Tours of the 17th century Threshing Barn, Tudor Scullery and Donkey Wheel. You can also venture further afield for tours on surrounding Newtimber Hill. Refreshments at the Hiker’s Rest cafe. Children and dogs welcome. Parking £2 — follow signposts near Devil’s Dyke on the day. Sunday 13th September 2015, 10:30am–3:30pm, free admission.

Category: Local History

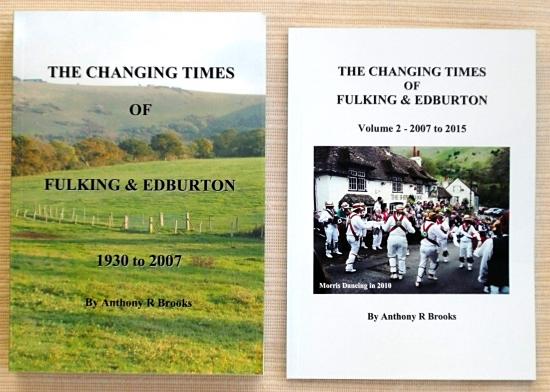

Tony Brooks, Volume 2 available now

Tony Brooks’s second volume of Fulking history has just been published and you can purchase a copy for £5.00. If you do not already have a copy of the first volume then you can buy both volumes for £16.00. Email hillbillybrooks@talktalk.net or call Tony on 200 to place your order.

St. Andrew’s Edburton

Today sees the continuation of our series of posts on the history of St. Andrew’s. You can read F.A. Howe’s 1949 essay on St. Katherine’s Chapel and its rather gruesome link to a popular firework; Lindsay Fleming’s 1958 article on the Hippisley Memorial, whose restoration he supervised, and the wording of the no longer legible verse that appears on it; and the results of Chris Comber’s recent work on the identities of those former residents of Fulking and Edburton whose names appear on one or both of the two War Memorials.

Today sees the continuation of our series of posts on the history of St. Andrew’s. You can read F.A. Howe’s 1949 essay on St. Katherine’s Chapel and its rather gruesome link to a popular firework; Lindsay Fleming’s 1958 article on the Hippisley Memorial, whose restoration he supervised, and the wording of the no longer legible verse that appears on it; and the results of Chris Comber’s recent work on the identities of those former residents of Fulking and Edburton whose names appear on one or both of the two War Memorials.

St. Andrew’s: St. Katherine’s Chapel

The north chapel of Edburton church, whose entrance arch groups so beautifully with the chancel arch and breaks the monotony of the long north wall of the nave, is a century or more later in date than the main building and is dedicated to St. Katherine of Alexandria.

We owe its existence to the family of de Northo who were established in the parish in the centuries after the Conquest. It was William de Northo who, in 1292, with his wife Olive, purchased lands in Edburton and neighbouring parishes, and again in 1325 when he purchased land from Robert de Frankeleyne, parson of Edburton, and another. Part of his wealth he devoted to building and endowing the chapel, for by a deed made at Bramber on 13th July 1319, he founded a chantry in the church and endowed it with one messuage, one virgate of land and fifty shillings of rent in the parishes of Edburton, Southwick, New Shoreham and Woodmancote, to provide a priest to pray for the souls of the “aforesaid William de Northo, his late wife Olive, and his present wife Christina, and all his ancestors”.

But why St. Katherine? The date of the founding of the chantry chapel gives the answer. The Crusades had opened communications with the near East, and the Eastern Church and its saints were acquiring a new interest in the West. There had grown up a great cult of St. Katherine of Alexandria virgin and martyr. Numerous churches were dedicated in her honour and her feast was kept with great solemnity. It will be remembered that she was one of St. Joan of Arc’s “voices”. The story is well known of her persecution as a Christian in which the attempt to martyr her on a spiked “catherine wheel” failed because it miraculously burst asunder. She is reputed to have been born about 310AD and by her learning is said to have confounded pagan philosophers, so that she came to be regarded as the patron saint of Christian philosophers. It is now admitted, however, that it is impossible to produce confirmatory evidence of the legends of her life and martyrdom (by beheading).

to Mount Sinai following her beheading.

F. A. Howe.

[This note was originally published in St. Andrews Quarterly 4, pages 21-22 (1949).]

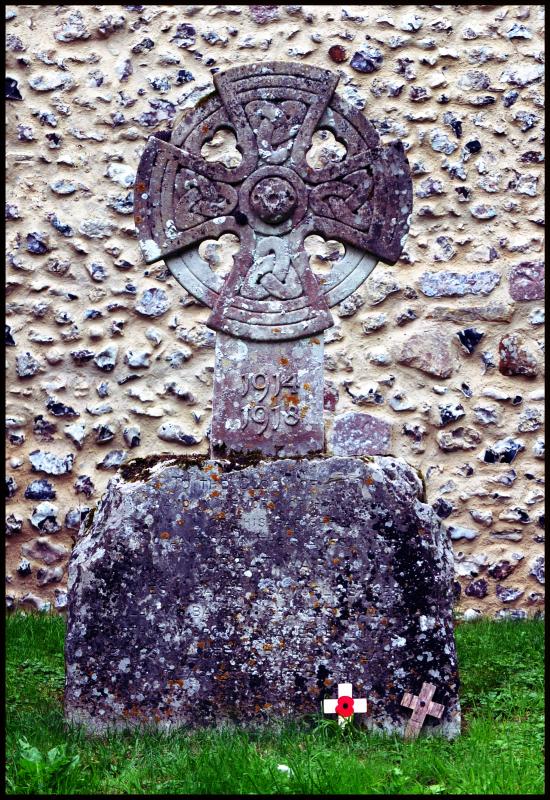

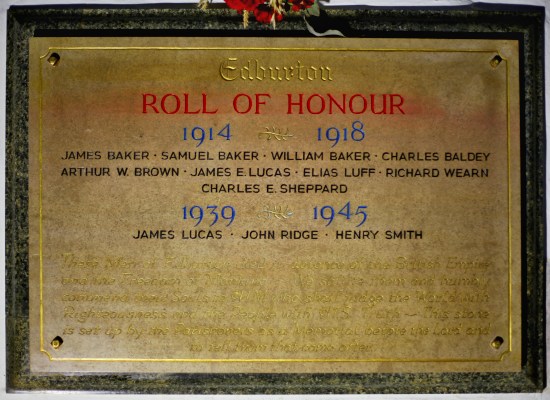

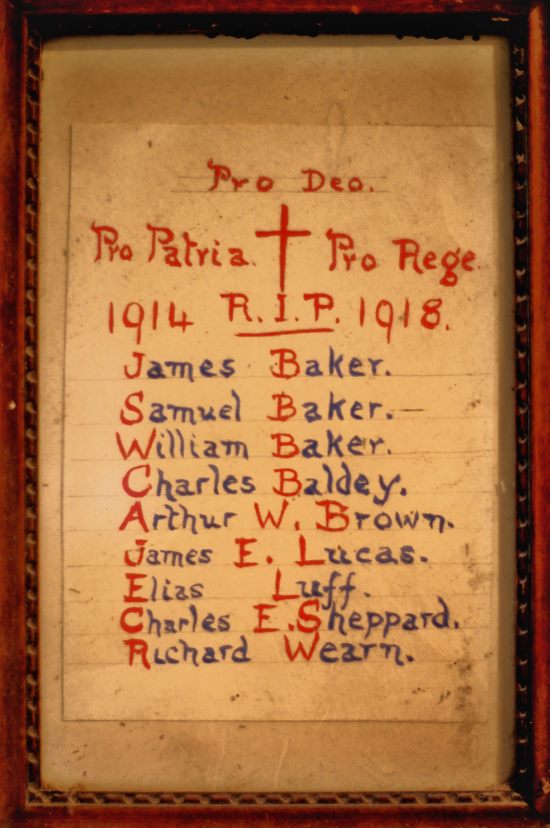

St. Andrew’s: The War Memorials

Inscription: 1914-1918 To the Glory of God and to the memory of the men of this parish who laid down their lives in the great war.

1914-1918

- James Baker

- Private G/12944, 1st Battalion, The East Kent Regiment, 6th Division. Killed in action 10th December 1916. Aged 26. Husband of Annie Edith Baker (née Hedger) of Edburton (remarried Backshall); later of The Old School House, Nep Town, Henfield. Born in Hangleton and enlisted in Henfield. Formerly with The 1/4th Royal Sussex. Buried in Guards Cemetery, Windy Corner, Cuinchy, F.279.

Began work as a farm carter boy, married in Brighton in the year he died, resident at School Cottages, Edburton. Served successively in Greece, Turkey, Egypt and France. Awarded the 1914-15 Star and the British War and Victory Medals. Died in Pas de Calais.

- Samuel Baker

- Private G/16288, 12th Battalion, The Royal Sussex Regiment, 39th Division. Killed in action on the Somme 22nd October 1916. Husband of Mrs. S. Baker of Stables Cottage, Albourne. Born in Hangleton in 1890 and enlisted in Worthing. Buried in Connaught Cemetery, F.215.

Awarded the British War and the Victory Medals. Brother of James (above) and William (below).

- William Baker

- Not positively identified, but possibly (i) William Baker, Private L/8948, 1st Battalion, Royal Sussex Regiment. Died in Mesopotamia, 10th October 1916;

or (ii) William Baker, Private S/2066, 2nd Battalion, Royal Sussex Regiment. Killed in action at Richebourg, 9th May 1915. Both were awarded the 1914-15 Star and the British War and Victory Medals.Born in Portslade in 1879, the son of a farm carter. Subsequently lived in Shoreham, employed as farm labourer, beach carter and cartage contractor. Married Emily Grinstead in 1896. Of the four Baker brothers, only the youngest, Albert, survived the war.

- Charles Baldey

- Corporal 39955, 1/21st Battalion, The London Regiment (The Surrey Rifles), 63rd Division. Killed in action 25th August 1918. Aged 21. Son of Charles & Maria Baldey of High Croft, Nep Town, Henfield. Formerly with the Royal Sussex Regiment. Born in Brighton in 1898. Enlisted in Chichester. Resident of Fulking. Commemorated on The Vis en Artois Memorial, MR.16.

Awarded the British War and Victory Medals. The census records that his parents were running the Shepherd and Dog by 1901 and were still there in 1911. His father died in the same year as his son.

- Arthur William Brown

- Private SD/4950, 11th Battalion, The Royal Sussex Regiment, 39th Division. Killed in action on the Rue du Bois, Fleurbaix, 30th June 1916. Aged 33. Son of James Arthur & Mary Anne Brown of Edburton. Born in Westmeston and enlisted in Brighton. Buried in St. Vaast Post Military Cemetery, F.631.

Farm labourer. Awarded the British War and the Victory Medals.

- James Edward Lucas

- Private G/9194, 2nd Battalion, The Royal Sussex Regiment, 1st Division. Killed in action near Bazentin, 7th August 1916. Aged 23. Son of Obadiah & Rhoda Lucas of Fulking, uncle of James Lucas (below). Born in Fulking and enlisted in Hove. Buried in Brewery Orchard Cemetery, F.83.

Grocer. Awarded the British War and the Victory Medals.

- Elias Luff

- Lance-Corporal L/4705, 10th Company, 3rd Home Reserve Battalion, The Royal Sussex Regiment. Died in Newhaven Military Hospital 18th April 1916 (Sussex Daily News). Aged 39. Son of Mr. Luff & Mrs. Susan Luff of Fulking. Old regular soldier recalled to the colours in 1914. Buried in Portslade Cemetery.

For a fuller account of what is known about the life and death of Private Luff, see Nightingale & Wilson-Wheeler (2016), pages 55-57.

- Charles Edward Sheppard

- Shoeing Smith 123947, C Battery, 187th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery. Died of wounds in Belgium, 6th October 1918. Aged 26. Husband of Mrs. Frances Sarah Florence Sheppard (née Franks) of Shaves Wood Farm, Albourne. Born in Fulking and enlisted in Hove. Buried in Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery, Belgium, B.11.

A general labourer, born in Fulking, enlisted in Hove, married in Edburton in 1917. Awarded the British War and Victory Medals.

