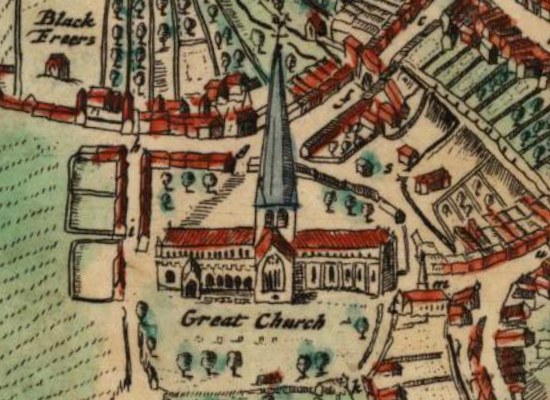

George Keith (1639?–1716), ‘Christian quaker’ and Anglican missionary, was born about 1639 in Scotland, probably in Aberdeenshire, but not at Aberdeen (Barclay, Truth Triumphant, 1692, p. 588). Educated at Marischal College, Aberdeen, where he graduated M.A., he was a class-fellow of Gilbert Burnet in the period 1653–7. He was a good mathematician, and an oriental scholar. On leaving college he became tutor and chaplain in a noble family. Designed for the presbyterian ministry, but apparently not ordained, he adopted the tenets of the quakers, first promulgated in the Aberdeenshire district towards the end of 1662 by William Dewsbury There is nothing to show how he was drawn to quakerism; the date of his ‘conviction’ is almost coincident with the restoration of episcopacy in the Aberdeen diocese. In 1664 he went on a mission to quakers at Aberdeen, and was imprisoned for ten months in the tolbooth. Nevertheless in 1665 he attempted to address the assembled congregation at ‘the great place of worship,’ probably St. Nicholas’s Church, Aberdeen, when he was knocked down by the bell-ringer. For preaching in the graveyard at Old Deer, Aberdeenshire, he was locked in the ‘thieves-hole,’ a windowless dungeon. In 1669 he was a prisoner in the tolbooth at Edinburgh.

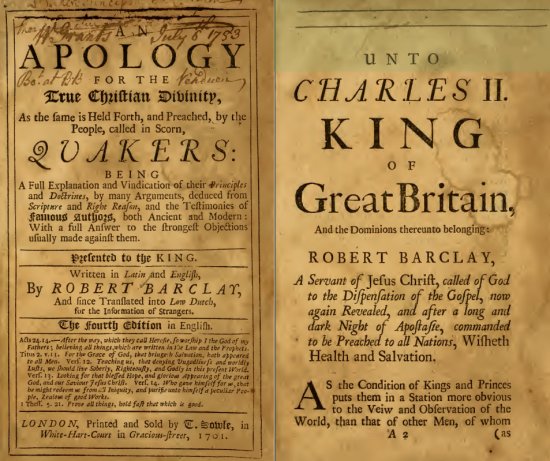

After the adhesion of Robert Barclay (1648–1690) to quaker principles in 1667, Keith exercised an important influence in shaping the phraseology of the future apologist, and providing him with illustrative materials for his great work. Even the substance of Barclay’s doctrine shows traces of the christology of Keith, who had adopted from Postel the idea of a strong distinction between the celestial and the earthly Christ. Keith was probably the author of the English translation (1674) of Pocock’s ‘Philosophus Autodidactus,’ from which he supplied Barclay with the story of Hai Ebn Yokdan (Apology, prop. v. vi. § 27). On 14 Feb. 1675 he took part with Barclay at an open-air discussion ‘in Alexander Harper his close,’ Aberdeen, when Barclay’s ‘theses,’ the substratum of his Apology, were defended against a number of divinity students. Two short treatises of this period, ‘Quakerism No Popery,’ a reply to John Menzies’s ‘Roma Mendax’ (1675) and ‘Quakerism Confirmed’ (1676), were the joint work of Barclay and Keith. At the end of 1676 the latter was again imprisoned, with Barclay and others, in ‘the chapel,’ or lower prison, of Aberdeen.

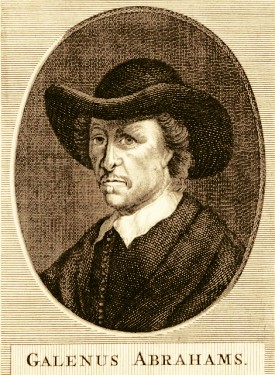

Keith had married Elizabeth, daughter of William Johnston, M.D., of Aberdeen, by his wife, Barbara Forbes, and on gaining his liberty he went to England with his wife and Robert Barclay to attend the ‘yearly meeting’ in June 1677.  Keith was anxious to secure the doctrinal unity of the quaker movement, by means of a joint confession of faith, an idea which evidently did not commend itself to George Fox (1624–1691). Barclay and the Keiths joined Fox, Penn, and others in an expedition to Holland, sailing from Harwich on 25 July, and reaching Rotterdam on 28 July. Here they remained to superintend some printing, rejoining Fox for the ‘quarterly meeting’ at Amsterdam on 2 Aug. The establishment of a ‘yearly meeting’ for Germany followed, and on 6 Aug. Keith, Barclay, and Penn set out on a missionary tour, with Benjamin Furly as interpreter. Barclay soon returned to England with Elizabeth Keith. Keith and Penn pushed on to Heidelberg. On their return to Amsterdam they held a discussion with Galenus Abrahams, a Mennonite teacher of Socinian leanings. They embarked for Harwich with Fox on 21 Oct.

Keith was anxious to secure the doctrinal unity of the quaker movement, by means of a joint confession of faith, an idea which evidently did not commend itself to George Fox (1624–1691). Barclay and the Keiths joined Fox, Penn, and others in an expedition to Holland, sailing from Harwich on 25 July, and reaching Rotterdam on 28 July. Here they remained to superintend some printing, rejoining Fox for the ‘quarterly meeting’ at Amsterdam on 2 Aug. The establishment of a ‘yearly meeting’ for Germany followed, and on 6 Aug. Keith, Barclay, and Penn set out on a missionary tour, with Benjamin Furly as interpreter. Barclay soon returned to England with Elizabeth Keith. Keith and Penn pushed on to Heidelberg. On their return to Amsterdam they held a discussion with Galenus Abrahams, a Mennonite teacher of Socinian leanings. They embarked for Harwich with Fox on 21 Oct.

It was probably on his way back to Scotland that Keith visited Anne Conway, viscountess Conway, at Ragley Hall, Warwickshire. She sent a contribution towards the building of a quaker meeting-house at Aberdeen, and from her physician, Francis Mercurius van Helmont, Keith derived a belief in the pre-existence and transmigration of souls. At an earlier stage in the quaker movement opinions not less erratic might have passed without challenge; but though Keith never obtruded his new position, defending it rather as providing an opportunity for the salvation of those unreached by Christ in a prior term of existence, it was regarded as a heresy.

About 1680 Keith started a boarding-school, first at Edmonton, Middlesex, then at Theobalds, Hertfordshire. For refusing to take the oath he was imprisoned in 1682. The apologist placed his eldest son, Robert Barclay, at his school in 1683. Next year Keith was again imprisoned in Newgate. Some four years later he emigrated to America, settling at Philadelphia in 1689 as schoolmaster.

This migration was the turning-point in Keith’s career. Sewel connects his alienation from the quakers with condemnatory expressions, harsher than he could brook, directed by certain individuals against his doctrine of transmigration. But in a publication at Philadelphia in 1689 (‘The Presbyterian … Churches in New England … Brought to the Test,’ &c.) his allusions to a use of the Lord’s Supper (in the form of an agape), though not exceeding the liberty allowed in Barclay’s Apology (prop. xiii. §§ 8, 11), are significant of a tendency of his mind which brought him out of harmony with quaker modes of thought. On other points, denying the sufficiency of the inner light, he inclined to a stronger assertion of historic and dogmatic Christianity than was palatable to some Philadelphia quakers. He made enemies of William Stockdale (d. 1693), a prominent elder from the north of Ireland, and Thomas Lloyd (d. 10 Sept. 1694), the deputy-governor. The deaths of Barclay and Fox, within a few months of each other, left no one (1691) in the quaker community to whom Keith was inclined to submit, and he aspired to a position of leadership.  The ‘yearly meeting’ at Philadelphia, in September 1691, upheld Keith against Stockdale, while blaming the angry spirit shown by both. Nevertheless in the ‘monthly meeting’ Thomas Fitzwalter, a quaker minister, arraigned as heresy Keith’s denial of the sufficiency of the light within. The peace of the community was seriously endangered; hence Lloyd and the magistrates intervened, with no goodwill to Keith. But it was clear that the majority of ministers and elders was on his side. Accordingly the magistrates gave judgment against Stockdale and Fitzwalter, suspending them from their functions till they had made public amends for their action against Keith. This they ultimately declined to do, but persisted in exercising their ministry, stigmatising their opponents as Keithians. From this point Mr. Joseph Smith, the quaker bibliographer, dates Keith’s ‘apostasy.’ Keith, who made no effort to exclude his opponents, confidently expected their return. Fearing the consequences of the rupture, the magistrates convened a special court of twenty-eight ministers and magistrates, including some who, like Lloyd, and Samuel Jenings, the leading spirit against Keith, held both functions. This court at its first sitting, on 20 June 1692, condemned Keith unheard, and interdicted him from preaching. Keith held his ground. Assisted by Thomas Budd he published a ‘Plea of the Innocent’ and other pamphlets, and maintained distinct meetings for worship, his followers denying that they were separatists. William Bradford, the printer of his ‘Appeal’ to the ‘yearly meeting,’ was sent to prison. Keith and his friends, calling themselves ‘Christian quakers,’ held their own ‘yearly meeting’ at Burlington on 7 Sept. Fresh adherents came to them from the Mennonite settlers in Pennsylvania. After various wrangles, a new court, presided over by Jenings, sat at Philadelphia from 9 to 12 Dec., when Keith and others were condemned in a fine (not exacted) for personalities against Lloyd, and for denying the magistrates’ right to arm the Indians in self-protection, and to employ hired force against privateers; a position which shows the influence of Mennonite tenets. To the same influence may be ascribed a collective ‘Exhortation & Caution to Friends against buying or keeping of Negroes,’ issued by the Keith party on 13 Oct. 1693, and apparently the earliest quaker protest against slavery.

The ‘yearly meeting’ at Philadelphia, in September 1691, upheld Keith against Stockdale, while blaming the angry spirit shown by both. Nevertheless in the ‘monthly meeting’ Thomas Fitzwalter, a quaker minister, arraigned as heresy Keith’s denial of the sufficiency of the light within. The peace of the community was seriously endangered; hence Lloyd and the magistrates intervened, with no goodwill to Keith. But it was clear that the majority of ministers and elders was on his side. Accordingly the magistrates gave judgment against Stockdale and Fitzwalter, suspending them from their functions till they had made public amends for their action against Keith. This they ultimately declined to do, but persisted in exercising their ministry, stigmatising their opponents as Keithians. From this point Mr. Joseph Smith, the quaker bibliographer, dates Keith’s ‘apostasy.’ Keith, who made no effort to exclude his opponents, confidently expected their return. Fearing the consequences of the rupture, the magistrates convened a special court of twenty-eight ministers and magistrates, including some who, like Lloyd, and Samuel Jenings, the leading spirit against Keith, held both functions. This court at its first sitting, on 20 June 1692, condemned Keith unheard, and interdicted him from preaching. Keith held his ground. Assisted by Thomas Budd he published a ‘Plea of the Innocent’ and other pamphlets, and maintained distinct meetings for worship, his followers denying that they were separatists. William Bradford, the printer of his ‘Appeal’ to the ‘yearly meeting,’ was sent to prison. Keith and his friends, calling themselves ‘Christian quakers,’ held their own ‘yearly meeting’ at Burlington on 7 Sept. Fresh adherents came to them from the Mennonite settlers in Pennsylvania. After various wrangles, a new court, presided over by Jenings, sat at Philadelphia from 9 to 12 Dec., when Keith and others were condemned in a fine (not exacted) for personalities against Lloyd, and for denying the magistrates’ right to arm the Indians in self-protection, and to employ hired force against privateers; a position which shows the influence of Mennonite tenets. To the same influence may be ascribed a collective ‘Exhortation & Caution to Friends against buying or keeping of Negroes,’ issued by the Keith party on 13 Oct. 1693, and apparently the earliest quaker protest against slavery.

The controversy reached London. To allay it an authorised statement of Christian doctrine, drawn up by George Whitehead, was issued in 1693; a shorter statement was presented to parliament in December of that year. The influence of Keith’s views is seen in the minutes of the Aberdeen ‘quarterly meeting,’ which record on 9 Sept. 1693 the establishment of ‘a consolatory repast (as among the primitive Christians) from house to house.’ Keith came to London in 1694, attending the ‘yearly meeting,’ which was held on 3 May and adjourned to 11 June, when fruitless efforts were made to end the division. At length, on 15 May 1695, Keith, till he should make public amends, was disowned by the ‘yearly meeting,’ not ‘for his doctrinal opinions, but for his unbearable temper and carriage’ (Barclay, Inner Life, p. 375), and for his refusal to withdraw his charges against Philadelphia quakers.

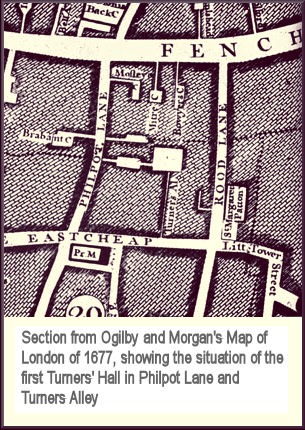

Keith, on his part, disowned the ‘yearly meeting.’  He obtained a meeting-house at Turners’ Hall, Philpot Lane, Fenchurch Street, which had been vacated by general baptists in June 1695. Here, while retaining the quaker name, garb, and speech, he administered baptism and the Lord’s Supper. His meeting-house was thronged; his sermons were continuous attacks upon the orthodoxy of quakers, especially of Penn, whom he accused of deism. From time to time he published ‘narratives’ of his proceedings at Turners’ Hall. In 1698 and 1699 he went on controversial tours among the quakers in the provinces. At Bristol, in August 1699, he was threatened with the law if he entered the meeting-house, though he promised to make no disturbance. On 5 May 1700 he preached a ‘farewell sermon’ at Turners’ Hall, giving his reasons for conforming to the established church. He was at once ordained by Henry Compton (1632–1713), bishop of London, and preached his first sermon as an Anglican clergyman on 12 May at St. George’s, Botolph Lane, Lower Thames Street. Sewel notes as remarkable that he sometimes preached in a surplice. He continued to make tours in order to denounce quakerism, visiting Bristol and Colchester in 1700 and 1701; he claims to have led five hundred quakers to conform. His last ‘narrative’ of proceedings at Turners’ Hall is dated 4 June 1701. His successor in the use of the meeting-house was Joseph Jacob.

He obtained a meeting-house at Turners’ Hall, Philpot Lane, Fenchurch Street, which had been vacated by general baptists in June 1695. Here, while retaining the quaker name, garb, and speech, he administered baptism and the Lord’s Supper. His meeting-house was thronged; his sermons were continuous attacks upon the orthodoxy of quakers, especially of Penn, whom he accused of deism. From time to time he published ‘narratives’ of his proceedings at Turners’ Hall. In 1698 and 1699 he went on controversial tours among the quakers in the provinces. At Bristol, in August 1699, he was threatened with the law if he entered the meeting-house, though he promised to make no disturbance. On 5 May 1700 he preached a ‘farewell sermon’ at Turners’ Hall, giving his reasons for conforming to the established church. He was at once ordained by Henry Compton (1632–1713), bishop of London, and preached his first sermon as an Anglican clergyman on 12 May at St. George’s, Botolph Lane, Lower Thames Street. Sewel notes as remarkable that he sometimes preached in a surplice. He continued to make tours in order to denounce quakerism, visiting Bristol and Colchester in 1700 and 1701; he claims to have led five hundred quakers to conform. His last ‘narrative’ of proceedings at Turners’ Hall is dated 4 June 1701. His successor in the use of the meeting-house was Joseph Jacob.

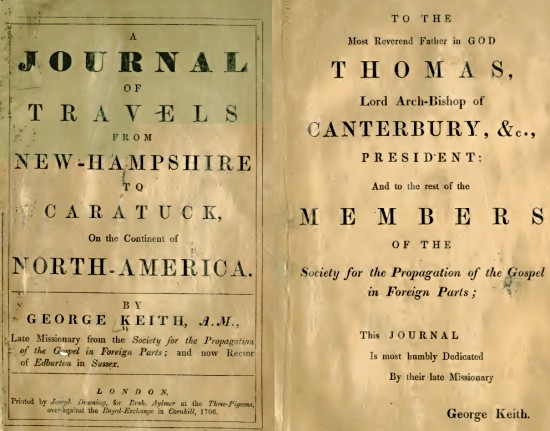

In 1702 Keith returned to America as one of the first missionaries sent out by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (incorporated 1701). A curious account is given by Richardson of Keith’s visit to Lynn, Massachusetts, where, in broad Scotch, he called upon the quakers ‘in the queen’s name’ to return to ‘good old mother church.’ His mission, which barely lasted two years and a half, was signally successful, especially in Maryland, and with presbyterians even more than with quakers. He returned to England about the end of 1704; his age (about sixty-five) probably unfitting him for further travel. In February 1705 he appears as Wednesday morning lecturer at All Hallows, Lombard Street.

The bibliography of Keith’s publications fills twenty-three pages of Smith’s catalogue; six more are given to the Keithian controversy. Valuable, as precursors of Barclay’s Apology, are: 1. Immediate Revelation, &c., 1668, 4to; and 2. The Universall Free Grace of the Gospell, &c. [Amsterdam], 1671, 4to. Perhaps the ablest specimen of his mere polemics, accentuated by a galling title, is 3. The Deism of William Penn and his Brethren, 1699, 8vo. Keith’s criticism of the Apology, and account of his share in its workmanship, is in his powerful book, 4. The Standard of the Quakers examined, &c., 1702, 8vo. His own account of his missionary labours is in 5. A Journal of Travels, &c., 1706, 4to. In almost his last publication he returned to the mathematical studies of his youth, proposing a new method for ascertaining the longitude, in 6. ‘Geography and Navigation Compleated,’ &c., 1709, 4to. Keith’s variety of attainment and his controversial capacity are admitted by his opponents. His examination of quakerism is much more searching than that of later seceders, such as Isaac Crewdson; and he has more insight into the consequences of his own principles than is shown by recent reconstructors of quakerism, such as Joseph John Gurney It is partly the fault of his self-assertive disposition that justice has hardly been done to the genuineness of his personal convictions and the consistency of his mental development. In his later publications he answers his earlier arguments, but throughout his literary and religious history there runs a thread of attachment to the exteriors of belief and practice, which, after his first enthusiasm, really determined his course.

Sources: Barclay’s Works (Truth Triumphant), 1692, pp. 570 sq.; Croese’s Historia Quakeriana, 1696, pp. 192 sq.; George Fox’s Journal, 1696, pp. 433 sq.; Leslie’s Snake in the Grass, 1698, pp. 209, 259; Bugg’s Pilgrim’s Progress from Quakerism to Christianity, 1700, pp. 82, 344; Sewel’s History of the Quakers, 1725, pp. 616 sq.; Burnet’s Own Time, 1734, ii. 248 sq.; Life of John Richardson, 1757, pp. 103 sq.; Wilson’s Dissenting Churches of London, 1808, i. 137 sq.; Jaffray’s Diary, 1833, pp. 241, 257, 328, 548 sq.; Smith’s Catalogue of Friends’ Books, 1867, ii. 18 sq.; Hunt’s Religious Thought in England, 1871, ii. 300 sq.; Theological Review, 1875, pp. 393 sq.; Barclay’s Inner Life of Religious Societies of the Commonwealth, 1876, pp. 375 sq.; Storrs Turner’s The Quakers, 1889, pp. 248 sq. (an excellent account, but blunders in making Keith a son-in-law of George Fox); many of Keith’s publications.

This post consists of the entry on George Keith published in Volume XXX of the original edition of the Dictionary of National Biography, edited by Sidney Lee and published by Smith, Elder & Co. in 1892. The author of the entry was The Revd. Alexander Gordon.

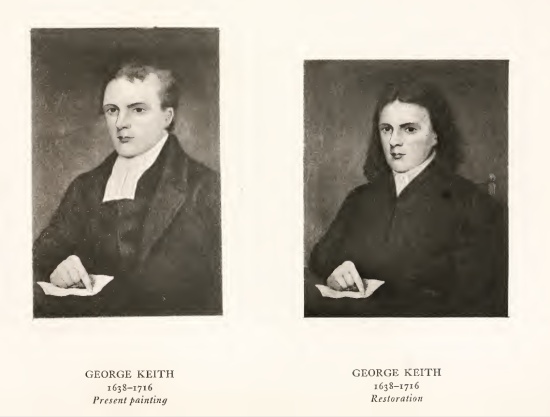

The portrait(s) of George Keith that appear(s) at the head of the post are taken from Charles Knowles Bolton (1919) The Founders: Portraits of Persons Born Abroad Who Came to the Colonies in North America Before the Year 1701, published by The Boston Athenaeum, Volume 1. Bolton comments (confusingly) as follows on page 6:

The portrait of George Keith has hung for years in the rooms of the Society for Propagating the Gospel, without question of its authenticity; but if it is genuine, Keith’s short hair and cut of coat would have outraged convention in his day. Evidently a painter ignorant of the period has retouched the canvas.

See also: