Gules fleur de lis argent: the arms of the wealthy and influential Aguillon family who held the manor of Perching for much of the 13th century.

The four manors of Edburton, in common with others found along the South Downs, are oddly arranged to the modern eye. Together with Fulking*, they partition the parish into long thin irregularly shaped strips running from south to north. The explanation for this topography lies in the fact that the manors owed their existence to farming. Each manor was a self-contained mixed farming zone:

Each had its chunk of Down pasture, its rich malm and greensand arable under the Downs, its sticky wooded patch of gault clay beyond, and fertile lower greensand at the northern end. .. Each of the farmsteads had a daughter farm to the north on the lower greensand — Truleigh Sands, Edburton Sands, Nettledown, and Perching Sands. The woods of Tottington Longlands and Perching Hovel mark the poorly drained gault clay.

[Bangs 2008, page 216]

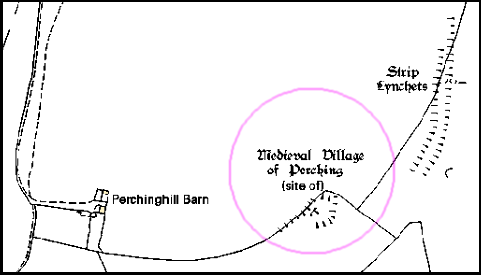

Sheep were grazed on the Downs, the northern escarpment provided chalk for lime and springs for a water supply, and the weald provided suitable land for crops, cattle, and rabbit warrens as well as woods providing timber and charcoal and a home for swine. In addition to the northern daughter farms listed by Bangs, at least some of the manors once had southern daughter farms located on the top of the Downs. Thus Paythorne had Summersdeane which had survived as a farm from Saxon times until Canadian tanks used it for target practice during WWII. In the case of Perching, the southern farm was probably located at the deserted medieval settlement to the east of the modern, but now dilapidated, Perching Hill Barn buildings.

The site of the medieval settlement on Perching Hill. Note the strip lynchets — ploughed cultivation terraces. There was an underground water supply available, currently attested by the well adjacent to Perching Hill Barn.

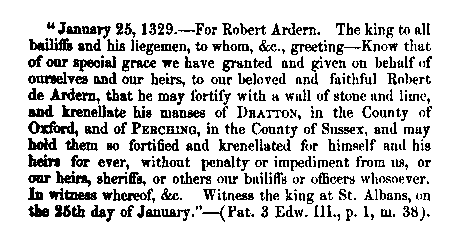

Perching was now in the hands of a powerful family of considerable note. They were important in the county, for thirteen legal decisions are extant on their tenure of properties in Sussex other than Edburton between 1190 and 1298. They also held estates elsewhere, from one of the chief of which, Addington in Surrey, much can be learned which is of interest for Edburton. They were important to the crown as holding Addington by a service of cookery at coronations. The obligation was no doubt a proud privilege, just as to this day are the duties of bearing certain of the insignia at coronations. The duty is defined as “a sergeantry of making a hotch-potch in a yellow dish in the king’s kitchen on the day of his coronation or by deputy”. Perching was not held by this service, but the succession at Addington and Perching had been the same. The first Norman tenant of both had been Tezelin, the Conqueror’s cook. It is not only that the two manors were so closely connected, nor even the flavour of the kitchen, that is the most significant, but that the family was so closely tied to the crown at a time when so many of the feudal lords were in revolt. Robert, the son of William, and his heir and successor at Perching, was a devoted royalist, in whom the king had such confidence as to allow him to fortify his manor-house. In 1264 a licence [to crenellate] was granted. Meanwhile, Robert had died, in 1261, and in 1268 the licence was renewed to his son, also named Robert. [Howe 1958, pages 8-9]

In contrast to Victorian times, the desire to crenellate a manor was not an aesthetic matter, nor an academic one. The king would have wished to ensure that his supporters were in a position to defend themselves. This was a period when the king and the barons were in dispute. Robert Aguillon was loyal to the king but his overlord, the Earl of Warenne was a militant baron. Relations between them were not good as this document of a prosecution for trespass from 1274 demonstrates:

To the sheriff of Sussex. Whereas the king, at the prosecution of Robert Aguillon, lately ordered him to move the men of John de Warenne, earl of Surrey, archers and other armed men, who wander about Robert’s manor of Percynges and about his other lands, and lie in wait by day and night for his men, and aggrieve and disquiet them, from the said manor and lands, and the archers and other armed men, although warned by the sheriff on the king’s behalf to depart quietly from the manor and lands, still remain there doing worse damage to Robert and his men, whereat the king is moved: the king therefore orders the sheriff, if the archers and men still remain there and refuse to depart, to take them and keep them in prison until otherwise ordered. [Calendar of the Close Rolls, Henry III, 27th March 1274, quoted by Howe 1958, page 9]

When the younger Robert died, in 1286, Perching manor alone had been providing him with an income of around £100,000 per annum in today’s money (calculated on the basis of the relative price of eggs). And he was the lord of many manors.

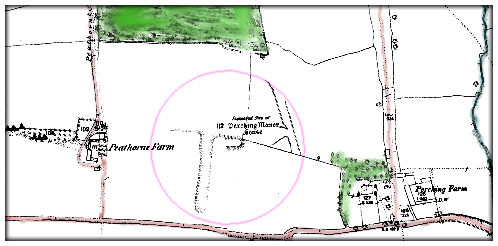

The building that the Aguillons sought and gained permission to fortify was not, of course, the house that we know as Perching Manor today. The thirteenth century Aguillon manor house stood midway between Paythorne and Perching farms in what is now a field, Frog Holt, immediately south of Perching Hovel Wood. Howe remarks that “it is not known when [it] ceased to be occupied or when it was demolished” [1958, page 33]. There’s not a lot left to see though a portion of the moat persists.In the fourteenth century, Perching passed into the hands of the de Arderns, then Sir Michael de Poynings and thence, by marriage, to the Earls of Northumberland. When the 6th Earl was executed for treason in the sixteenth century, all his property was confiscated by the crown. The king then granted Perching to the father of the first Lord Montague (of Cowdray). When the last Lord Montague died, at the end of the eighteenth century, the estate returned to the crown. Throughout the seventeenth century, Perching was held by the Colstock family as tenants of the Montagues. During the time of the Rump Parliament, Thomas Colstock, a royalist, found himself having to appear before the sinister but delightfully named Committee for Compounding with Delinquents in order to retain control of Perching.*The manorial status of Fulking is complex. It was once a component of the manor of Shipley, then became detached and was eventually absorbed by Perching [see Howe 1958, page 6 for the details]. The Old Farmhouse may have been the manor house.

References:

- Dave Bangs (2008) A Freedom to Roam Guide to the Brighton Downs. Portsmouth: Bishop Printers.

- F.A. Howe (1958) A Chronicle of Edburton and Fulking in the County of Sussex. Crawley: Hubners Ltd. [The definitive source on the early history of Perching. Most of the information presented above comes from Howe’s book.]

- L.F. Salzman, ed. (1940) A History of the County of Sussex, Volume 7: The rape of Lewes. London: Victoria County History, pages 202-204. [This contains a lot of detail on the early history of Perching, albeit in a much less readable manner than Howe. But, unlike Howe, it is just a click away.]

Updated 2nd March, 2013.

Currently popular local history posts: