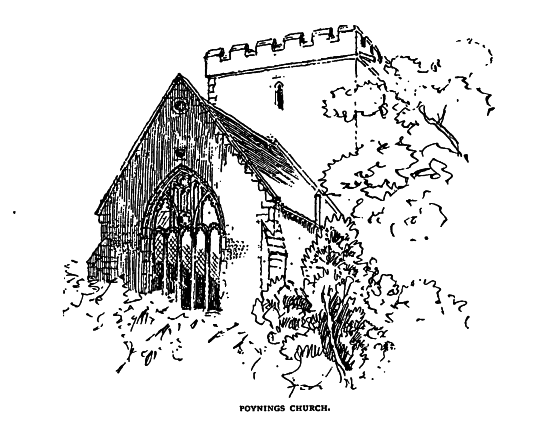

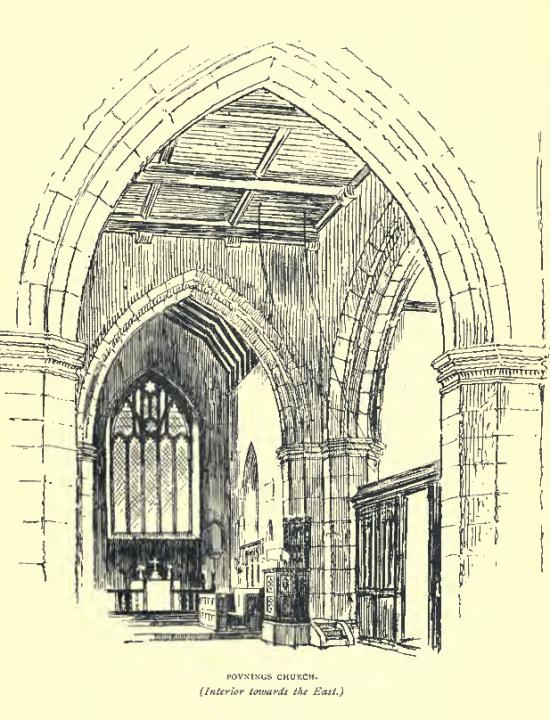

Descending the steep slope of the South Downs, and breathing the invigorating air which has won so many praises, we are soon in a rustic road that leads to the church of Poynings. The church is one of great interest and dignity. It is early Perpendicular, cruciform, and has a square central tower. The alms box is an ancient thurible of carved wood. “Puningas” — and Punnins is still a local pronunciation — was restored, with other lands, to the thane Wulfric by King Eadgar, who pardoned some of his vassal’s slight offences in consideration of receiving 120 marcs of the most approved gold. When Domesday Book was compiled the manor was held by a feudatory of the powerful William de Warren. Inside the church are some monuments of those stalwart soldiers, the Poynings, and outside there are still traces of their ancient home from the time of Stephen to that of Henry VII. Their name is enduringly written in our history in “Poyning’s law“. In 1294, Sir Michael, lord of this manor, was summoned to Parliament as the first Baron de Ponynges. His son Thomas was slain in the great sea-fight at Sluys. The son of this soldier was Sir Michael, the third baron, who was with Edward III at Crecy, and at the surrender of Calais in 1347. When he returned to his castle, he was appointed one of the guardians of the Sussex coast, then in danger of a French invasion. When he died in 1368, he bequeathed “to him who may be my heir” a “ruby ring which is the charter of my heritage of Poynings”. The barony passed by the distaff to the Earls and Dukes of Northumberland. Sir Edward Poynings, a grandson of the sixth baron, had his home at Ostenhanger in Kent. Whilst Lord Deputy of Ireland, he induced the Irish Parliament, in 1494-5, to pass a measure by which all the laws of England were made to be of force in Ireland, and no bill could be introduced into the Irish Parliament without the previous sanction of the Council of England. He died in 1521 the Governor of Dover Castle. “Who more resolved than Poynings?” asks Lloyd, “whose vigilancy made him master of the Cinque Ports, as his valour advanced him general of the low-county forces, whom he led on to several services with such success, and brought off, with the loss of not above an hundred men, with honour from the Lady Margaret, and applause from the whole country.” Poynings passed by sale to the Brownes, and by failure of heirs reverted to the crown in 1797.

Descending the steep slope of the South Downs, and breathing the invigorating air which has won so many praises, we are soon in a rustic road that leads to the church of Poynings. The church is one of great interest and dignity. It is early Perpendicular, cruciform, and has a square central tower. The alms box is an ancient thurible of carved wood. “Puningas” — and Punnins is still a local pronunciation — was restored, with other lands, to the thane Wulfric by King Eadgar, who pardoned some of his vassal’s slight offences in consideration of receiving 120 marcs of the most approved gold. When Domesday Book was compiled the manor was held by a feudatory of the powerful William de Warren. Inside the church are some monuments of those stalwart soldiers, the Poynings, and outside there are still traces of their ancient home from the time of Stephen to that of Henry VII. Their name is enduringly written in our history in “Poyning’s law“. In 1294, Sir Michael, lord of this manor, was summoned to Parliament as the first Baron de Ponynges. His son Thomas was slain in the great sea-fight at Sluys. The son of this soldier was Sir Michael, the third baron, who was with Edward III at Crecy, and at the surrender of Calais in 1347. When he returned to his castle, he was appointed one of the guardians of the Sussex coast, then in danger of a French invasion. When he died in 1368, he bequeathed “to him who may be my heir” a “ruby ring which is the charter of my heritage of Poynings”. The barony passed by the distaff to the Earls and Dukes of Northumberland. Sir Edward Poynings, a grandson of the sixth baron, had his home at Ostenhanger in Kent. Whilst Lord Deputy of Ireland, he induced the Irish Parliament, in 1494-5, to pass a measure by which all the laws of England were made to be of force in Ireland, and no bill could be introduced into the Irish Parliament without the previous sanction of the Council of England. He died in 1521 the Governor of Dover Castle. “Who more resolved than Poynings?” asks Lloyd, “whose vigilancy made him master of the Cinque Ports, as his valour advanced him general of the low-county forces, whom he led on to several services with such success, and brought off, with the loss of not above an hundred men, with honour from the Lady Margaret, and applause from the whole country.” Poynings passed by sale to the Brownes, and by failure of heirs reverted to the crown in 1797.

From Poynings there is a road leading to Fulking, and on the way many capital views of the round breasts of the South Downs can be had. Fulking is merely a hamlet of the parish of Edburton, and is a somewhat debateable land, for whilst it is situated in the Rape of Lewes, the parish to which it is a tything, is in the Rape of Bramber. It contains about 1,330 acres of arable, pasture, and down land. In Domesday Book it is mentioned under the name of Fochinges, and was then held of William de Warren by one Tezelin, of whom nothing more is known. It was situated in Sepelei (Edburton ?), which William de Braose held. Before the Normans came, Harold held it in the time of King Edward. It was assessed, both in the Saxon and Roman times, at three hides and a rood.

It is a striking evidence of English persistence. This little hamlet has continued for more than eight centuries; how many more no one can say. It has not even been important enough to have its own separate church, but, nevertheless, it has persisted manfully in the struggle for existence. A winding street of mingled villas and cottages is the Fulking of to-day, nestling in trees, beneath the sheltering wings of the South Downs, and apparently as unconscious of the gaieties of Brighton as if it were a thousand miles away.

Fulking is the end of our Ruskin pilgrimage, for here on the right hand of the road is a fountain with a red marble tablet, on which is inscribed:

TO THE GLORY OF GOD

AND IN HONOUR OF

JOHN RUSKIN.

PSALM LXXVIII

THAT THEY MAY SET THEIR HOPE

IN GOD AND NOT FORGET.

BUT KEEP HIS COMMANDMENTS

WHO BROUGHT STREAMS ALSO OUT OF THE ROCK.

John Ruskin, who besides being a teacher of art and ethics, is also a geologist, was appealed to by some friends of Fulking who were anxious as to its water supply. There is an abundant gathering ground, but Nature appeared to be elusive, and the water courses ran other ways. Mr. Ruskin’s aid was effectual, and the ancient hamlet has now its own abundant supply. Lower down the road, and past the hostelry of the “Shepherd Dog” — a true South Down sign — is the storage house of Fulking Waterworks. On the tablet of this we read:

HE SENDETH SPRINGS

INTO THE VALLEYS

WHICH RUN AMONG THE HILLS

OH THAT MEN WOULD

PRAISE THE LORD

FOR HIS GOODNESS

The exact source of the first inscription will be seen in Psalm cxxviii, 7 and 16; and of the second in Psalm civ, 10, and cvii, 8, 15, 21, 31.

Those who honour Ruskin as a great teacher of truth and righteousness, will find something appropriate in this memorial of him in the solitary street of the little hamlet, whose feudal lord once upon a time was Harold, the last of the Saxon kings.

Reference

- William E.A. Axon (1897) Bygone Sussex. London: William Andrews & Co., pages 137-143 [PDF].