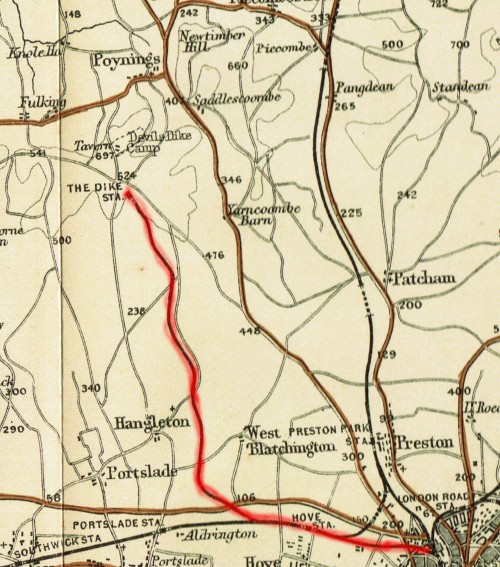

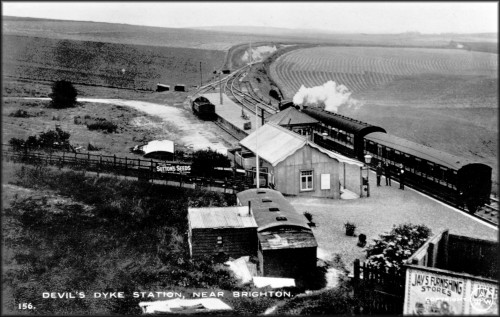

Plans for a railway to link Brighton to the Dyke were first mooted in the early 1870s but did not receive parliamentary approval until 1877. It took another decade before the railway was finally opened. In addition to the usual legal and property issues that attend the creation of a railway line, the overall gradient of 1 in 40 posed a significant technical challenge as did the hard chalk rock found at the end of the route. Indeed, the terminus of the line fell short of the Dyke by several hundred yards because the gradient at that point made further extension impractical.

Over the first year of operation, some 160,000 passengers were carried. The only intermediate stop at that time was at West Brighton (now Hove) Station. The total distance was 5.5 miles of which 3.5 were on the slope of the Downs. The trip took twenty minutes (just as the 77 bus from Brighton Station does today). The first additional intermediate stop to be added to the line was Golf Club Halt in 1891. This was a private platform built on what was then the property of Brighton & Hove Golf Club and provided for the use of its members. Two further intermediate stops opened in 1905, both on the main Brighton-Portsmouth line: Dyke Junction Halt (later renamed Aldrington Halt) and Holland Road Halt. The fourth, and final, addition was Rowan Halt built in 1933 to serve the new Aldrington Manor Estate that was then being developed to the north of the Old Shoreham Road.

The railway remained in operation for half a century with the exception of a closure of three and a half years at the end of WWI. When the line first opened in September 1887, there were eight trains a day (five on Sundays) between Brighton and the Dyke (and conversely). In June 1912, there were eleven trains a day (one fewer on Sundays). In November 1938, the penultimate month of operation, there were sixteen trains a day (half as many on Sundays). Conventional locomotives were used for most of the line’s life although a prototype steam railbus (essentially a large bus mounted on two bogies) was employed on the line in the mid-1930s and proved to be very popular with customers.

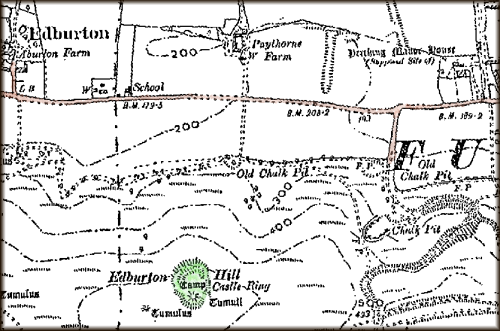

Although useful to members of the various golf clubs situated between Brighton and the Dyke, the primary passenger function of the railway was to take day trippers up to the Dyke in the morning and bring them back in the evening. Demand was thus seasonal and weather-dependent. Many of these visitors would use the Dyke as the basis for a day’s walking. Teashops sprang up in the villages at the foot of the Dyke to cater for their needs. Fulking and Saddlescombe each had one and Poynings had four at one stage. For those unwilling to stray off the Dyke itself, refreshments were also to be had at the Dyke Hotel and at Dennett’s Corner which was only a few yards from the station. A secondary passenger function was to take residents of Edburton, Fulking, Poynings, Saddlescombe and the various local farms into Brighton. The roads were poor and buses did not reach the Dyke until the 1930s. If you were not wealthy enough to have the use of a horse or, later, a car, then access to Brighton was difficult before the railway was built. Locals used the service to shop in Brighton and others commuted to work there.

Passengers were the main focus of the railway. But it also offered a goods service and this was economically important to the local villages. A goods siding was built at the Dyke Station in 1892. Coal, coke, cattle fodder and parcels were transported to the Dyke and collected from the station by horse and cart or by the local coal merchant. The latter then delivered both coal and parcels in the villages (and was paid a penny for each parcel by the railway company). On the return journey, goods wagons would take straw, hay, grain and local produce from the farms and market gardens into Brighton. Goods traffic was discontinued in January 1933.

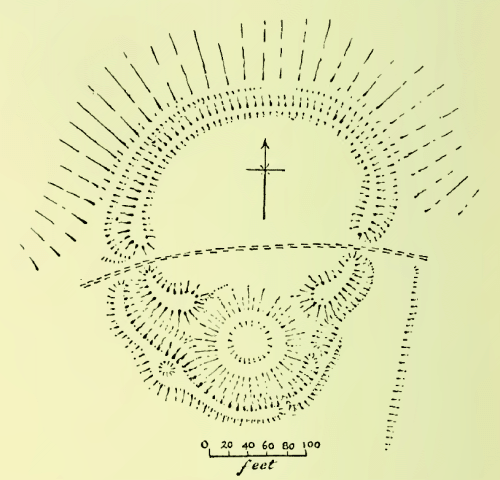

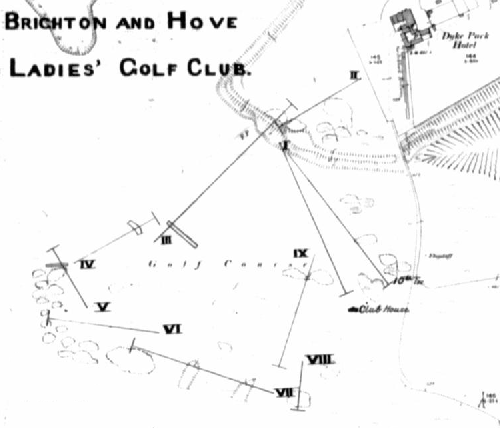

Golf Club Halt was a request stop rather than a real station. It never appeared in the rail timetables. However, the wishes of club members were reflected in the details of those timetables. There was a platform but that was all. You couldn’t buy a ticket for it — you had to purchase a ticket for the Dyke Station. If there were golfers on board, then the train would stop there to let them off. On the return journey, the train would stop to pick up golfers if they were visible on the platform (after dark, they struck matches). The platform was (and is) some fifty yards north of the clubhouse, perhaps because the gradient adjacent to the clubhouse made a more convenient location infeasible. However, from 1895 on, when a train was about to leave the Dyke Station, a bell would ring in the clubhouse alerting departing members to the need to make their way to the platform immediately. Although club members had mostly taken to using motor cars in the 1930s, the halt remained in use (especially when the weather was poor) until the railway itself was closed.

What remains of the railway today? South of the bypass, Brighton’s urban sprawl has eradicated almost every trace of it. Aldrington Halt remains in use, albeit unmanned. North of the bypass, the route is still visible either from the sky or on the ground, but you need to know what to look for. The cuttings and embankments that were needed to make the uphill route possible are there and dense scrub marks the location of the track for several long stretches. A public cycleway (the Dyke Railway Trail) running parallel to, or along, the track extends from the bypass to Brighton & Hove Golf Club. From then on, the line of the track runs through private farmland but a strip of scrub reveals its presence. Much of Golf Club Halt, which was never more than a platform, is still there, hidden in the scrub. At the northern terminus, Devil’s Dyke Farm now stands where Dyke Station once was. All that was left of the station a dozen years ago was a small chunk of the platform.

Further reading:

- Paul Clark (1976) The Railways of Devil’s Dyke, Sheffield: Turntable Publications. [This booklet contains a detailed history of all aspects of the line and includes maps, photos, transcripts of relevant documents, and engineering diagrams.]

- Peter A. Harding (2000) The Dyke Branch Line, Byfleet: Binfield Print & Design. [Reprinted in 2011, this well illustrated booklet is currently the most readily available work on the history of the railway.]

- Hove Borough Council (1989) Dyke Railway Trail [PDF], a four page leaflet. [The map contains a number of errors: e.g., both the exact railway route and Golf Club Halt are mislocated. Nevertheless, the leaflet is still useful if you plan a walk in the area.]

- Barry Hughes (2000) Brighton & Hove Golf Club: A History to the Year 2000. Brighton: B&HGC. [Pages 27, 30, 33, 42, 48, 60-61, and 115 contain material relevant to the railway and Golf Club Halt.]

Some other material relevant to the C19 and C20 history of the Dyke: