On some Sunday just 246 years ago [i.e., in 1705] a little elderly parson ascended the pulpit of our church at Edburton for the first time and addressed his Sussex people in broad Scotch. He was George Keith, and he had travelled a long and hard road to the comparative peace of Edburton rectory, where he was to live as a faithful parish priest until his death eleven years later. No doubt his fame had preceded him even to this Sussex village, then so remote, for he was indeed famous in the troubled religious life of those times.

Early life. George Keith was born a Scot, and we are told that he never lost his native accent. He was born at Peterhead in or about 1638, and at the age of sixteen he went up to the college which is now Aberdeen University, and in due course he graduated Master of Arts. He had become a very able mathematician and he began to earn his living as a surveyor. He was even more learned in theology and philosophy, and he could find no settled home in the presbyterian in community to which his family belonged. Through the long troubles of reformation and the civil war presbyterianism had had a very chequered career. Sometimes for the bishops, more often against them; its story may well explain Keith’s dislike for organised religion in any form. In short, he became a Quaker. Now the Quakers adhered to no doctrines, but asserted that every man was directed entirely by what they called “the Light within”, by which a loving God illuminated each man’s conscience. Pressed to its logical conclusion, this meant that all external aids and revelations were unnecessary, whether they were bishops and priests and sacraments, or even the Bible itself. It was on these lines that the great Quaker preachers like George Fox taught, and it was this sect that Keith joined.

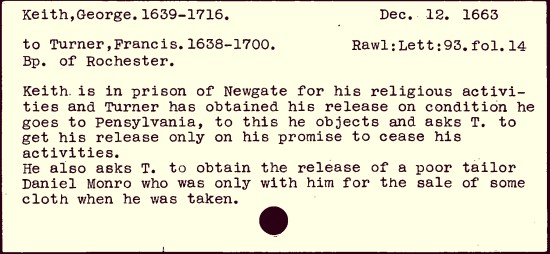

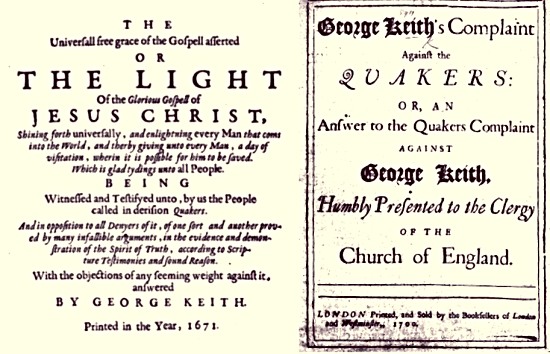

Keith was fearless. He well knew he was throwing in his lot with a persecuted body and, after the restoration of the monarchy, a still more persecuted body. It was not long before, for the first of many times, Keith found himself in prison. From the age of 25 to the age of 46 he alternated preaching among the Quakers in Aberdeen, London and Edinburgh with periods in prison for his refusal to conform to the established (Scottish) church, yet throughout this period we can perceive his growing dissatisfaction with the vagueness of the tenets of the Quakers. He published works, some of them written in prison, which, because they sought to settle more definitely certain doctrinal matters, caused disquiet among his Quaker brethren, so much so thet the Quaker bookseller in London was instructed not to sell them. He insisted on the need to supplement “the Light within” by reading the the Bible in order, as he wrote “to learn the more special heads and doctrines of the Christian faith”, and the most furious conflict of all raged round his insistence on the nature of Christ as God and Man, yet one Person, and so inevitably to the doctrine of the Holy Trinity. Already God was leading Keith towards the fine and complete faith of the Creeds.

America and the Quakers. In those seventeenth century days the idea of religious toleration was little understood, and when, after so many imprisonments for being a Quaker, Keith found himself imprisoned for the fourth time in three years, and this time for two years spent partly in Newgate on the fresh charge of conducting a school near London without the bishop’s licence, it is not surprising that his eyes turned towards America, whither so many, from the Pilgrim Fathers onwards, had gone before him to find religious freedom. Hundreds of Quakers were emigrating to the quaker colonies of East Jersey and Pennsylvania, and in 1684, having been appointed surveyor general of the colony of East Jersey, Keith left England with his wife, his daughters Anne and Elizabeth and two servants. He was now 47 years old, and well-known among his co-religionists. He was respected as preacher and scholar, and the mathematical library he took with him was proclaimed as one of the great assets of the colony. In his professional capacity he mapped out a boundary line between Jersey and New York State which was eventually adopted. He was allotted one of the best houses. He owned 1,500 acres. In the religious sphere he was made a leader (“Friend of the Ministry”) among the Quakers.

These years of peace and prosperity were not many for him. If the doctrines of the Quakers in England were vague, they were even less defined in America, and Keith soon became anxious lest the young people should fall away from belief in the Incarnation of Our Lord and his work of Redemption. Let us sample this downright way of expressing himself. “Airy notionistsi” he wrote “who teach and profess faith in the Christ within, and the Light and Word, but either deny or slight His outward coming, and what He did and suffered for us in the flesh” were gaining strength and must be checked. From 1688 to 1690 he preached up and down the American colonies from Massachusetts to New Jersey emphasising doctrine and the Scriptures, and at last he drew up and published a Quaker catechism which the annual Quaker “meeting” denounced as “downing the Popery”.

Then came the Babbitt affair. Babbitt, one of the most daring of the large and thriving body of smugglers, stole a ship from the wharves at Philadelphia, and as sure was he that the Quakers would not use force, that he did not even take the vessel away at once, but went on ravaging the banks of the river. The magistrates took the only possible course. They armed a group of men to put down the pirates, but — and here’s the rub — the majority of the magistrates were Quakers, and it was against Quaker principles to use force. Keith attacked them for this and found himself hailed before the civil court for subverting the governors. The gulf between Keith and official quakerdom was widening, and in 1692 he and a band of followers broke away and formed a new body, calling themselves “Christian Quakers”, but known elsewhere on both sides of the Atlantic as the “Keithites”.

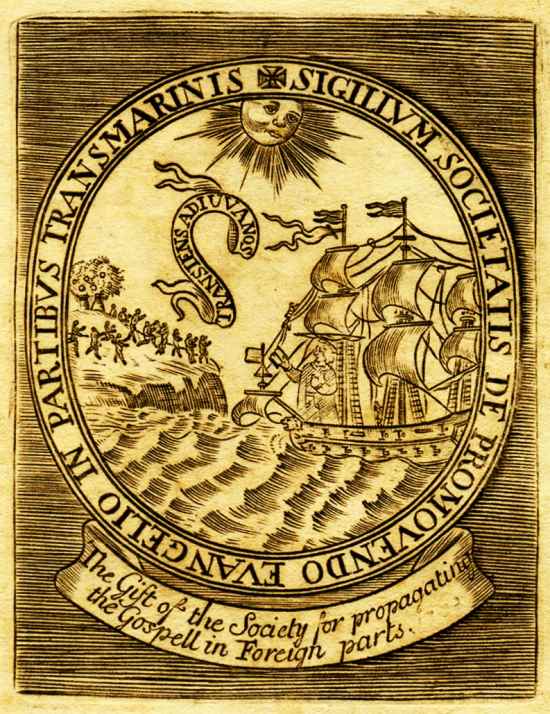

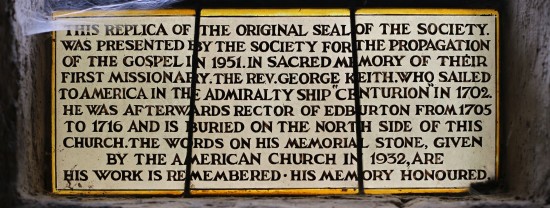

England and Conversion. In 1694 Keith came home, bringing his daughter Elizabeth back with him and his youngest daughter Margaret, wno had been born in America. His daughter Anne remained behind, having married a Quaker. In England, he found the Quakers no longer persecuted, but he also found his reception by them as unfriendly as the main body of Quakers in America. He preached through four countries to win back Quakers from their errors, and, more important, held regular meetings in London, which, because of Keith’s leaning towards orthodox doctrine, attracted clergy of the Church of England. All through the sixteen-nineties the dispute went on in the spoken and tne printed word. Keith’s attitude was not far removed from that of the established church, which founded the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge in 1699, and the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in 1701, each primarily to combat Quakerism and the false doctrine of God known as deism. While the S.P.G. was from the first a missionary body, the S.P.C.K. eagerly consulted Keith and distributed his writings. Keith felt severely his rejection by the Quakers. “An outcast, without the pale of organised religion, in an age when membership of a religious group was the accepted thing”, he was being driven “rapidly in the direction in which he had been travelling for many years” (says his principal biographer). So he came to enter the Church. He made his first communion in 1700, in 1701 he was made deacon and ordained priest in March 1702. He was 64 years old.

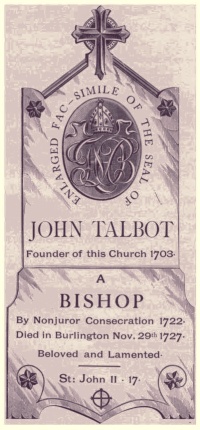

The Missionary Journey. The S.P.G. had already determined to send him on a missionary tour of the North American colonies, and on 28th April 1702, he embarked in the “Centurion” at Cowes. The most memorable of several distinguished fellow passengers was the Reverend John Talbot, the ship’s chaplain, who at the end of the voyage joined Keith in the missionary journey and became one of the most faithful priests of the church in America. The “Centurion” reached Boston on the 11th June, and Keith and Talbot lost no time in getting to work. On his very first Sunday ashore Keith preached to a large congregation in the Anglican Church in Boston on “The Doctrines of the Holy Apostles, Prophets and the foundation of the Church of Christ”. It was at once a proclamation of the definite position he had now reached as a priest of the church, and an attack on the Quaker doctrine of the Light within. It struck the key-note of his whole mission. He did not interrupt Quaker meetings, but made it a practice to attend and speak at the end. He went to a debate on freewill at Harvard University, and afterwards wrote a letter in Latin to the President of the University refuting the argument that “God has decreed not only Adam’s fall, but every sinful act since then”. He got no reply and thereupon printed and published the letter in English. So began another paper war, attacks on him pouring from the Quaker press, and the S.P.G. sending out lavish supplies of tracts teaching the orthodox religion.

betwixt Piscataway Kives in New England and Corretuck in North Carolina; of extent in length about 800 miles; within which bounds are ten distinct colonies and governments all under the Crown of England, viz., Piscataway, Boston, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, East and West Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia and North Carolina. I have travelled twice over most of these governments and colonies, and I preached oft in many of them, particular in Pennsylvania, West and East Jersey and New York provinces where we continued longest, and found the greatest occasion for our service .. To many our ministry was the sowing of seed, and planting, who never so much as heard one orthodox sermon preached to them before we came among them; who received the Word with joy, and of whom we have good hope that they will be as the good ground that bringeth forth fruit, some 30, some 60, some 100-fold. And to many others it was a watering to what had been formerly sown and planted among them; some of the good fruit thereof we did observe, to the glory of god and our great comfort while we were with them, even such fruits of true piety and good lives and sober and righteous living as prove the trees to be good from which they proceed.

Rector of Edburton. He returned to England in 1704 and landed at London on the 14th August. After a year spent in preaching, attending meetings of the S.P.C.K. and S.P.G. and writing his journal, he was presented by Archbistop Tenison to the Rectory of Edburton. He was now 67 years old.

Thomas Tenison, 1636-1715, became Archbishop of Canterbury in 1694. Noted for his ‘moderation towards dissenters’ and his sermon at the funeral of Nell Gwynne, Tenison was one of the founders of the S.P.G. and responsible for appointing Keith to Edburton.

Thomas Tenison, 1636-1715, became Archbishop of Canterbury in 1694. Noted for his ‘moderation towards dissenters’ and his sermon at the funeral of Nell Gwynne, Tenison was one of the founders of the S.P.G. and responsible for appointing Keith to Edburton.

We may wonder what, after a life of travel and turmoil, Keith thought of his new environment. We are accustomed to regard the Downs as the characteristic beauty of the Sussex landscape, but to the men of his day they appeared to them an ugly and depressing barrier. Even a century later than Keith this had not changed, for we find Dr. Johnson describing our British mountains as “Horrid protuberances”. Then, too, there were the notoriously bad Sussex roads. No coach came nearer than Steyning, and to Steyning Keith had to go, on horseback, to collect his letters, until later he became too ill to make even this journey.

A sketch map of Steyning from 1763: there wasn’t much to Steyning in those days and there was presumably even less half a century earlier when George Keith had to ride there to collect his mail.

A sketch map of Steyning from 1763: there wasn’t much to Steyning in those days and there was presumably even less half a century earlier when George Keith had to ride there to collect his mail.

He was still full of vigour when he came to Edburton, and he took up his campaign against the Quakers almost immediately by distributing anti-Quaker pamphlets provided by the S.P.C.K., and he enlisted the support of neighbouring clergy to help him in the distribution. In 1706 he challenged the Quakers to meet him at Lewes, but they did not respond. Then he went off on a summer tour of the country under the auspices of the S.P.C.K., getting as far afield as Falmouth, and later in the same year he intruded into the Quaker meeting at Steyning. His active co-operation with S.P.C.K. and S.P.G. went on at least until 1710, when there is a letter from him acknowledging a supply of pamphlets, and he had been at an S.P.C.K. conference the year before.

All the time he kept in touch with the missionaries in America, and 1707 was a memorable year when his old colleague of the missionary tour, John Talbot, came to England and visited him at Edburton.

All the time he kept in touch with the missionaries in America, and 1707 was a memorable year when his old colleague of the missionary tour, John Talbot, came to England and visited him at Edburton.

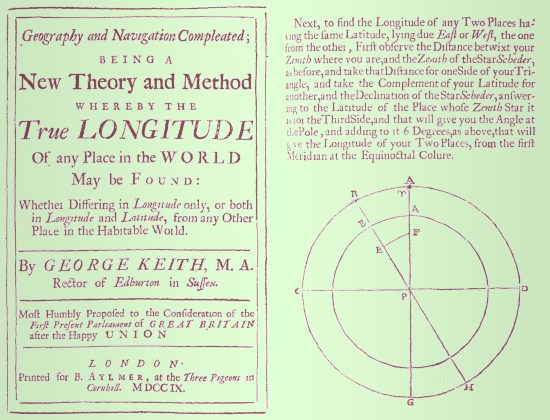

He even found time to produce a mathematical formula for calculating longitude in navigation.

In spite of all these extraneous activities, he was a faithful shepherd of his Edburton flock. He found the adults not very responsive, but the children were more amenable and he was able to write that, although there was no school, all could read and write and knew their Catechism. This could only have been by his patient and loving instruction. Baptisms, marriages and burials are recorded through the years in the church registers, with the affidavits required by law that the burials were in wool. A letter of his in 1710 throws light on his life at Edburton then:

Alas, there is none in this parish that would contribute in the least [to the charitable work of one of the Societies]. We have not one gentleman in the parish. We had one, but he and his family are gone to live at Chichester. The charge of the poor is so great upon the farmers, the parish being small, and the poor so many in it, that they have no inclination to contribute to any other charitable work.

Then he adds, very movingly, a reference to “the worthy Society, whose pious endeavours for the spreading of the knowledge of God and of his truth I daily pray Almighty God to bless and prosper still more and more”.

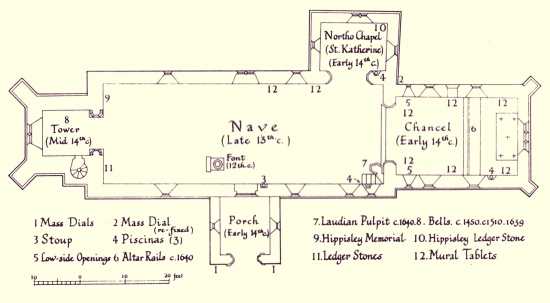

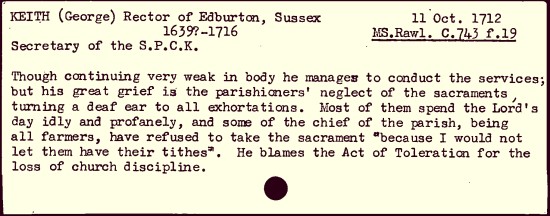

By this time his health was breaking, and the last six years of life were a brave fight against sickness. The rectory was “old and crazy”. Once he was ill in bed and the wall against which it stood gave way and tumbled into the garden, drawing the bed and its occupant half-way through the breach. By 1712, when he was 74 years old, he had to be carried to church, but nevertheless rejoiced that he could read the service and preach and administer the sacraments. The registers bear testimony to his struggle to carry on. From June 1711 to March 1712 the entries are not in his hand. Then his writing reappears, cramped and almost unreadable, but after 1713 another hand, probably his curate’s, enters the records. His last recorded act is the baptism of an infant in 1715. A year later he died, and the register closes the story: “29th March 1716. Then the Rev. Mr. Keith, Rector of Edburton was buried”.

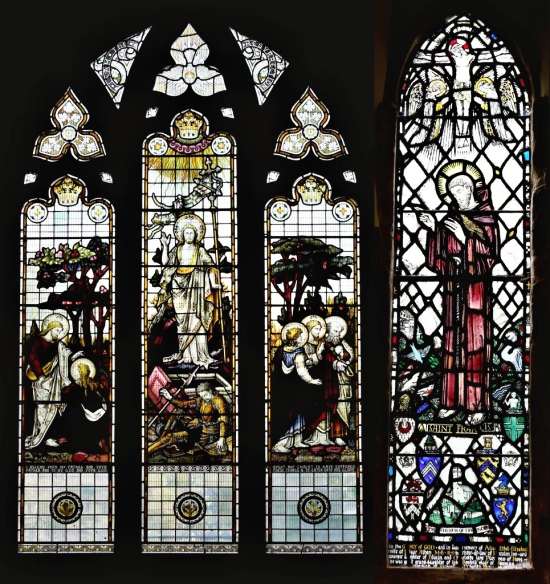

What shall be our estimate of this remarkable man? We shall surely be wrong if we dismiss him as one who rejoiced in quarreling with his Christian brethren. Rather should we take note of his untiring search for the truth, and his burning desire that those who, in his view, were in error should be brought to the truth. The age of religious tolerance in which he lived may appear strange to us, but dare we say that our present age of indifference to religion is more pleasing to Almighty God. To read the life of George Keith is to read the life of a fervent seeker after truth at all costs, and to trace the hand of God slowly leading him from the vaguest of faiths to the full revealed truth of God, to the unmatchable dignity of the Christian priesthood, and to the profession of the full faith of the Nicene Creed. An American writer (Hooper) concludes a short life of Keith:- “As controversialist, apostle, parish priest, George Keith deserved to be known and honoured in the church he loved so well; but above all must we regard him as Christ’s faithful soldier and servant unto life’s end”; His principal biographer, Dr. Ethyn Kirby, on whose work I have mainly drawn throughout, ends her book with the words: “His achievements .. cannot be overlooked in any history of Quakerism or Anglicanism both 1n America and England .. He was able to contribute greatly to the religious life of his day”. In the words inscribed on his tomb in the shadow of Edburton Downs “His work is remembered; his memory honoured”.

Main inscription: Sacred to the memory of the reverend George Keith missionary of the society for the Propagation of the Gospel to the American Colonies 1702-1704. This stone is placed here in the year 1932 by the Dioceses of the American Church which include the places he visited. Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Long Island, New York, New Jersey, Newark, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Southern Virginia, East Carolina. His work is remembered, His memory is honoured. Base inscription: Born at Aberdeen 1638. Rector of Edburton from the year 1705 to 1716. Died at Edburton 1716.

Main inscription: Sacred to the memory of the reverend George Keith missionary of the society for the Propagation of the Gospel to the American Colonies 1702-1704. This stone is placed here in the year 1932 by the Dioceses of the American Church which include the places he visited. Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Long Island, New York, New Jersey, Newark, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Southern Virginia, East Carolina. His work is remembered, His memory is honoured. Base inscription: Born at Aberdeen 1638. Rector of Edburton from the year 1705 to 1716. Died at Edburton 1716.

[This essay by F.A. Howe was first published in St. Andrew’s Quarterly No. 12 in October 1951.]

See also: