“The little church at the foot of the grey-green down”, or so runs the title of this photograph of St. Andrew’s, Edburton in a 1922 edition of The Roadmender. But was it?

Although The Roadmender is suffused with a sense of location it is, more often than not, inexplicit as to exactly which locations the author had in mind [1]. But readers, reviewers, book illustrators and authors of travel guides are curious about such matters. They had to wait ten years even to discover who the author was. That information was released in 1912 by her literary executor, against the author’s express wish, as an antidote to the misinformed speculation that had developed around the book. One reference in the book was unambiguous even before her identity became known — from the house in Shermanbury she reports hearing the bells of “the monastery where the Bedesmen of St. Hugh watch and pray” (page 44). Other references, to the Thames and the Downs are less specific. Books with titles like The Roadmender Country (Lorma Leigh, 1922) and The Roadmender’s Country (George Bramwell Evens, 1924) were published to sate the geographical curiosity of her readers some two decades after the book that inspired them was originally published.

The location that concerns this post is the subject of the following passage:

On Sundays my feet take ever the same way. First my temple service, and then five miles tramp over the tender, dewy fields, with their ineffable earthy smell, until I reach the little church at the foot of the grey-green down. Here, every Sunday, a young priest from a neighbouring village says Mass for the tiny hamlet, where all are very old or very young — for the heyday of life has no part under the long shadow of the hills, but is away at sea or in service. There is a beautiful seemliness in the extreme youth of the priest who serves these aged children of God. He bends to communicate them with the reverent tenderness of a son, and reads with the careful intonation of far-seeing love. To the old people he is the son of their old age, God-sent to guide their tottering footsteps along the highway of foolish wayfarers; and he, with his youth and strength, wishes no better task. Service ended, we greet each other friendly — for men should not be strange in the acre of God; and I pass through the little hamlet and out and up on the grey down beyond. Here, at the last gate, I pause for breakfast; and then up and on with quickening pulse, and evergreen memory of the weary war-worn Greeks who broke rank to greet the great blue Mother-way that led to home. I stand on the summit hatless, the wind in my hair, the smack of salt on my cheek, all round me rolling stretches of cloud-shadowed down, no sound but the shrill mourn of the peewit and the gathering of the sea. [The Roadmender, pages 10-11]

Over the last hundred years, it has been widely assumed, by those who have had occasion to care about such matters, that “the little church at the foot of the grey-green down” is St. Andrew’s at Edburton. Writing in the Observer in 1921, Arthur Anderson made the claim explicitly. Such was also clearly the working assumption of Will F. Taylor, the photographer who did the illustrations for a 1922 US edition published by E.P. Dutton and whose image of St. Andrew’s can be seen at the top of this post. In the 1950s F.A. Howe, who lived right next door to St. Andrew’s, reported that devotees of the book would occasionally turn up at the church. The 1999 edition of Tony Wales’s survey of West Sussex villages provides a modern example and is quite explicit: “St. Andrew .. is the little grey church in Michael Fairless’s strange Sussex book” (page 90).

As Howe notes, Anderson was to withdraw his claim just three years after he originally made it:

When I wrote my Observer articles, I hazarded the suggestion that this little church could be no other than Edburton, which fits, and alone fits, the geographical conditions, but I have learned since that though Michael Fairless had in mind an actual church it was one in another English county, far from Sussex. My suggestion has, however, not only been adopted by others; it has been expanded into an assertion that Michael Fairless herself often kneeled before the altar here [2]. For this statement there will henceforth be no warrant, though I daresay the suggestion, once having been made, will still be repeated and to Edburton will still be attributed this association. [Quoted by Howe 1958, page 61.]

Anderson is probably incorrect in taking full responsibility for the original claim — others surely made the same inference that he had. But his pessimism about ever getting it corrected it was clearly appropriate. The myth lives on.

The White Gate, an etching by Will G. Mein from the endpapers of Scott Palmer & Haggard 1913. This was a real gate, visible from MB’s room in Mockbridge House. MB used it as a symbol of the point of transition from life on earth to “a land from which there is no return” (page 158).

Footnotes

[1] Likewise, the book rarely names contemporary figures. But MB makes an exception for John Ruskin who had died at exactly the point that she had begun writing The Roadmender. She seems to have had no fear about encountering him in the hereafter:

John Ruskin scolded and fought and did yeoman service, somewhat hindered by his over-good conceit of himself. [The Roadmender, page 139]

[2] And, of course, MB’s grave is not to be found in the churchyard at St. Andrew’s, Edburton. There is no reason for it to be there. It was her wish that she be buried at St. Giles, Shermanbury but the old churchyard was closed for interments at the time of her death (The Landmark VI.1, 1924, page 602). Instead, her grave is to be found at St. James, Ashurst.

References

- Alan Barwick (2013) “Notes for The Roadmender talk”. Henfield Museum: manuscript. [This paper is the single best source for the biographical details of MB’s brief life and is based, in part, on a recent bequest of documents to the museum. The illustrated talk itself includes a remarkable collection of modern and historical images that document aspects of that life.]

- Michael Fairless (1902) The Roadmender. London: Duckworth. [As noted in the text above, the book remains readily available. You can also download it as a PDF file, or read it on the web.]

- F.A. Howe (1958) A Chronicle of Edburton and Fulking in the County of Sussex. Crawley: Hubners Ltd, page 61. [Howe’s single paragraph on this topic inspired the present post — which also borrows the section title he used in his contents list.]

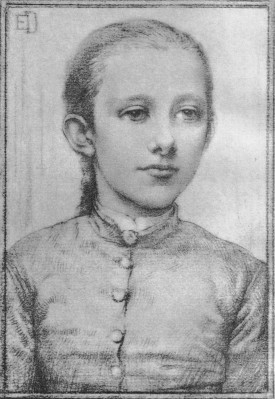

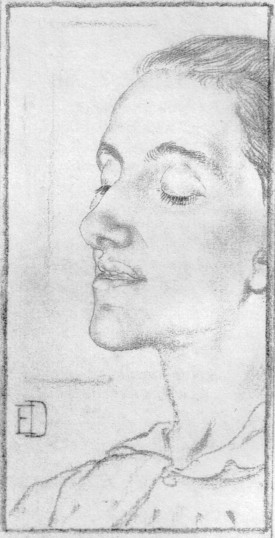

- W. Scott Palmer & A.M. Haggard (1913) Michael Fairless: Her Life and Writings. London: Duckworth (PDF). [The first author was MB’s close friend and literary executor, Mary Dowson, and the second was MB’s eldest sister. The book includes two portraits of MB by Elinor Dowson, both reproduced above. MB was known as Marjorie Dowson for the final few years of her life.]

- Tony Wales (1999) The West Sussex Village Book. Newbury: Countryside Books, page 90.

Currently popular local history posts: