A page displaying a small set of maps describing the local geology has been added to the About Our Village menu in the left sidebar. Of necessity, the maps are large image files so attempting to look at them via a mobile phone is probably not sensible.

Category: Topography

The terrain, vegetation, architecture and artefacts of the area described by reference to location.

The manor of Perching

The four manors of Edburton, in common with others found along the South Downs, are oddly arranged to the modern eye. Together with Fulking*, they partition the parish into long thin irregularly shaped strips running from south to north. The explanation for this topography lies in the fact that the manors owed their existence to farming. Each manor was a self-contained mixed farming zone:

Each had its chunk of Down pasture, its rich malm and greensand arable under the Downs, its sticky wooded patch of gault clay beyond, and fertile lower greensand at the northern end. .. Each of the farmsteads had a daughter farm to the north on the lower greensand — Truleigh Sands, Edburton Sands, Nettledown, and Perching Sands. The woods of Tottington Longlands and Perching Hovel mark the poorly drained gault clay.

[Bangs 2008, page 216]

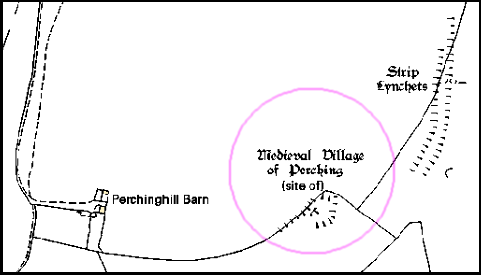

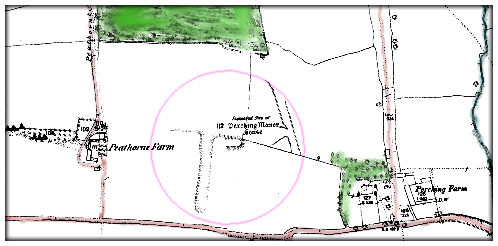

Sheep were grazed on the Downs, the northern escarpment provided chalk for lime and springs for a water supply, and the weald provided suitable land for crops, cattle, and rabbit warrens as well as woods providing timber and charcoal and a home for swine. In addition to the northern daughter farms listed by Bangs, at least some of the manors once had southern daughter farms located on the top of the Downs. Thus Paythorne had Summersdeane which had survived as a farm from Saxon times until Canadian tanks used it for target practice during WWII. In the case of Perching, the southern farm was probably located at the deserted medieval settlement to the east of the modern, but now dilapidated, Perching Hill Barn buildings.

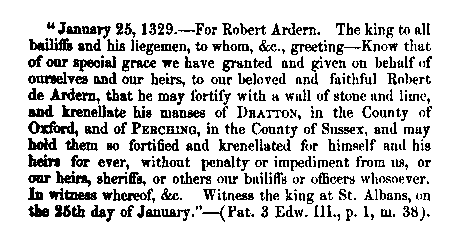

Perching was now in the hands of a powerful family of considerable note. They were important in the county, for thirteen legal decisions are extant on their tenure of properties in Sussex other than Edburton between 1190 and 1298. They also held estates elsewhere, from one of the chief of which, Addington in Surrey, much can be learned which is of interest for Edburton. They were important to the crown as holding Addington by a service of cookery at coronations. The obligation was no doubt a proud privilege, just as to this day are the duties of bearing certain of the insignia at coronations. The duty is defined as “a sergeantry of making a hotch-potch in a yellow dish in the king’s kitchen on the day of his coronation or by deputy”. Perching was not held by this service, but the succession at Addington and Perching had been the same. The first Norman tenant of both had been Tezelin, the Conqueror’s cook. It is not only that the two manors were so closely connected, nor even the flavour of the kitchen, that is the most significant, but that the family was so closely tied to the crown at a time when so many of the feudal lords were in revolt. Robert, the son of William, and his heir and successor at Perching, was a devoted royalist, in whom the king had such confidence as to allow him to fortify his manor-house. In 1264 a licence [to crenellate] was granted. Meanwhile, Robert had died, in 1261, and in 1268 the licence was renewed to his son, also named Robert. [Howe 1958, pages 8-9]

In contrast to Victorian times, the desire to crenellate a manor was not an aesthetic matter, nor an academic one. The king would have wished to ensure that his supporters were in a position to defend themselves. This was a period when the king and the barons were in dispute. Robert Aguillon was loyal to the king but his overlord, the Earl of Warenne was a militant baron. Relations between them were not good as this document of a prosecution for trespass from 1274 demonstrates:

To the sheriff of Sussex. Whereas the king, at the prosecution of Robert Aguillon, lately ordered him to move the men of John de Warenne, earl of Surrey, archers and other armed men, who wander about Robert’s manor of Percynges and about his other lands, and lie in wait by day and night for his men, and aggrieve and disquiet them, from the said manor and lands, and the archers and other armed men, although warned by the sheriff on the king’s behalf to depart quietly from the manor and lands, still remain there doing worse damage to Robert and his men, whereat the king is moved: the king therefore orders the sheriff, if the archers and men still remain there and refuse to depart, to take them and keep them in prison until otherwise ordered. [Calendar of the Close Rolls, Henry III, 27th March 1274, quoted by Howe 1958, page 9]

When the younger Robert died, in 1286, Perching manor alone had been providing him with an income of around £100,000 per annum in today’s money (calculated on the basis of the relative price of eggs). And he was the lord of many manors.

*The manorial status of Fulking is complex. It was once a component of the manor of Shipley, then became detached and was eventually absorbed by Perching [see Howe 1958, page 6 for the details]. The Old Farmhouse may have been the manor house.

References:

- Dave Bangs (2008) A Freedom to Roam Guide to the Brighton Downs. Portsmouth: Bishop Printers.

- F.A. Howe (1958) A Chronicle of Edburton and Fulking in the County of Sussex. Crawley: Hubners Ltd. [The definitive source on the early history of Perching. Most of the information presented above comes from Howe’s book.]

- L.F. Salzman, ed. (1940) A History of the County of Sussex, Volume 7: The rape of Lewes. London: Victoria County History, pages 202-204. [This contains a lot of detail on the early history of Perching, albeit in a much less readable manner than Howe. But, unlike Howe, it is just a click away.]

Updated 2nd March, 2013.

Currently popular local history posts:

South Downs Biosphere Reserve

Public relations events to promote the project are to be held at Devil’s Dyke Inn on March 17 (10am to 2pm) and at Adastra Hall, Hassocks on April 5 (11am – 4.30pm).

Photos of the South Downs

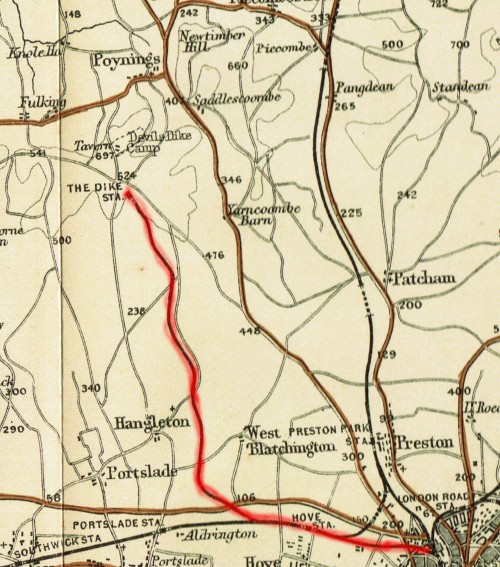

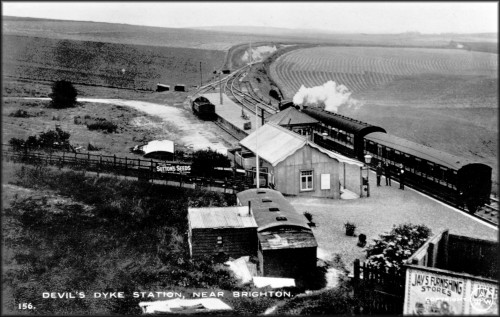

The Dyke Railway 1887-1938

Plans for a railway to link Brighton to the Dyke were first mooted in the early 1870s but did not receive parliamentary approval until 1877. It took another decade before the railway was finally opened. In addition to the usual legal and property issues that attend the creation of a railway line, the overall gradient of 1 in 40 posed a significant technical challenge as did the hard chalk rock found at the end of the route. Indeed, the terminus of the line fell short of the Dyke by several hundred yards because the gradient at that point made further extension impractical.

Over the first year of operation, some 160,000 passengers were carried. The only intermediate stop at that time was at West Brighton (now Hove) Station. The total distance was 5.5 miles of which 3.5 were on the slope of the Downs. The trip took twenty minutes (just as the 77 bus from Brighton Station does today). The first additional intermediate stop to be added to the line was Golf Club Halt in 1891. This was a private platform built on what was then the property of Brighton & Hove Golf Club and provided for the use of its members. Two further intermediate stops opened in 1905, both on the main Brighton-Portsmouth line: Dyke Junction Halt (later renamed Aldrington Halt) and Holland Road Halt. The fourth, and final, addition was Rowan Halt built in 1933 to serve the new Aldrington Manor Estate that was then being developed to the north of the Old Shoreham Road.

The railway remained in operation for half a century with the exception of a closure of three and a half years at the end of WWI. When the line first opened in September 1887, there were eight trains a day (five on Sundays) between Brighton and the Dyke (and conversely). In June 1912, there were eleven trains a day (one fewer on Sundays). In November 1938, the penultimate month of operation, there were sixteen trains a day (half as many on Sundays). Conventional locomotives were used for most of the line’s life although a prototype steam railbus (essentially a large bus mounted on two bogies) was employed on the line in the mid-1930s and proved to be very popular with customers.

Although useful to members of the various golf clubs situated between Brighton and the Dyke, the primary passenger function of the railway was to take day trippers up to the Dyke in the morning and bring them back in the evening. Demand was thus seasonal and weather-dependent. Many of these visitors would use the Dyke as the basis for a day’s walking. Teashops sprang up in the villages at the foot of the Dyke to cater for their needs. Fulking and Saddlescombe each had one and Poynings had four at one stage. For those unwilling to stray off the Dyke itself, refreshments were also to be had at the Dyke Hotel and at Dennett’s Corner which was only a few yards from the station. A secondary passenger function was to take residents of Edburton, Fulking, Poynings, Saddlescombe and the various local farms into Brighton. The roads were poor and buses did not reach the Dyke until the 1930s. If you were not wealthy enough to have the use of a horse or, later, a car, then access to Brighton was difficult before the railway was built. Locals used the service to shop in Brighton and others commuted to work there.

Passengers were the main focus of the railway. But it also offered a goods service and this was economically important to the local villages. A goods siding was built at the Dyke Station in 1892. Coal, coke, cattle fodder and parcels were transported to the Dyke and collected from the station by horse and cart or by the local coal merchant. The latter then delivered both coal and parcels in the villages (and was paid a penny for each parcel by the railway company). On the return journey, goods wagons would take straw, hay, grain and local produce from the farms and market gardens into Brighton. Goods traffic was discontinued in January 1933.

Golf Club Halt was a request stop rather than a real station. It never appeared in the rail timetables. However, the wishes of club members were reflected in the details of those timetables. There was a platform but that was all. You couldn’t buy a ticket for it — you had to purchase a ticket for the Dyke Station. If there were golfers on board, then the train would stop there to let them off. On the return journey, the train would stop to pick up golfers if they were visible on the platform (after dark, they struck matches). The platform was (and is) some fifty yards north of the clubhouse, perhaps because the gradient adjacent to the clubhouse made a more convenient location infeasible. However, from 1895 on, when a train was about to leave the Dyke Station, a bell would ring in the clubhouse alerting departing members to the need to make their way to the platform immediately. Although club members had mostly taken to using motor cars in the 1930s, the halt remained in use (especially when the weather was poor) until the railway itself was closed.

What remains of the railway today? South of the bypass, Brighton’s urban sprawl has eradicated almost every trace of it. Aldrington Halt remains in use, albeit unmanned. North of the bypass, the route is still visible either from the sky or on the ground, but you need to know what to look for. The cuttings and embankments that were needed to make the uphill route possible are there and dense scrub marks the location of the track for several long stretches. A public cycleway (the Dyke Railway Trail) running parallel to, or along, the track extends from the bypass to Brighton & Hove Golf Club. From then on, the line of the track runs through private farmland but a strip of scrub reveals its presence. Much of Golf Club Halt, which was never more than a platform, is still there, hidden in the scrub. At the northern terminus, Devil’s Dyke Farm now stands where Dyke Station once was. All that was left of the station a dozen years ago was a small chunk of the platform.

Further reading:

- Paul Clark (1976) The Railways of Devil’s Dyke, Sheffield: Turntable Publications. [This booklet contains a detailed history of all aspects of the line and includes maps, photos, transcripts of relevant documents, and engineering diagrams.]

- Peter A. Harding (2000) The Dyke Branch Line, Byfleet: Binfield Print & Design. [Reprinted in 2011, this well illustrated booklet is currently the most readily available work on the history of the railway.]

- Hove Borough Council (1989) Dyke Railway Trail [PDF], a four page leaflet. [The map contains a number of errors: e.g., both the exact railway route and Golf Club Halt are mislocated. Nevertheless, the leaflet is still useful if you plan a walk in the area.]

- Barry Hughes (2000) Brighton & Hove Golf Club: A History to the Year 2000. Brighton: B&HGC. [Pages 27, 30, 33, 42, 48, 60-61, and 115 contain material relevant to the railway and Golf Club Halt.]

Some other material relevant to the C19 and C20 history of the Dyke:

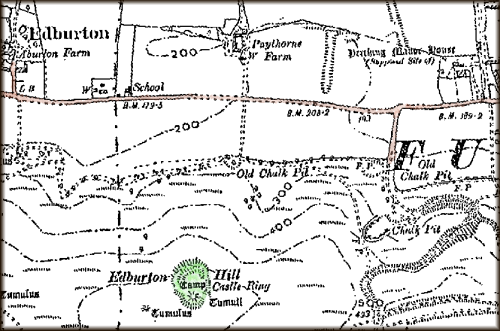

Castle Ring

Castle Ring[s], also known as Edburton Castle or Edburton Camp, sits at the peak of Edburton Hill on the Downs halfway between Fulking and Edburton. It cannot be seen from the road. It can just be seen from the South Downs Way as you descend the western slope of Perching Hill, but only if you already know what you are looking for. There is no marked footpath to it. Getting there entails a steep climb across a field. But it is worth the effort. The structure itself, which has ‘scheduled monument’ status, is impressive and the views over the Weald are the equal of those from the Dyke.

Castle Ring has not been excavated and rather little is known about it or what it was for. Even the date of construction is uncertain although most sources point to the end of the 11th century, immediately after the Norman conquest. Volume 1 of the Victoria County History, published in 1905, refers to it as “this curious little work” and remarks that:

There no traces of masonry, and, as far as one can see, there is no supply of water near. Why it should be placed here is a mystery, unless, indeed it was a signalling station visible perhaps from Pulborough and Knepp Castle.

[Page 1905, page 476]

Volume 7, published in 1940, is likewise terse:

It has a very small rectangular bailey [= external wall], and an equally insignificant motte [= mound]. It is probably an outpost castle constructed soon after the landing in 1066. The boundary of the rape [= administrative district], and the division between East and West Sussex, passes immediately to the west of the motte ditch.

[Salzmann 1940, page 202]

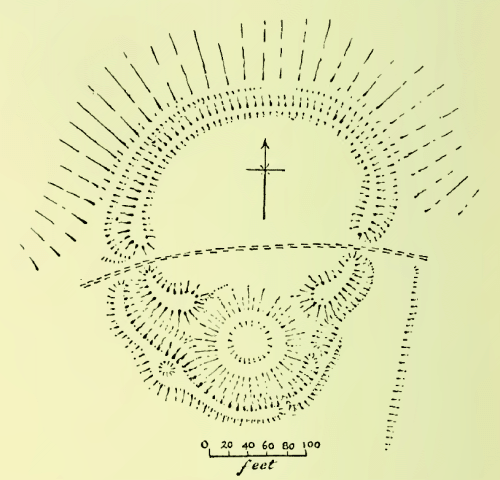

Hadrian Allcroft’s magisterial Earthwork of England, published in 1908, still provides the most comprehensive archaeological description and discussion of the site:

Edburton Camp crowns a prominent hill-bastion of the northern face of the Downs .. In position it resembles Chanctonbury, as also in having one vallum [= earth rampart] and one fosse [= trench or moat], but it is singularly small even for a Sussex fortress, measuring no more than 60 yards across the widest diameter of the diminutive area, and in plan is quite unlike any other hill-top fortress. The line of the defences follows the oval contour of the exiguous hill-top on all except the southern side, where it is interrupted by a depressed mound of 100 feet in diameter, the fosse looping outwards to cover the base of the mound. The whole plan, therefore, is at first sight much that of the simplest form of mount-and-bailey fortress. But on close examination this resemblance will be found to be less real than apparent: the mound is too low to have been a motte, for it does not attain even to the 10 feet or so of vertical height reached by the vallum on either side of it, and it can never have been much higher than it now is, for had it been greatly wasted the fosse along its southern side must have been far less deep than now, and the depression at its centre must have disappeared. More important still, the fosse is not carried round the northern side of the mound, and apparently never was. The vallum to east and west rises to more than average height, but ends abruptly, neither reaching to the mound nor being continued round its base. A shepherd’s path traverses the area, passing the vallum by openings seemingly both original in the eastern and western sides. From the western entrance commences a second vallum, which follows the edge of the fosse right round the southern angle of the camp and then gradually disappears. It is at its highest in the angle where the fosse bends to accommodate the mound, and at this point is a circular depression about 8 feet wide in its broad summit. The great mound is neither flat-topped nor ringed by a vallum, but in its centre has a cup-shaped basin 33 feet in diameter and perhaps 3 feet deep. The ground to the south of the camp is to all intents level, but there are no signs of any outworks, unless a small and low mound 80 yards to the south-west be such. From the eastern entrance, where the slope is steeper, a very slight scarp is traceable for some 40 yards in a direction west of south. It is perhaps an old plough-mark. Fragments of pottery are to be found in the mole-casts along it. Further to the west lie several barrows which have yielded very early remains.

Of all the South Down camps this is the most puzzling: it would indeed be difficult to find another like it anywhere. It has been said of it that it “has nothing in common with the hill-forts (of Sussex).” One would rather say that it has everything in common with them except the mound. The nearest analogy to the mysterious mound with its depression is that within the area of Mt. Caburn, which would seem to have been a reservoir. It is much to be regretted that Pitt-Rivers, who explored the one, did not examine the other also; and small as Edburton Camp is, the task of exploring it completely would be an easy one. Meanwhile there is nothing but conjecture. Some have suggested that the mound was a beacon. If that were so, what was the need of the rest of the earthworks? Yet they are all apparently of one plan with the mound and of one date. Others believe it to be a Norman fortress; but against this is the absence of any encircling fosse about the whole of the mound, quite apart from the exceptional character of the site, at an elevation such that no water can have been found within several hundreds of feet at any time during many centuries past. Edburton must remain a mystery until the spade is brought to unlock its secret.

[Allcroft 1908, pages 659-662, footnotes omitted]

Recent reference material (i) lists the structure as “Early Medieval/Dark Age — 410 AD to 1065 AD” but then immediately goes on to say that it is believed to be Norman; (ii) claims that the central depression resulted from “mistaken barrow digging in the 19th century” but offers no evidence for this speculation; and (iii) suggests that the use of Castle Ring was “more likely to have been administrative and residential” than military but fails to address the implications of the apparent absence of any water supply. It seems that Allcroft’s conclusion — “Edburton must remain a mystery until the spade is brought to unlock its secret” — is as true today as it was more than a century ago.

References and further reading:

- A. Hadrian Allcroft (1908) Earthwork of England. London: Macmillan, pages 659-662.

- William Page, ed. (1905) The Victoria History of the Counties of England, Sussex, Volume 1. London: Archibald Constable, page 476.

- L.F. Salzman, ed. (1940) A History of the County of Sussex, Volume 7: The rape of Lewes. London: Victoria County History, page 202.

- Edburton Castle Ring — Books and Resources.

Currently popular local history posts:

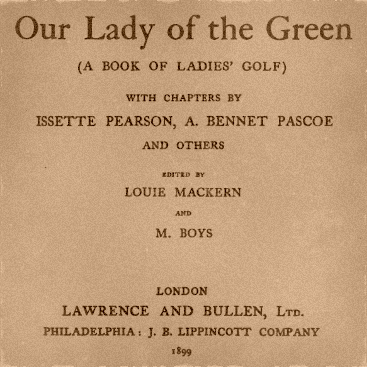

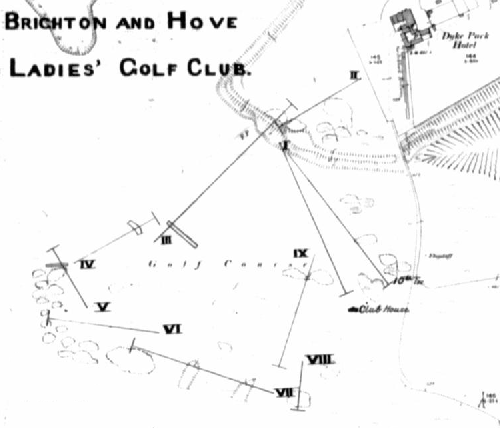

The Ladies’ Golf Course

As you drive up the Devil’s Dyke Road, north of the bypass, you reach a point where you are less than half a mile from four different golf courses. That’s a lot. By contrast, the whole thirty mile stretch of Downs between Shoreham and Hampshire contains exactly as many, “two at Goodwood and two north of Worthing” (Bangs, page 159). For nearly fifty years, if you had followed the road a bit further, to the very top of the Downs, you would have come to yet another golf course. This one was immediately adjacent to, and to the south-west of, the Dyke Park Hotel. The associated club was an offshoot of the Brighton & Hove Golf Club [B&HGC] and membership was exclusively female: the Brighton & Hove Ladies’ Golf Club.

The course existed from 1891 to 1939. It was served by the Dyke Station, located to the south-east just off the map image shown above, over almost the entire period. It was thus very conveniently situated for members who lived in Brighton or Hove although it seems that most arrived “by pony and trap or by bicycle, or later on, by motor car” (Hughes, page 64). It had its own clubhouse and catering would also have been readily available at the Dyke Park Hotel.

As a consequence of WWI, the course closed for the period 1916-20 but members used the grounds and the clubhouse to entertain wounded soldiers. Play resumed in 1920 and the club began to attract younger players. The outbreak of WWII saw the final end of both club and course. The railway closed in December 1938 and the Ministry of Defence requisitioned much of the Downs. The clubhouse was completely demolished, possibly by Canadian tank crews. After the war, former members of the club had to fall back on their status as associate members of B&HGC if they wanted to play.

Well, probably not. But Miss A.M Starkie-Bence used to play on the course and she was a distinguished Sussex golfer active in the final decade of the nineteeth century, one who held numerous course records and medals. [The image derives from an 1892 issue of The Gentlewoman.]

Further reading:

- Dave Bangs (2008) A Freedom to Roam Guide to the Brighton Downs. Portsmouth: Bishop Printers.

[Pages 158-162 contain a rather comprehensive discussion of the many golf courses that have existed on the fringes of Brighton over the years.] - Barry Hughes (2000) Brighton & Hove Golf Club: A History to the Year 2000. Brighton: B&HGC.

[Chapter 4, pages 62-67, contains the definitive history of the Ladies’ Golf Club.]

With thanks to B&HGC for their assistance and for granting permission for the use of the map.

Amended 30th January, 2013.

Some other material relevant to the C19 and C20 history of the Dyke:

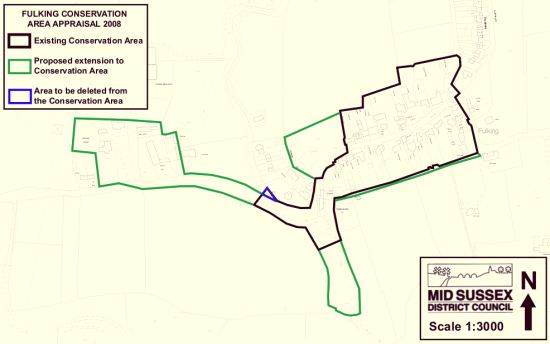

Fulking Conservation Area

In November 2007, Mid Sussex District Council (MSDC) held a public meeting and an exhibition to illustrate the work that had been carried out on Fulking Conservation Area Appraisal over the proceeding months. The public meeting was held in the Village Hall, the Street, Fulking on Thursday 12th November 2007. The exhibition was held in Hurstpierpoint Library, Trinity Road, Hurstpierpoint from Monday 26th November until Friday 7th December. At the time, exhibition panels were also made available on the MSDC website.

The exhibition included a detailed assessment of the character of the conservation area, suggested a number of changes to the boundary and provided some potential ideas for enhancement. Questionnaires relating to the draft management proposals were made available at all of the locations listed above. The deadline for the receipt of comments was Friday 14th December 2007.

The exhibition included a detailed assessment of the character of the conservation area, suggested a number of changes to the boundary and provided some potential ideas for enhancement. Questionnaires relating to the draft management proposals were made available at all of the locations listed above. The deadline for the receipt of comments was Friday 14th December 2007.

In May 2008, as a result of local consultations, the MSDC Planning Policy Division issued the Fulking Conservation Area Appraisal Document (PDF).

Another document (PDF) summarised the comments the Council received to the questionnaire and set out responses prepared by officers on behalf of the Council to the main issues raised. Wherever possible suggestions made by the public were included in the appraisal document.

It should be noted that, although MSDC agreed in principle to the extended conservation area, it has not been been legally adopted. Thus the original conservation area still stands.

Updated and corrected, 5th & 9th December 2013.