- Richard Wearn

- Private 2040, 4th Battalion, The Australian Infantry. 1st Australian Division. Killed in action 15th May 1916. Aged 26. Son of William & Mary Wearn [Wearin] of Fulking. Buried in Merville Communal Cemetery, F.345.

A builder’s carter, born in Hove in 1889 and living with his parents in Kent Cottage in 1911, he emigrated to Australia the following year and became a gardener. He enlisted in the Australian Army in 1915, was wounded at Gallipoli and again, fatally, in France. Awarded the 1914-15 Star and the British War and Victory Medals.

Inscription: These Men of Edburton died in defence of the British Empire and the Freedom of Mankind ~ We salute them and humbly commend their Souls to HIM who shall judge the World with Righteousness and the People with HIS Truth ~ This stone is set up by the Parishoners as a Memorial before the Lord and to tell them that come after.

1939-1945

- James Lucas

- Flight Sergeant 751653, 55 Squadron, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve (Bristol Blenheim Mk.1Vs). Killed in action 12th September 1941. Age 20. Son of Percival Walter & Jane Mabel Lucas of Fulking, nephew of James Edward Lucas (above). Commemorated on the Alamein Memorial, Egypt.

- John Ridge

- Chief Officer, SS Punta Gorda (London), Merchant Navy. Died 18th September 1944. Aged 46. Husband of Mrs. Jane Elsie Ridge (née Cook) of Stammers Hill, Fulking. Commemorated on The Tower Hill Memorial, London.

Born in Woolwich, married in Steyning in 1924, buried in Aruba. Died as a result of a collision at sea. Awarded the 1939-1945 Star, the Atlantic Star, and the 1939-1945 War Medal.

- Henry Smith

- Not identified: one of 412 in CWGC records with that name.

Acknowledgements

The original text of the individual entries provided above is the work of Chris Comber and is taken from the relevant page of the invaluable Roll of Honour website, copyright © Roll-of-Honour.com, 2002-2015. We are very grateful to Chris Comber and Martin Edwards for their permission to use this material here.

Additional information concerning those who died in WWI has been abstracted from the relevant pages of Pat Nightingale & Ken Wilson-Wheeler (2016) The People of Beeding and Bramber in the Great War, Upper Beeding: Beeding & Bramber Local History Society. The same authors provided the linked Sussex Daily News clipping concerning the unusual circumstances surrounding the death of Lance-Corporal Elias Luff.

Finally, thanks to Ken Wilson-Wheeler for providing extra information about Chief Officer John Ridge.

Updated: 1st October 2015.

Revised and augmented: 20th February 2017.

Currently popular local history posts:

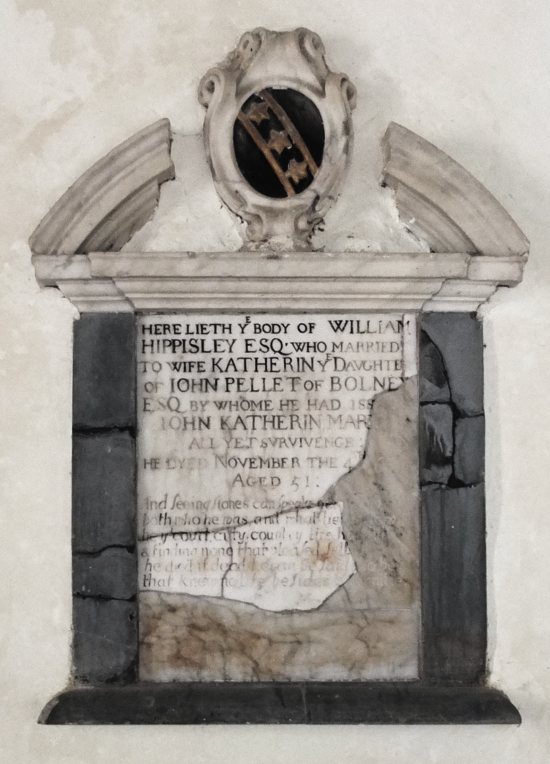

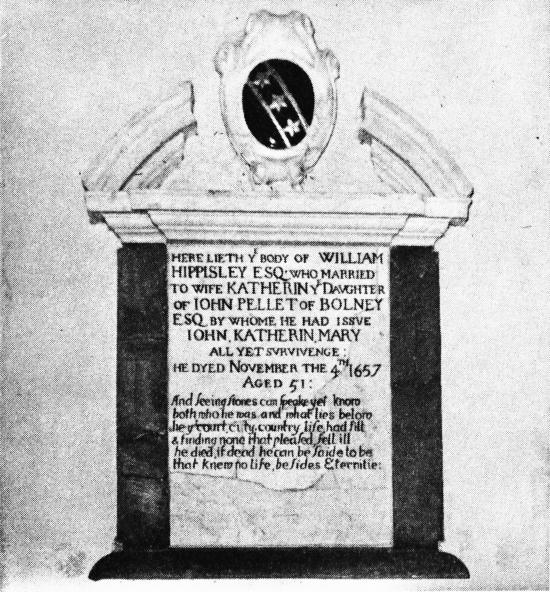

St. Andrew’s: The Hippisley Memorial

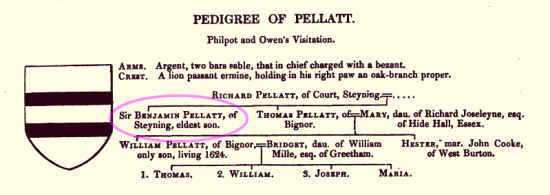

William Hippisley, who died aged 51 in 1657, married Catharine, co-heir to her grandfather Sir Benjamin Pellatt; from him she inherited Truleigh, in Edburton, Sussex. They had a son John and daughters Catharine and Mary. From the elder daughter descended the poet William Cowper. His mother was Anne Donne, whose mother was Catherine Clench, daughter of Catharine Hippisley.

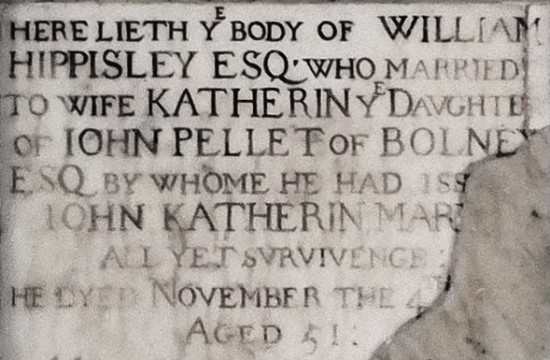

In the north transept of Edburton church William de Northo founded a chantry, in 1319. The Northo chapel later became known as the Truleigh Chapel and here was erected, perhaps some years after his death, a mural tablet to the memory of William Hippisley, above, it is presumed, the ledger stone that had already been laid in the north-east corner of the chapel. The ledger stone is inscribed:

Here Lieth the body of William Hippisley Esq who departed this life

the 4th day of November 1657 in the one and fiftieth yeare of his Age

As early as 1777 the inscription on the mural tablet had suffered the damage apparent today. In June of that year the Reverend Charles Vaughan Baker, Rector of Edburton 1754-1784, supplied particulars of the memorial to William Burrell, that the latter recorded in his manuscripts preserved in the British Museum (Add.Mss. 5698). It was on the north wall of the ‘Truly Chancel’ there was the coat-of-arms, and the imperfect inscription. At a date unknown the monument fell or was removed from the wall.

One learns (Sussex Archaeological Collections XXXII (1882), page 230) that the tablet, previously lying in fragments, had, in the course of the restoration of the church at the time, been re-fixed in the Truleigh Chapel. At a subsequent date, but not within the memory of any present parishioner [in 1958], the memorial was again removed and, until lately, lay in pieces at the west end of the nave.

| Here lieth ye body of William Hippisley Esq who married to wife Katherin ye daughter of John Pellet of Bolney Esq by whome he had issue John, Katherin, Mary all yet survivenge: he dyed November the 4th 1657 aged 51. |

The tablet is of white marble, now made good with composition, and is in a simple white and grey marble architectural frame, still nearly as far as can be judged complete; between the white marble broken pediment is a plain cartouche with coat-of-arms, as described in Sussex Archaeological Collections LXXII, pages 221-222; ‘Sable three rowels between two bendlets or’, for Hippesley. The missing words of the inscription have been conjecturally added, with the aid of hints from Sussex Archaeological Collections XXXIV (1886), pages 261-262, but in a way to distinguish from the surviving original inscription. In the following transcript the lost words or part words are shown in italics:

And seeing Stones can speake yet show

Both who he was and what lies below

He that Court, City, Country Life had fill

And finding none that pleased fell ill.

He died, if dead he can be saide to be

That knew no life besides Eternitie.

There are notices and pedigrees of the Pellatt family, with reference to William Hippersley or Hippesley, so spelt [in] Sussex Archaeological Collections XXXVIII, page 121 and opposite page 112, and in Elwes & Robinson Castles, Mansions and Manors of Western Sussex, part I, page 86 and opposite page 34. Of Hippisley I can find nothing, other than in the authorities I have mentioned. He may have been kin to the family of the name, of Yatton in Somerset, or to the family of whom there are memorials in the church of Lambourn, Berkshire (D. & S. Lysons Magna Britannica volume I, part II, page 309).

The Hippisley Memorial [is] an attractive feature of Edburton church, if not an imposing one, interesting too, for the association with, in Hayley’s words, ‘that amiable man and charming author’, William Cowper. May William Hippisley have transmitted his melancholy and varied genius to his far-away descendant?

Lindsay Fleming FSA

The first half of this post comprises a very lightly edited version of an article that originally appeared in the January 1958 issue of St. Andrews Quarterly. The author was a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries and a prolific writer of scholarly books on local and ecclesiastical history. His first book was published when he was just 22. Later works included Memoir and select letters of Samuel Lysons, 1763-1819 (1934); Beechcroft. The Story of The Birkenhead Settlement 1914-1924 (1938) with Horace Fleming; History of Pagham in Sussex: Illustrating the administration of an archiepiscopal hundred, the decay of manorial organisation and the rise of a seaside resort (1949-50) in three volumes; The little churches of Chichester: St. Peter North Street, St. Olave North Street, St. Andrew Oxmarket, All Saints in the Pallant (1957); The Church of St. John Baptist, Westbourne, in the Diocese of Chichester, Sussex (1958); and The Chartulary of Boxgrove Priory (1960) translated from the Latin and edited by LF. The son of Peter Fleming, a wealthy antiquarian and rare book collector who lived at Aldwick Grange in Bognor Regis, Lindsay Fleming retained the family home after the death of his father (c1933) and died there himself in 1966 at the age of 64.

Lindsay Fleming’s article was prefaced by some background remarks, probably written by the then-Rector F.J. Cornish, that are themselves worthy of note and are thus reproduced below:

For very many years the Hippisley Memorial has lain in fragments in the Nave of St. Andrews Church, Edburton, and recently Mr. Lindsay Fleming very kindly wrote to the Rector, Reverend F.J. Cornish, suggesting that a memorial of such interest would be better if repaired (where possible) and re-sited and fixed in the wall of the church.

After consultation with Mr. Francis W. Steer who is the County Archivist, the Rector, the Honorary Secretary of the Parochial Church Council and Mr. L. Anscombe, the monumental mason, it has been agreed that this work be done.

Very many people, including visitors to the Church, have sought more information of the Memorial than given in the little pamphlet dealing with the history of St. Andrews Church, so we are happy to print a much fuller report, prepared by Mr. Lindsay Fleming himself.

It may be some little time before the Memorial is refixed, but due mention will be made in the Quarterly.

In the event it seems that the necessary work was done rather quickly since F.A. Howe was able to insert an addendum to the end of the table of contents for his 1958 book (A Chronicle of Edburton and Fulking in the County of Sussex. Crawley: Hubners Ltd.) as the book went to press as well as a photograph of the restored memorial (ibid., page 102). Both are reproduced below:

ADDENDUM Since the book went to press the monument has been reassembled and repaired under the guidance of Mr. Lindsay Fleming FSA, and Mr. F.W. Steer FSA, and is now affixed to the north-west wall of the nave. A conjectural completion of the broken lines of the verse has been added:

The Hippisley MonumentAnd seeing stones can speake yet know

Both who he was and what lies below

He yt court, city, country life had fill

And finding none that pleased, fell ill

He died, if dead he can be saide to be

That knew no life, besides Eternitie

Apart from additional commas and the abbreviation of ‘that’ as ‘yt‘, the only change from Fleming’s conjectured verse is the replacement of ‘show’ with ‘know’ in the first line.

Howe’s book contains a couple of shards of additional information about William Hippisley: a reference to him as ‘WH of Hurstpierpoint’ (page 13) and a note of his summons to appear before the Quarter Sessions in early April 1649 — a couple of months after the execution of Charles I — for “divers seditious words and speeches” (page 21).

The Reverend C.H. Wilkie seems to have made something of a hobby of the memorial during his time as Rector of Edburton (1877-1884) including corresponding with members of the Hippisley family. He discovered that:

William Hippisley was educated at Westminster, and became Fellow of Christ Church, Oxford. He travelled with the Duke of Buckingham as his tutor. He was nephew to Sir John Hippisley, of the Long Parliament.

Sussex Archaeological Collections XXXV (1887), page 196.

Circa 1550 perhaps?

On the market

Rectors of Edburton

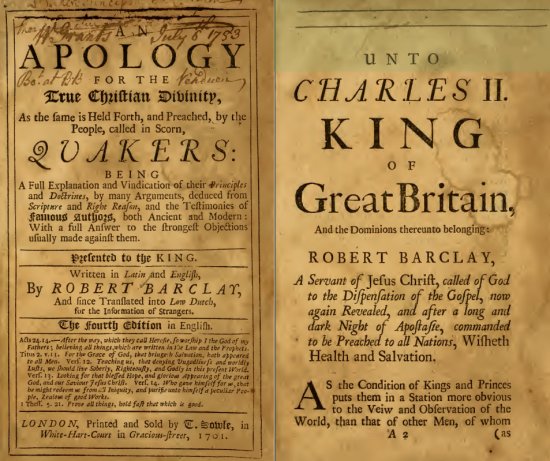

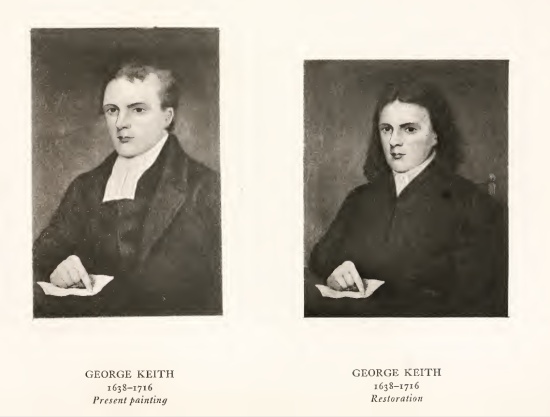

The first four posts in an occasional series on the rectors of Edburton appear in our local history section today. All four posts concern George Keith (c1639-1716) who, amongst distinguished company, is probably the best known of all our rectors. Certainly he is the one about whom most has been written. He was a quite remarkable man: author, colonist, jailbird, mathematician, missionary, polemicist, preacher, quaker, schoolmaster, surveyor, theologian and, finally, an unappreciated Anglican priest in the middle of nowhere.

The first four posts in an occasional series on the rectors of Edburton appear in our local history section today. All four posts concern George Keith (c1639-1716) who, amongst distinguished company, is probably the best known of all our rectors. Certainly he is the one about whom most has been written. He was a quite remarkable man: author, colonist, jailbird, mathematician, missionary, polemicist, preacher, quaker, schoolmaster, surveyor, theologian and, finally, an unappreciated Anglican priest in the middle of nowhere.

George Keith [Alexander Gordon, 1892]

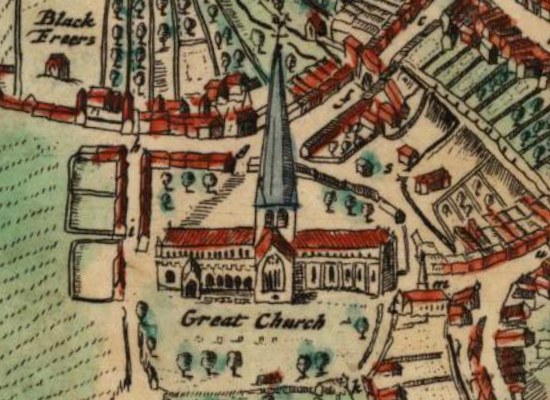

George Keith (1639?–1716), ‘Christian quaker’ and Anglican missionary, was born about 1639 in Scotland, probably in Aberdeenshire, but not at Aberdeen (Barclay, Truth Triumphant, 1692, p. 588). Educated at Marischal College, Aberdeen, where he graduated M.A., he was a class-fellow of Gilbert Burnet in the period 1653–7. He was a good mathematician, and an oriental scholar. On leaving college he became tutor and chaplain in a noble family. Designed for the presbyterian ministry, but apparently not ordained, he adopted the tenets of the quakers, first promulgated in the Aberdeenshire district towards the end of 1662 by William Dewsbury There is nothing to show how he was drawn to quakerism; the date of his ‘conviction’ is almost coincident with the restoration of episcopacy in the Aberdeen diocese. In 1664 he went on a mission to quakers at Aberdeen, and was imprisoned for ten months in the tolbooth. Nevertheless in 1665 he attempted to address the assembled congregation at ‘the great place of worship,’ probably St. Nicholas’s Church, Aberdeen, when he was knocked down by the bell-ringer. For preaching in the graveyard at Old Deer, Aberdeenshire, he was locked in the ‘thieves-hole,’ a windowless dungeon. In 1669 he was a prisoner in the tolbooth at Edinburgh.

After the adhesion of Robert Barclay (1648–1690) to quaker principles in 1667, Keith exercised an important influence in shaping the phraseology of the future apologist, and providing him with illustrative materials for his great work. Even the substance of Barclay’s doctrine shows traces of the christology of Keith, who had adopted from Postel the idea of a strong distinction between the celestial and the earthly Christ. Keith was probably the author of the English translation (1674) of Pocock’s ‘Philosophus Autodidactus,’ from which he supplied Barclay with the story of Hai Ebn Yokdan (Apology, prop. v. vi. § 27). On 14 Feb. 1675 he took part with Barclay at an open-air discussion ‘in Alexander Harper his close,’ Aberdeen, when Barclay’s ‘theses,’ the substratum of his Apology, were defended against a number of divinity students. Two short treatises of this period, ‘Quakerism No Popery,’ a reply to John Menzies’s ‘Roma Mendax’ (1675) and ‘Quakerism Confirmed’ (1676), were the joint work of Barclay and Keith. At the end of 1676 the latter was again imprisoned, with Barclay and others, in ‘the chapel,’ or lower prison, of Aberdeen.

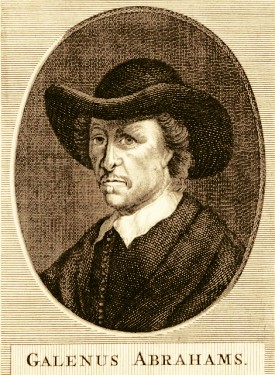

Keith was anxious to secure the doctrinal unity of the quaker movement, by means of a joint confession of faith, an idea which evidently did not commend itself to George Fox (1624–1691). Barclay and the Keiths joined Fox, Penn, and others in an expedition to Holland, sailing from Harwich on 25 July, and reaching Rotterdam on 28 July. Here they remained to superintend some printing, rejoining Fox for the ‘quarterly meeting’ at Amsterdam on 2 Aug. The establishment of a ‘yearly meeting’ for Germany followed, and on 6 Aug. Keith, Barclay, and Penn set out on a missionary tour, with Benjamin Furly as interpreter. Barclay soon returned to England with Elizabeth Keith. Keith and Penn pushed on to Heidelberg. On their return to Amsterdam they held a discussion with Galenus Abrahams, a Mennonite teacher of Socinian leanings. They embarked for Harwich with Fox on 21 Oct.

Keith was anxious to secure the doctrinal unity of the quaker movement, by means of a joint confession of faith, an idea which evidently did not commend itself to George Fox (1624–1691). Barclay and the Keiths joined Fox, Penn, and others in an expedition to Holland, sailing from Harwich on 25 July, and reaching Rotterdam on 28 July. Here they remained to superintend some printing, rejoining Fox for the ‘quarterly meeting’ at Amsterdam on 2 Aug. The establishment of a ‘yearly meeting’ for Germany followed, and on 6 Aug. Keith, Barclay, and Penn set out on a missionary tour, with Benjamin Furly as interpreter. Barclay soon returned to England with Elizabeth Keith. Keith and Penn pushed on to Heidelberg. On their return to Amsterdam they held a discussion with Galenus Abrahams, a Mennonite teacher of Socinian leanings. They embarked for Harwich with Fox on 21 Oct.

It was probably on his way back to Scotland that Keith visited Anne Conway, viscountess Conway, at Ragley Hall, Warwickshire. She sent a contribution towards the building of a quaker meeting-house at Aberdeen, and from her physician, Francis Mercurius van Helmont, Keith derived a belief in the pre-existence and transmigration of souls. At an earlier stage in the quaker movement opinions not less erratic might have passed without challenge; but though Keith never obtruded his new position, defending it rather as providing an opportunity for the salvation of those unreached by Christ in a prior term of existence, it was regarded as a heresy.

About 1680 Keith started a boarding-school, first at Edmonton, Middlesex, then at Theobalds, Hertfordshire. For refusing to take the oath he was imprisoned in 1682. The apologist placed his eldest son, Robert Barclay, at his school in 1683. Next year Keith was again imprisoned in Newgate. Some four years later he emigrated to America, settling at Philadelphia in 1689 as schoolmaster.

This migration was the turning-point in Keith’s career. Sewel connects his alienation from the quakers with condemnatory expressions, harsher than he could brook, directed by certain individuals against his doctrine of transmigration. But in a publication at Philadelphia in 1689 (‘The Presbyterian … Churches in New England … Brought to the Test,’ &c.) his allusions to a use of the Lord’s Supper (in the form of an agape), though not exceeding the liberty allowed in Barclay’s Apology (prop. xiii. §§ 8, 11), are significant of a tendency of his mind which brought him out of harmony with quaker modes of thought. On other points, denying the sufficiency of the inner light, he inclined to a stronger assertion of historic and dogmatic Christianity than was palatable to some Philadelphia quakers. He made enemies of William Stockdale (d. 1693), a prominent elder from the north of Ireland, and Thomas Lloyd (d. 10 Sept. 1694), the deputy-governor. The deaths of Barclay and Fox, within a few months of each other, left no one (1691) in the quaker community to whom Keith was inclined to submit, and he aspired to a position of leadership.  The ‘yearly meeting’ at Philadelphia, in September 1691, upheld Keith against Stockdale, while blaming the angry spirit shown by both. Nevertheless in the ‘monthly meeting’ Thomas Fitzwalter, a quaker minister, arraigned as heresy Keith’s denial of the sufficiency of the light within. The peace of the community was seriously endangered; hence Lloyd and the magistrates intervened, with no goodwill to Keith. But it was clear that the majority of ministers and elders was on his side. Accordingly the magistrates gave judgment against Stockdale and Fitzwalter, suspending them from their functions till they had made public amends for their action against Keith. This they ultimately declined to do, but persisted in exercising their ministry, stigmatising their opponents as Keithians. From this point Mr. Joseph Smith, the quaker bibliographer, dates Keith’s ‘apostasy.’ Keith, who made no effort to exclude his opponents, confidently expected their return. Fearing the consequences of the rupture, the magistrates convened a special court of twenty-eight ministers and magistrates, including some who, like Lloyd, and Samuel Jenings, the leading spirit against Keith, held both functions. This court at its first sitting, on 20 June 1692, condemned Keith unheard, and interdicted him from preaching. Keith held his ground. Assisted by Thomas Budd he published a ‘Plea of the Innocent’ and other pamphlets, and maintained distinct meetings for worship, his followers denying that they were separatists. William Bradford, the printer of his ‘Appeal’ to the ‘yearly meeting,’ was sent to prison. Keith and his friends, calling themselves ‘Christian quakers,’ held their own ‘yearly meeting’ at Burlington on 7 Sept. Fresh adherents came to them from the Mennonite settlers in Pennsylvania. After various wrangles, a new court, presided over by Jenings, sat at Philadelphia from 9 to 12 Dec., when Keith and others were condemned in a fine (not exacted) for personalities against Lloyd, and for denying the magistrates’ right to arm the Indians in self-protection, and to employ hired force against privateers; a position which shows the influence of Mennonite tenets. To the same influence may be ascribed a collective ‘Exhortation & Caution to Friends against buying or keeping of Negroes,’ issued by the Keith party on 13 Oct. 1693, and apparently the earliest quaker protest against slavery.

The ‘yearly meeting’ at Philadelphia, in September 1691, upheld Keith against Stockdale, while blaming the angry spirit shown by both. Nevertheless in the ‘monthly meeting’ Thomas Fitzwalter, a quaker minister, arraigned as heresy Keith’s denial of the sufficiency of the light within. The peace of the community was seriously endangered; hence Lloyd and the magistrates intervened, with no goodwill to Keith. But it was clear that the majority of ministers and elders was on his side. Accordingly the magistrates gave judgment against Stockdale and Fitzwalter, suspending them from their functions till they had made public amends for their action against Keith. This they ultimately declined to do, but persisted in exercising their ministry, stigmatising their opponents as Keithians. From this point Mr. Joseph Smith, the quaker bibliographer, dates Keith’s ‘apostasy.’ Keith, who made no effort to exclude his opponents, confidently expected their return. Fearing the consequences of the rupture, the magistrates convened a special court of twenty-eight ministers and magistrates, including some who, like Lloyd, and Samuel Jenings, the leading spirit against Keith, held both functions. This court at its first sitting, on 20 June 1692, condemned Keith unheard, and interdicted him from preaching. Keith held his ground. Assisted by Thomas Budd he published a ‘Plea of the Innocent’ and other pamphlets, and maintained distinct meetings for worship, his followers denying that they were separatists. William Bradford, the printer of his ‘Appeal’ to the ‘yearly meeting,’ was sent to prison. Keith and his friends, calling themselves ‘Christian quakers,’ held their own ‘yearly meeting’ at Burlington on 7 Sept. Fresh adherents came to them from the Mennonite settlers in Pennsylvania. After various wrangles, a new court, presided over by Jenings, sat at Philadelphia from 9 to 12 Dec., when Keith and others were condemned in a fine (not exacted) for personalities against Lloyd, and for denying the magistrates’ right to arm the Indians in self-protection, and to employ hired force against privateers; a position which shows the influence of Mennonite tenets. To the same influence may be ascribed a collective ‘Exhortation & Caution to Friends against buying or keeping of Negroes,’ issued by the Keith party on 13 Oct. 1693, and apparently the earliest quaker protest against slavery.

The controversy reached London. To allay it an authorised statement of Christian doctrine, drawn up by George Whitehead, was issued in 1693; a shorter statement was presented to parliament in December of that year. The influence of Keith’s views is seen in the minutes of the Aberdeen ‘quarterly meeting,’ which record on 9 Sept. 1693 the establishment of ‘a consolatory repast (as among the primitive Christians) from house to house.’ Keith came to London in 1694, attending the ‘yearly meeting,’ which was held on 3 May and adjourned to 11 June, when fruitless efforts were made to end the division. At length, on 15 May 1695, Keith, till he should make public amends, was disowned by the ‘yearly meeting,’ not ‘for his doctrinal opinions, but for his unbearable temper and carriage’ (Barclay, Inner Life, p. 375), and for his refusal to withdraw his charges against Philadelphia quakers.

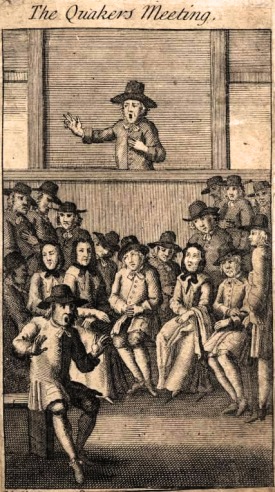

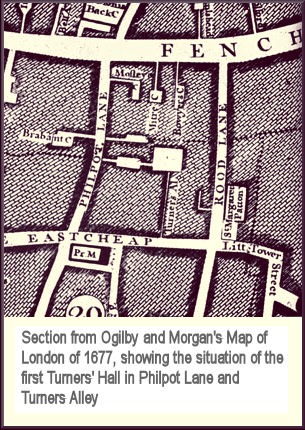

Keith, on his part, disowned the ‘yearly meeting.’  He obtained a meeting-house at Turners’ Hall, Philpot Lane, Fenchurch Street, which had been vacated by general baptists in June 1695. Here, while retaining the quaker name, garb, and speech, he administered baptism and the Lord’s Supper. His meeting-house was thronged; his sermons were continuous attacks upon the orthodoxy of quakers, especially of Penn, whom he accused of deism. From time to time he published ‘narratives’ of his proceedings at Turners’ Hall. In 1698 and 1699 he went on controversial tours among the quakers in the provinces. At Bristol, in August 1699, he was threatened with the law if he entered the meeting-house, though he promised to make no disturbance. On 5 May 1700 he preached a ‘farewell sermon’ at Turners’ Hall, giving his reasons for conforming to the established church. He was at once ordained by Henry Compton (1632–1713), bishop of London, and preached his first sermon as an Anglican clergyman on 12 May at St. George’s, Botolph Lane, Lower Thames Street. Sewel notes as remarkable that he sometimes preached in a surplice. He continued to make tours in order to denounce quakerism, visiting Bristol and Colchester in 1700 and 1701; he claims to have led five hundred quakers to conform. His last ‘narrative’ of proceedings at Turners’ Hall is dated 4 June 1701. His successor in the use of the meeting-house was Joseph Jacob.

He obtained a meeting-house at Turners’ Hall, Philpot Lane, Fenchurch Street, which had been vacated by general baptists in June 1695. Here, while retaining the quaker name, garb, and speech, he administered baptism and the Lord’s Supper. His meeting-house was thronged; his sermons were continuous attacks upon the orthodoxy of quakers, especially of Penn, whom he accused of deism. From time to time he published ‘narratives’ of his proceedings at Turners’ Hall. In 1698 and 1699 he went on controversial tours among the quakers in the provinces. At Bristol, in August 1699, he was threatened with the law if he entered the meeting-house, though he promised to make no disturbance. On 5 May 1700 he preached a ‘farewell sermon’ at Turners’ Hall, giving his reasons for conforming to the established church. He was at once ordained by Henry Compton (1632–1713), bishop of London, and preached his first sermon as an Anglican clergyman on 12 May at St. George’s, Botolph Lane, Lower Thames Street. Sewel notes as remarkable that he sometimes preached in a surplice. He continued to make tours in order to denounce quakerism, visiting Bristol and Colchester in 1700 and 1701; he claims to have led five hundred quakers to conform. His last ‘narrative’ of proceedings at Turners’ Hall is dated 4 June 1701. His successor in the use of the meeting-house was Joseph Jacob.

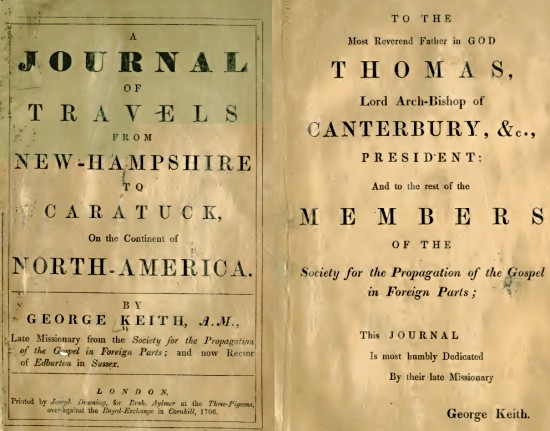

In 1702 Keith returned to America as one of the first missionaries sent out by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (incorporated 1701). A curious account is given by Richardson of Keith’s visit to Lynn, Massachusetts, where, in broad Scotch, he called upon the quakers ‘in the queen’s name’ to return to ‘good old mother church.’ His mission, which barely lasted two years and a half, was signally successful, especially in Maryland, and with presbyterians even more than with quakers. He returned to England about the end of 1704; his age (about sixty-five) probably unfitting him for further travel. In February 1705 he appears as Wednesday morning lecturer at All Hallows, Lombard Street.

The bibliography of Keith’s publications fills twenty-three pages of Smith’s catalogue; six more are given to the Keithian controversy. Valuable, as precursors of Barclay’s Apology, are: 1. Immediate Revelation, &c., 1668, 4to; and 2. The Universall Free Grace of the Gospell, &c. [Amsterdam], 1671, 4to. Perhaps the ablest specimen of his mere polemics, accentuated by a galling title, is 3. The Deism of William Penn and his Brethren, 1699, 8vo. Keith’s criticism of the Apology, and account of his share in its workmanship, is in his powerful book, 4. The Standard of the Quakers examined, &c., 1702, 8vo. His own account of his missionary labours is in 5. A Journal of Travels, &c., 1706, 4to. In almost his last publication he returned to the mathematical studies of his youth, proposing a new method for ascertaining the longitude, in 6. ‘Geography and Navigation Compleated,’ &c., 1709, 4to. Keith’s variety of attainment and his controversial capacity are admitted by his opponents. His examination of quakerism is much more searching than that of later seceders, such as Isaac Crewdson; and he has more insight into the consequences of his own principles than is shown by recent reconstructors of quakerism, such as Joseph John Gurney It is partly the fault of his self-assertive disposition that justice has hardly been done to the genuineness of his personal convictions and the consistency of his mental development. In his later publications he answers his earlier arguments, but throughout his literary and religious history there runs a thread of attachment to the exteriors of belief and practice, which, after his first enthusiasm, really determined his course.

Sources: Barclay’s Works (Truth Triumphant), 1692, pp. 570 sq.; Croese’s Historia Quakeriana, 1696, pp. 192 sq.; George Fox’s Journal, 1696, pp. 433 sq.; Leslie’s Snake in the Grass, 1698, pp. 209, 259; Bugg’s Pilgrim’s Progress from Quakerism to Christianity, 1700, pp. 82, 344; Sewel’s History of the Quakers, 1725, pp. 616 sq.; Burnet’s Own Time, 1734, ii. 248 sq.; Life of John Richardson, 1757, pp. 103 sq.; Wilson’s Dissenting Churches of London, 1808, i. 137 sq.; Jaffray’s Diary, 1833, pp. 241, 257, 328, 548 sq.; Smith’s Catalogue of Friends’ Books, 1867, ii. 18 sq.; Hunt’s Religious Thought in England, 1871, ii. 300 sq.; Theological Review, 1875, pp. 393 sq.; Barclay’s Inner Life of Religious Societies of the Commonwealth, 1876, pp. 375 sq.; Storrs Turner’s The Quakers, 1889, pp. 248 sq. (an excellent account, but blunders in making Keith a son-in-law of George Fox); many of Keith’s publications.

This post consists of the entry on George Keith published in Volume XXX of the original edition of the Dictionary of National Biography, edited by Sidney Lee and published by Smith, Elder & Co. in 1892. The author of the entry was The Revd. Alexander Gordon.

The portrait(s) of George Keith that appear(s) at the head of the post are taken from Charles Knowles Bolton (1919) The Founders: Portraits of Persons Born Abroad Who Came to the Colonies in North America Before the Year 1701, published by The Boston Athenaeum, Volume 1. Bolton comments (confusingly) as follows on page 6:

The portrait of George Keith has hung for years in the rooms of the Society for Propagating the Gospel, without question of its authenticity; but if it is genuine, Keith’s short hair and cut of coat would have outraged convention in his day. Evidently a painter ignorant of the period has retouched the canvas.

See also: