Off the Beaten Track in Sussex appears to have been the only book that Arthur Stanley Cooke ever wrote. There were two editions, one published in 1911 by A.S. Combridges of Hove and another in 1923 by Herbert Jenkins of London. The latter, at least, must have sold well because numerous copies can be found in stock at used book dealers to this day. A contemporary reviewer commented that “No detailed criticism is called for. The author knows and loves the county well, and knows how to put his impressions into words. .. [He] has clearly had a good opportunity of writing an interesting book, and he has not neglected it.” [The Spectator December 30, 1911, page 25]. A feature of the book is the large number (160) of illustrations, mostly pen and ink, by a variety of Sussex artists including the author himself. Cooke writes as a well-educated Edwardian gentleman whose interests are archaeology, architecture, onomastics, history and landscape. In the extract that follows, the author leaves Poynings, gives Fulking a somewhat cursory inspection, and ends with a meditation upon the merits of Edburton. Apart from this passage, there is much else in the book to interest the local resident including material on Beeding, Bramber, Botolphs, Buncton, Chanctonbury, Coombes, Lancing, Shoreham, Sompting, and Steyning, inter alia. [Thanks to Gill Milner for drawing this book to the local history editor’s attention.]

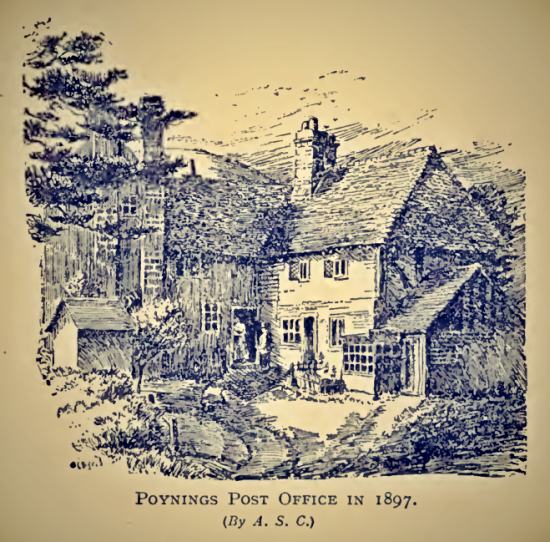

Poynings has few interesting old houses. The old Post Office is perhaps the best of them, and its interest is rather of the eighteenth century than of an earlier date; of the day when houses were built and appointed in a homely rather than an artistic or appropriate fashion. I use the word in its humble sense. Rooms were low pitched, small and not too pretty. Ornamental details were rigorously excluded, and most things done something after the style of a doll’s house, rather than for the daily use of “grown-ups.” Witness the tiny shop window and even this is altered since the sketch was made.

You leave Poynings by the western road, and at the entrance of Fulking there is a half-timbered house, which makes a good sketch, with the downs for background. Clappers Lane, known to but few, winds a green way north of this house for several miles, and where the stream crosses the path there is a spot which would be difficult to get a sketcher by without a rope or some equally persuasive argument!

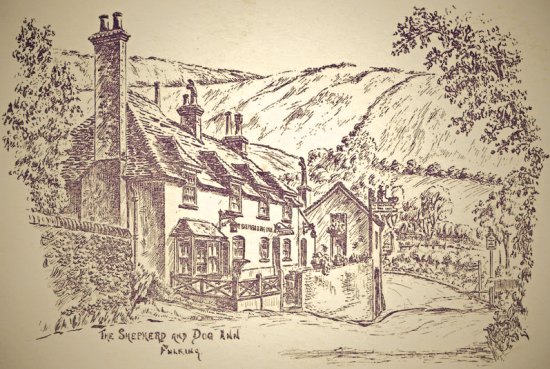

The Shepherd and Dog Inn stands at the western end of the hamlet, by one of the sharpest turns that Sussex roads, noted for sudden crinks, can show. It is a picturesque spot, for at the bend the stream which comes from under the hill not a hundred yards away, gushes into the ditch, close by a quaint little pump-house erected to the memory of John Ruskin. Here is the sheep wash, and when that is in progress, there is subject enough for any artist.

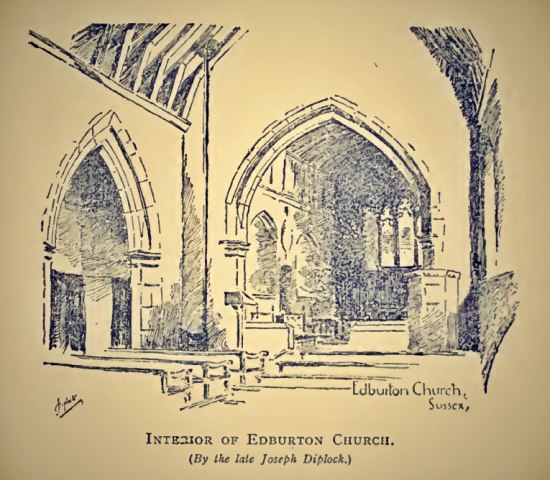

Edburton, the parish church for Fulking, lies still farther on. It will probably be somewhat of a surprise to those who happen to know how near it is to Poynings, and have not thought it worth a visit. The latter church lies so directly under the eyes below the Dyke, that the more retiring and older building is seldom seen. Edburton Church stands embosomed in trees about a mile west of Fulking, and although it cannot be said to vie with Poynings in originality and beauty, still it is by no means to be despised therefor.

It is large and full of interest for the antiquarian. The restoration, with scarcely an exception, has been lovingly carried out. The simple seating has distinct merit, both as to design and mouldings, and anything which had age to recommend it has been retained, and wisely, too. It is a well-known fact that everything made prior to the beginning of the reign of shoddy and veneer was, in the main, well proportioned and artistic in design and ornament. That is why it is nearly always safe to copy old models.

Edburton possesses one of the only three cast-lead fonts in our county, and perhaps the oldest of them. It is late Norman, and has panels of floriated design at the base, with a similar encircling pattern above, surmounted by an arcade of tref oiled arches. There are only twenty-nine of these fonts in all England, and therefore they are of great interest. Simple in form of course they are, and usually stand on a stone or wooden base. The lead is about an inch thick, and shows signs of the pattern being a repetition of the same segment of wooden mould impressed in the sand or clay that received the molten metal. The one at Pyecombe is somewhat similar, but more ornate; and that at Parham is a unique specimen of the Decorated period, being ornamented with shields and bands of inscriptions in beautiful Lombardic capitals.

One of the bells is amongst the oldest in Sussex, and bears two shields and an octagonal medallion. One of the shields has the crossed keys and a dolphin, a laver, a wheatsheaf, and a bell in the fourquarters.

The history of Edburton, Adburton, or Abberton as it is differently styled in old records is of the quiet kind, suited to its situation. Once only does the tide of spiritual war seem to have reached it, when Michael Jermyn, the Rector, would not “conform” in 1655, and was ejected after thirty years’ ministry, Nicholas Shepheard being installed in his place by the Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell.

Edburton is connected with the Metropolitan of England, the advowson belonging to Canterbury. There are traces of no less than three altars, one of which was founded in the north transept by William de Northo in 1319, in honour of St. Katherine.

This modest list exhausts the historical interest, and apart from an antiquarian excitement which fluttered for a brief space over some Roman remains, chiefly notable for their scantiness, Edburton may be compared with the violet in its retiring nature. Like that simple floweret, it must be sought to be found, if one may descend to a truism so evident, yet justifiable. The charms of scenery are not always realised at a glance. Where these are so instantly in evidence, there is usually little more to discover; and where only an occasional visit is made, it is enough for the time being the eye is satisfied and asks for no more just then. But if it is often dwelt upon, one gets to wonder whether it is quite so fair as it seemed at first and then the less striking locality has its day of quiet examination, and begins to improve on acquaintance. Sunrise, sunset, and the different moods of weather help to make a beautiful panorama worth seeing; but it is only one view, and tires the eye after awhile; whereas the quieter beauties of winding road or stream, of hedgerow or copse-corner, will bring the artist up with “a round turn” where least expected.

So it is with the scenery in and about Edburton. There is nothing of the startling order to attract one, but there are lots of subjects to linger over; bits of colour, groups of trees, and fine hills both near and far. A little north-east of where my first view is taken, the village makes a foreground group of roofs not to be despised in colour or in line, and beyond it the grey old church with ruddy tiles fills the right of the picture to entire satisfaction; while the cornfield fronting all ripples in wavelets of yellowing green in August, to a delightful belt of trees at the foot of the nearest hill; and far-away Chanctonbury hangs like a grey cloud to the summit of its Down.

This is the view you will see as you cross the upland field to the steep ascent. By the time you reach the top you will have had enough of climbing and be glad to rest on the grass and take in fresh breath and the wider wealden view, before catching the train at the Dyke Station.

Arthur Stanley Cooke (1923) Off the Beaten Track in Sussex, London: Herbert Jenkins, pages 57-61.

[The text is reproduced exactly as it originally appeared with the exception of the spelling of certain place names. In deference to Google, all the place names appear with their current spellings.]

Currently popular local history posts: