It seems that the SDNPA is especially keen for farmers to react to their new Draft Partnership Management Plan.

Category: Farming

One man went to mow

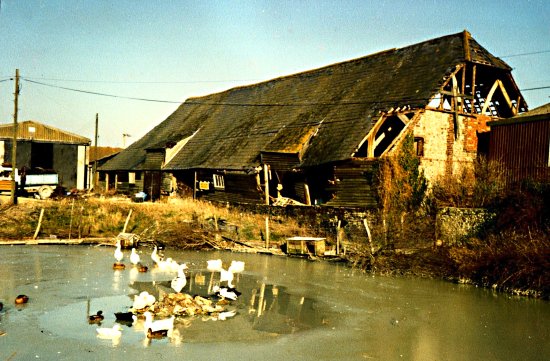

Perching Barn

Until relatively recently, Perching Manor was a farmhouse and the area to its immediate east was the farmyard. There had been a farmyard in that location for hundreds of years. Farm buildings come and go, of course, but the largest building dates back to the eighteenth century. Houses have human residents who leave a history. We know quite a bit about the history of Perching Manor itself and even of the fortified building that preceded it and of the manor more generally. But farm buildings give rise to few records. The owls, rodents and feral cats who take up residence pass through anonymously, untroubled by police, lawyers, census takers and registrars of birth, death and marriage. Thus most of what is known about the history of this now former farmyard is of recent vintage — the last eighty years or so.

The largest, and most distinguished, component of the farmyard is Perching Barn. This is a Grade II listed eighteenth century building with weather-boarding on a flint base. The roof is slate, hipped at the north and half-hipped at the south. A large building today, the map shown above suggests that it was quite a bit larger still in the mid-nineteenth century.

Perching Barn was a fine example of a Sussex threshing barn. It had a wide entrance in the centre of the (long) side that faced west and was high enough to allow a threshing machine to be positioned and operated in the centre of the building. Sheaves of corn were loaded from both sides of the machine and the grain was then stored on either side of the building. Once threshed, the straw was ejected from the back of the thresher to the outside of the building. When not in use during harvest it was available for other uses — such as village barn dances and parties.

To the immediate north of the barn stood a stable for the farm horses. In later years, as tractors replaced horses, it was used as a storage shed and workshop. To the north east, there was a two-storey building, with cattle pens at ground level and a grain and cattle feed store above. Feed was delivered to the cattle as required, via a chute. Calf pens and a storage shed were situated at the south end of the building.

Some time during the 1930s or 1940s, a man known only as Martin lived in the lower half of a two-storey barn situated behind this building, on ground that fell away sharply towards the stream to the north east. It seems that he was ex-army and well educated, but chose to live there on an earthen floor, using old sacks as bedding. From time to time he became very ill and was moved to the workhouse at Chailey, but as soon as he recovered he would walk back to his simple home in Fulking. It is thought that his income was mainly from an army pension, but he supplemented this by chopping wood and doing odd jobs at Perching Manor for which Henry Harris is thought to have paid him 10 shillings a week.

George Greenfield was the local tramp. He may have been the George Greenfield who was born in Steyning around 1884. He lived rent-free in the ‘duck hut’, an open fronted, lean-to shed located at the southern edge of the farmyard. The shed had an open front and faced Perching Drove and the pond. George walked with a stick and had a dog. He was well known around the village and on most evenings could be found sitting in the same place at the Shepherd and Dog. He was known as the ‘threshing machine feeder man’ as this was his job when the contractor arrived in the district for the autumn/winter threshing period. In summer he did no work at all. Like Martin, his bedding was sacking and he hung sacks across the front of his hut to keep out the wind and rain. He cooked on a brazier and in winter he moved this inside the hut to provide heat. However, this meant that the hut filled with smoke, as there was only a small gap just below the roof for it to escape through. When he became ill, George was also taken to the workhouse at Chailey, but once recovered, he too always walked back to his shed, where he eventually died.

As farming became more mechanised, the barn was divided up. Half was used as a grain store, whilst the other half became a milking parlour and dairy. Later, Brian Harris, who was the farmer at the time, switched to arable production only. This decision was brought about partly because it was becoming impossible to find a cowman prepared to work the unsocial hours associated with livestock production and partly because of changes entailed by European Union farming policies. As a consequence, the barn became largely redundant.

In 1984 the Crown sold Perching Manor Farm to the National Freight Corporation. The latter sold it to Brian Harris in 1986. In the same year, Terry Willis, a developer trading as Sussex District Estates, came to Fulking and started buying redundant farm buildings for conversion to private dwellings. This was not straightforward as most had agricultural restrictions attached to them, but once these were lifted and planning permission had been obtained, the development programme began. In 1987, Brian Harris sold his redundant and derelict farm buildings to Willis. The sale included the barn, the stable and the grain store/cattle shed. Terry Willis, with the aid of an imaginative architect and some competent builders, converted these dilapidated buildings into attractive private residences during the 1990s (see the appendix below).

Tony Brooks

[Copyright © 2013, Anthony R. Brooks. Adapted from Anthony R. Brooks (2008) The Changing Times of Fulking & Edburton. Chichester: RPM Print & Design, pages 182-185.]

Appendix

The 1990s Willis development process in pictures:

Currently popular local history posts:

Fulking 1922-1956

[The essay that follows was written in 1957 by Edgar Bishop, a central figure in village life during the period that it covers. He lived in Brook House and ran a large market garden from land mostly on the west side of Clappers Lane. Some thirty to forty people worked there and, with Henry Harris, he was one of the two major local employers.]

In looking back over the past thirty four years it is quite astonishing to note the many changes which have taken place in the village life: in 1922 when we came to the district, Fulking and Edburton were very quiet isolated Downland villages, the Dyke Railway being practically the only dependable link with Brighton, barring, of course, one’s legs. I well remember arriving at the Dyke Station in that thick mist, wondering how on earth I was going to find Fulking — but with the friendly help and guidance of a native I was piloted down the hill and arrived safely in the village.

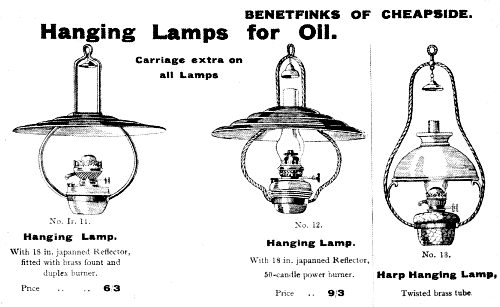

How things have changed since those days of long ago — paraffin and colza [rapeseed] oil was the only means of light so that the most important morning task of every housewife was the cleaning, trimming and refilling of the lamps. Telephones did not exist and when the G.P.O. started encouraging people to use them it was largely a question of getting a sufficient number of subscribers together to warrant the main lines being laid — in the end thirteen of us grouped together and agreed to have the phone installed, this being the minimum number acceptable to the G.P.O. Then came the difficulty of getting the Brighton Corporation to lay cables for electricity and here it was only with considerable and joint pressure from both the Poynings and Fulking inhabitants that the Corporation agreed to extend the mains through from the London Road side.

The one and only school — the Church School (now Boundary House) provided the education but unfortunately disagreement arose between the East and West Sussex Authorities over the administration, and the church lost the School. Incidentally the School had been given under a deed of trust by Lord Leconfield but unfortunately it lapsed and so bureaucracy stepped in and the school was closed.

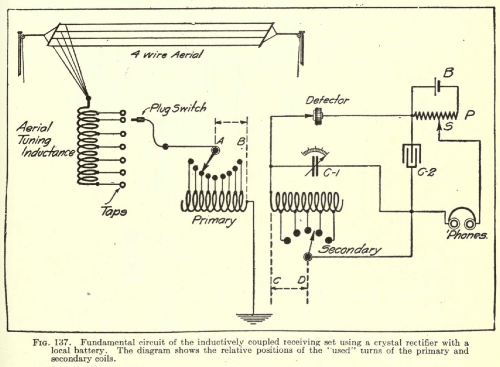

Wireless was in its infancy — we all remember the elusive crystal — entirely dependent on batteries which required constant renewal — and television was of course unknown. Very few motor cars passed through the villages and there was no motorised farm machinery, with the exception of steam engines — the mechanised plough consisted of two steam engines posted on opposite sides of a field with the plough being drawn across by means of a cable.

The present Mission Church of the Good Shepherd in Fulking was then the men’s ‘Club Room’ and library and the Village Hall did not exist. It should be remembered that it was only due to the unceasing efforts of the then Rector, the Reverend Evans, who was responsible for obtaining a grant from the Chichester Diocesan Finance Board, that sufficient money was made available to build the Church Hall, after which the ‘club room’ was altered and devoted entirely to church services.

When the Southdown Bus service started — I cannot remember in which year that was — what a revolution ensued: villagers hitherto confined to their homes now trooped into Brighton, especially on Saturdays, for the first time. It was not long after the advent of cars and buses that the Dyke Railway ceased to function.

More recently, I believe it was in 1952, main water was brought to the village, thereby doing away with the water supply from the spring and pumped up to the storage tanks by the Ram: this has been instrumental in bring water to almost all the houses and cottages and is obviously the forerunner of main drainage. It is gratifying to know that the Crown who now own the Ram House, has undertaken to maintain it in a good state of repair.

Looking back over these years one cannot help somewhat regretting the passing of so much that was valuable in the life of our villages, and wonder whether all the modern means of comfort and transport have brought a real increase of happiness to the country folk.

Looking at Fulking particularly, especially on a Sunday, it seems to have become a thoroughfare for hundreds of motorists, motorcycles and coaches, which tear through our old time village, very often at most dangerous speeds. We are all caught up in a social revolution but whether it is leading to the greatest happiness of the greatest number, only time will tell.

Edgar H. Bishop

[This essay first appeared in issue 35 of St. Andrew’s Quarterly, July 1957. For more information about the author, see Anthony R. Brooks (2008) The Changing Times of Fulking & Edburton. Chichester: RPM Print & Design, pages 64, 81, 83, 165, 180, 345 and 347.]

Currently popular local history posts:

Water Polluted by Nitrates

May 3rd: There’s a rather more informative report up at The Argus today.

Downs Solar Farm Proposed

The View from Pippins, Spring 2013

In this unseasonably cold weather the trees and bushes on the Downs seem to be “oozing” rather than bursting into life! There are changes every day and there is a gorsebush bravely blooming halfway up to the top. Mind you, the old saying that when the gorse is out of bloom then kissing is out of fashion suggests that it’s generally blooming somewhere!!

Our garden aconites have come and gone and the primroses rehomed from my mother’s Kentish garden are brightening up the bank, mirroring those further up the bridlepath opposite “Downside”.

Wood anemones are flowering and wild garlic leaves are coming up…the latter delicious made into a pesto with walnuts (try kent cobnut oil or walnut oil) or used to wrap butter around a chicken breast: Yum!!

We have lambs at last! Two sets of twins, little black rams to Molly and a white girl and boy to Darcy with three more ewes to lamb, although two of those are not looking very pregnant!

We are keeping the flock up by the house in this cold weather but they will be back to the Shepherd and Dog once they can cope without a shelter, and are big enough to escape the fox.

Schmallenberg

The threat of Schmallenberg virus is sadly still very much hanging over UK farmers this Spring, to compound the trials of those who are also losing lambs to the snowy weather. A report on the radio this morning asked us all to support them by buying English lamb as often as possible and I’m sure we don’t need too much encouragement.

A little background to this new disease .. It is named after the town in Germany where it was first identified (coincidentally twinned with Burgess Hill!) and is an “orthobunyavirus”, spread by midges similar to the Akabane virus found in the hotter parts of the world. Its epidemiology can therefore be cautiously predicted using that virus as a model, and it does seem that affected animals, primarily sheep and cattle, become immune in subsequent years and will give birth to normal offspring the following season. Sadly the lambs and calves born to vulnerable (i.e. non-immune) adults infected at the crucial stage of pregnancy (25-50 days for sheep, 70-120 days for cows) are born with abnormalities such as fixed and inflexible joints, a twisted neck or spine, domed skull or a short jaw, deformities usually incompatible with life, and very often needing a caesarean to deliver them. As you can imagine this plays havoc with the farmers profit margin.

We are keeping our fingers crossed that our little flock of Wensleydales will not be affected. It is hard to assess the local risk as a proportion of lambs are always still born for various reasons, and local farmers have only just started lambing. Let’s hope this freezing weather will have at least seen off the affected midge population – every cloud…..!

Pippins

Farmers in Fulking: A History of the Harris Family

My grandfather, Henry Harris, came from a farming family that had farmed in Dorset for about two hundred years. In 1891 he moved to Silton Manor, a farm of about 400 acres near Gillingham in Dorset. His son, my father, was also called Henry. Dad was one of a family of seven boys and six girls. The boys all became farmers and the girls, with one exception, married farmers. Five of Henry’s brothers fought in the 1914-18 war. They were all in the Dorset Yeomanry, as most farmers’ sons were and all returned without serious injury. My father was in Egypt and Palestine fighting the Turks and apart from being stung by a scorpion and a few bouts of dysentery was unscathed. In 1991 a centenary gathering was held at Silton Manor and about sixty relatives and other folk connected with the Harris family attended. Some came from as far afield as New Zealand and one from Zimbabwe. Two coaches were hired to take the guests on a tour of the Dorset farms where members of the family had once been tenants.

Over time the family had been able to purchase the farm and the size of the holding had been greatly increased. Six of the seven sons gradually left Silton once they had saved enough money to branch out on their own, leaving the youngest brother as tenant at Silton, until, at a later date, he was able to buy out his brothers. My father (Henry) married my mother Amy in 1920 and left the family farm in Dorset in the same year. At first Amy stayed behind while Henry moved to Sussex and rented a large farm of about 800 acres in Fulking called Perching Manor. This was in Crown ownership and later more land, adjoining the farm, belonging to Brighton Corporation, was rented. The land associated with these farms had become very run down and it took several years to return the land to good health. Amy came out to join her husband in 1922.

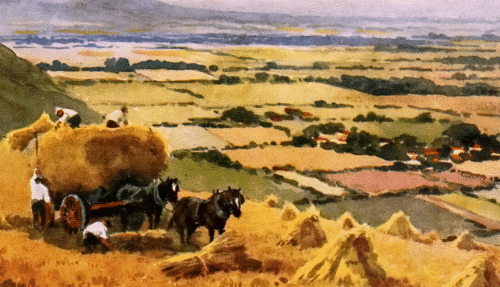

At that time there were no tractors and all the cultivation was done using heavy horses of which there were about ten at Perching. The carters started start work at five o’clock in the morning and stopped at half past three in the afternoon. It took two horses and one carter with a single furrow plough, to plough one acre a day. At the end of the day they then brought the horses back to the stables, fed them and bedded them down for the night.

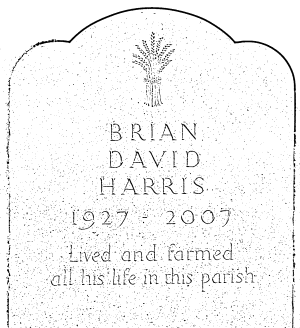

It was not long before Henry and Amy’s family had grown considerably. Their eldest child Henry, was born in 1926, Brian came along in 1927 and Geoffrey in 1929. They were followed by Susan in 1932, Edwin in 1936 and Alban in 1940. All the boys except Henry worked at Perching Manor Farm and Susan married a farmer.

The Harris household in 1943. Front: Amy, Alban, Edwin, Susan, Henry. Behind: Brian, Adolfo Marine [POW], Henry, Carlo Mazon [POW], Geoffrey.

Henry won various scholarships first to Oxford and then to American Institutions. He later became a professor aged 23. He took out American citizenship and spent the rest of his working life teaching classics in the USA and Canada. He retired to Vancouver Island in British Columbia and died in March 2007.

A large part of the farm was on top of the Downs where there were cottages for the farm labourers and stabling for the horses. A large flock of sheep was maintained and the land was kept fertile by folding them over land that was used for growing turnips, swedes and various brassica crops.

Kenneth Rowntree, 1946

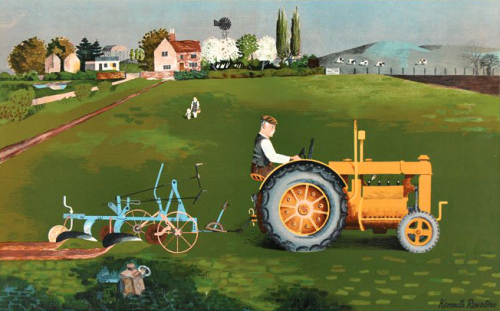

Henry Harris was a good farmer and soon gained respect among the farming fraternity. In the early years, it was a mixed farm with a large dairy herd, a flock of sheep and a large arable acreage. In 1937/8 Henry bought their first tractor: a Fordson. From then on cultivation became easier. The tractor could pull a two-furrow plough and this meant that three acres a day could be ploughed.

When war was declared in 1939, farmers were pressed into increasing productivity. Perching became much more mechanised and the acreage put to the plough was increased. A greater variety of crops was grown, including flax, potatoes and other vegetables. Any land worked by hobby farmers that was considered unproductive was confiscated and handed to more efficient farmers for the duration of war. My father’s acreage was considerably increased by the scheme.

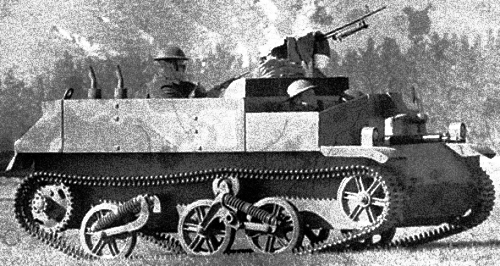

In 1941 all of our land on top of the South Downs was requisitioned by the War Department for training the army in the use of live ammunition. This left us with only the north escarpment of the Downs for grazing and a fence was erected along the top of the Downs to keep our cattle off the artillery ranges. However, there was plenty of grazing on the ranges and the temptation was to leave the gate open and let the cattle get to the better pasture. It was during this time, whilst out on my horse looking for our quite large herd of cattle, that I came across a Bren Gun Carrier with some men from the electricity board mending wires that had been brought down by artillery fire. I enquired if they had seen our cattle and they directed me to an area where eight steers and heifers lay dead. Apparently a mortar bomb had landed right in the middle of them and this was the result. It was debatable who had left the gate open, but we claimed the Army was at fault and we were compensated £18 a head for each animal.

In 1942 three Italian POWs came and worked on the farm. They were billeted in the cellar at Perching Manor, which was a great help, as most of our young labourers had been called up. The Italians weren’t repatriated until 1947 and in the meantime we also acquired two German POWs who returned home in 1948. Before the Germans left we were allocated two Latvian displaced persons. One left for Canada after about 3 years, the other, Rudolf, remained at Perching for his entire working life.

In 1947 we purchased our first combine harvester. A Minneapolis Moline, which made an 8ft (2.4m) cut and was not selfpropelled. Looking back, it was a rather a ‘Heath Robinson’ affair. But at that time it transformed harvesting. The farm had by now become highly mechanised with several caterpillar tractors and other modern equipment and in 1948 two more combine harvesters were purchased.

The Harris family in the late 1950s. Seated at front: Amy, Henry, Susan. Seated behind: Alban, Brian. Standing at rear: Edwin, Henry, Geoffrey.

In 1950 my father formed a partnership between himself and four of his sons (Brian, Geoffrey, Edwin and Alban). The farm was considerably enlarged in the 1950s with the largest addition being a 250 acre farm purchased at Findon, along with another of 160 acres at Small Dole. By 1960 the Harris holding was in excess of 2000 acres, about half of which was owned by the family and the other half rented.

By this time our milking herd was long gone. It had to be disposed of because it had become too difficult to get staff willing to start very early in the morning and work a seven day week. Perching became an arable, sheep and beef farm, growing about 1000 acres of grain, mainly barley, and maintaining a flock of 1000 breeding sheep and a herd of 250 beef suckler cows. Most of the animals were fattened and then sold on.

Henry Harris died in 1961 aged 72 and his wife Amy in 1990 aged 96. Amy had lived at Perching Manor for sixty years.

Geoffrey left the partnership in 1964 and bought the Findon Farm from the business. He and his wife Josephine started Springs Smoked Salmon in the same year and in 1972 they sold the farm and concentrated on the salmon smoking business, which is still carried on by their two youngest sons.

Brian took over running Perching Manor Farm, as his brothers gradually branched out to run their own farms. Edwin went into sheep farming and is now retired. Alban (Shiner) has land at Pyecombe and Fulking and rears beef cattle.

Geoffrey Harris, 2007

[Copyright © 2013, Geoffrey Harris. This memoir first appeared in Anthony R. Brooks (2008) The Changing Times of Fulking & Edburton. Chichester: RPM Print & Design, pages 350-354.]

Editorial postscript: ill health forced Brian Harris to retire from farming in 2006. He died in July the following year and is buried in the churchyard at St. Andrew’s. His daughters took over running Perching Manor Farm.

Currently popular local history posts:

Perching Manor

Apart from St. Andrew’s Church, Perching Manor [Farmhouse] is the only Grade II* listed building in Fulking and Edburton. It is the eighteenth century farmhouse for Perching [Manor] Farm, and it retained its traditional role of providing a home for the farmer until 1984. Modern official records typically refer to the house as ‘Perching Manor Farmhouse’, presumably to distinguish it from the original medieval manor house whose remains lie beneath a nearby field, but the house has been known to locals as ‘Perching Manor’ for well over a hundred years (the 1861 census lists it as ‘Perching House’ whilst the subsequent nineteenth century censuses have it as ‘Manor House Perching’).

In a draft of the listing details written in 1947, or shortly thereafter, Anthony Dale FSA described the architecture as follows:

An L-shaped eighteenth century farmhouse, with Gothicized windows; two storeys and attic; five rooms wide; three dormers. Faced with square knapped flints with red brick window dressings, quoins, stringcourses, modillion eaves course and panels between the ground and first floor windows. Tiled roof. Windows with segmental heads and pointed Gothic glazing. The dormers contain casement windows and have artificial depressed heads which have Gothic panes in the sash windows below. Doorway with pilasters, projecting cornice, fanlight glazed with same pattern as the windows and door of six moulded panels.

[Howe 1958, pages 32-33]

The front (east) elevation is of a different design to the back (west), which suggests that the front of the house was extended in the late eighteenth century. A beam, believed to be a chimney beam salvaged from the medieval manor house, is now located over the fireplace in the kitchen. The interior of the house has been modernised but, as can be seen from the illustrations above and below, the exterior has barely changed over the years for which we have a photographic record. In the 1990s, a separate building, which houses a swimming pool, was built in the north east corner of the property where once a rhubarb bed flourished.

In 1835, Nathaniel Blaker took over the tenancy of the farm from Richard Marchant, whose family had lived in the parish for more than a century, and moved from Selmeston to Perching Manor with his wife Elizabeth and their infant son. The son, Nathaniel Paine Blaker [NPB] was to become a distinguished surgeon and, late in life, the author of a memoir that has much to say about life in Fulking in the middle of the nineteenth century. The 1841 census reveals that the Blakers had five servants at that time, more than any other family in the parish. Among them was Charlotte Paine, aged 13, who was NPB’s nanny. The household is much the same ten years later although Elizabeth’s widowed mother has joined them. The five servants then include a cook and a groom but the nanny is gone — NPB is sixteen. He tells the following anecdote about his father:

Among other things, my father had learned to “hold plough”, a not very easy accomplishment, as anyone not accustomed to it is likely to find by receiving a blow in the face from the plough handles. One day he had occasion to find fault with the carter for not ploughing the ground properly. The man replied: “Then you’d better do it yourself”. My father answered: “Stand aside and I will”. He ploughed one or two furrows, and handed back the plough to the man, who remained with him, an excellent servant, for fourteen years, and died in the Sussex County Hospital, when I was House Surgeon. [Blaker 1919, pages 1-2]

One of the jobs that came with being lord of the manor was that of ‘way warden’ — responsibility for the maintenance of the local roads. And with this job came controversy. In 1843, Nathaniel Blaker was summoned to court following a complaint from a Woodmancote resident that he was failing to maintain Holmbush Lane (now known as Bramlands Lane). He immediately called a ratepayer’s meeting at the Shepherd & Dog. The meeting decided that “the attempt to make the Hamlet of Fulking repair any part of the Holmbush Lane should be resisted”. It was resisted and, in due course, the matter was resolved in Fulking’s favour [Howe 1958, page 29].

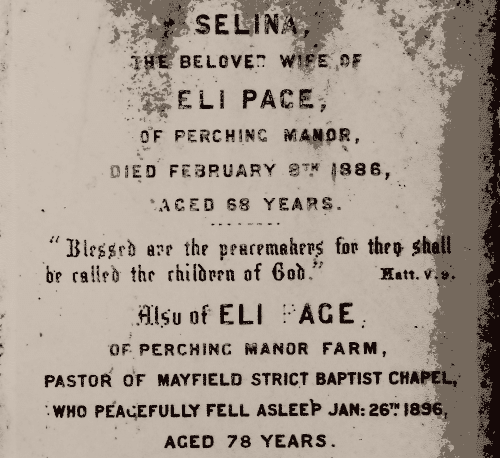

The Blakers left Perching Manor in 1856 or 1857 and Eli and Selina Page became the tenants of house and the farm. Eli Page is recorded as way warden in 1857. The Pages were in their late 30s at that time. The 1861 census records the family as consisting of four daughters, a son Richard, and Selina’s 80 year old widowed mother. No servants are listed. By 1871, Selina is listed as ‘farmer’ and head of family. The household then consists of three daughters, the youngest son Naphtali (Nap), who had been born at the farm in 1862, a granddaughter, a governess, a male domestic servant, and a visiting drapers assistant. Richard has married and is farming elsewhere in the parish. By 1881, the draper’s assistant, now listed as ‘draper’, has married Mary, one of the Page daughters, and is living at the manor with his wife and child. Selina is still the head of the household which comprises Nap (then 18), two other adult daughters, two other granddaughters, and a further child. There are no servants. Selina died in 1886, and by 1891, her family has left and Perching Manor is in the hands of Jemima Page, 62, living with a single female servant. Nap has married and is farming elsewhere in the parish. Jemima was not one of Selina’s daughters — she derived her surname through marriage to a Page. She does not appear in any of the earlier Edburton census records. She was, perhaps, a sister-in-law to Eli. Eli himself died in 1896. As pastor of the Mayfield Baptist chapel, he may have been living near there.

In 1901, Nap Page took over running the estate.

Nap was named after one of the twelve tribes of Israel [Naphtali], his father being a baptist minister. As a young man he was inclined to wildness, and was said to have ridden on horseback down Devil’s Dyke for a wager. He also rode regularly to his cousin John Page at Lodge Farm, Ringmer, for all-night card sessions. Rather than stick to the roads, he would go across the fields, jumping the hedges. Several photos survive of Nap. One shows him with a hen on his knee — this was Chuckles who was supposed to have laid an egg for Nap in his bedroom each morning. Another photo shows him in a long coat and bowler hat supervising the annual sheep shearing, sometime before 1912. A further photo shows Nap’s funeral procession leaving for Edburton church, with his favourite horse following behind the bier.

[Wales 1999, page 109]

William Beard, who had known Nap when he was a young man, recollected that:

It was sometimes said by older men that Nap Page was not as good a farmer as his father, Eli, but all who knew him agreed that there was no more jovial or generous host than the Squire of Perching Manor. His rather early death was greatly deplored! His passing marked the end of a period — the Horse Age. [Beard 1954]

As this quotation suggests, Nap adopted the role of country squire, becoming a keen huntsman and entertaining in a lavish style. Unfortunately, his interest in farming was minimal and by the time he died in 1920, the farm had become badly neglected.

In 1920, Henry Harris, an experienced and well-respected farmer, took over the tenancy of Perching Manor and the farm and gradually returned the land to good heart. Thus, for example, his sons recalled having to remove couch grass from the upper parts of the Downs for many years. Henry became Chairman of the Parish Council, was instrumental in having the telephone service extended from Poynings to Fulking, and arranged for the Southdown bus service to be routed through the village. During the war he was the Home Guard sergeant for Fulking and later became officer in charge. In the early years, his 800 acre farm employed a workforce of 16 men and a dozen horses to tend 1000 Border Leicester sheep, 60 milking cows, a small herd of pigs and some 30 acres of arable land growing a mixed crop of wheat, flax, oats (for the horses) and barley (for the pigs). The remaining acreage was grazing pasture for cows and sheep, along with a market garden growing potatoes and onions.

During the war, a team of land girls came in for the harvests and the male workforce included two German and three Italian PoWs, the latter being billeted in the cellar at Perching Manor. The PoWs were repatriated in 1947 and 1948 and replaced by two displaced persons from Latvia. From around 1938 on, the farm acquired tractors and these rapidly displaced the horses and halved the workforce. After the war, three combine harvesters were purchased. During the 1950s, the farm holdings expanded to more than 2000 acres including 1000 acres for grain, 1000 sheep, and 250 cows bred for beef. When Henry Harris died in 1961, aged 72, his sons initially continued to run the farm as tenants of the Crown before Brian Harris took sole charge. In 1984, the Crown broke up the estate. The farm was sold to the National Freight Corporation and Perching Manor itself, which had always been the main farmhouse and the home of the farmer, was sold as a separate lot to the Dubrey family. The house remains in private ownership.

Tony Brooks

References

- William Beard (1954) Glimpses of past personalities. St. Andrews Quarterly 24.

- Nathaniel Paine Blaker (1919) Sussex in Bygone Days. Hove: Combridges.

- F.A. Howe (1958) A Chronicle of Edburton and Fulking in the County of Sussex. Crawley: Hubners Ltd.

- Tony Wales (1999) The West Sussex Village Book. Newbury: Countryside Books.

[Copyright © 2013, Anthony R. Brooks. Adapted from Anthony R. Brooks (2008) The Changing Times of Fulking & Edburton. Chichester: RPM Print & Design, pages 191-193.]

Currently popular local history posts:

“A Thriving Living Landscape”

The South Downs National Park Authority has issued a draft policy document [PDF], entitled A Thriving Living Landscape. and invited comments. Some extracts follow:

- The National Park offers important opportunities for renewable energy generation including woodfuels, solar, wind and anaerobic digestion ..

- Climate change or lack of appropriate management could be a threat to much of our heritage.

- Allow the landscape to continue to evolve and become more resilient to climate change.

- Contribute to the delivery of government climate change strategy targets through renewable energy schemes ..

- There are five oil and gas wells within the Park some already in production others at the exploration and appraisal stage.

- The South Downs National Park carbon footprint relating to transport is a significant proportion of the overall total .. promoting alternatives to the car also supports opportunities to make tourism more sustainable and increase spend per person (surveys show this is a fact) ..

- Promote travel behaviour-change across the National Park ..

- Increasing the proportion of visitors staying in the Downs .. develop .. a wide range of high quality accommodation provision ..

- Most problems with visitor behaviour are local visits from surrounding areas ..

- Volunteers are not widely representative of the local demographic.

- Increase opportunities for young adults, people from Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) communities, people with disabilities and people from areas of deprivation to visit the National Park.

- Support land managers to access incentive schemes and work with partners to effectively target agri-environment grants and influence the development of future payment schemes.

- With the removal of the Regional Development Agencies (RDA’s) and setting up of Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs) the economic framework of the region has changed significantly. There are three LEPs that cover the SDNP. LEPs currently administer the Growing Places Funds which are revolving funds aimed at unblocking development proposals. Currently no Rural Growth Funds are available within the South East LEPs. It is likely that the LEPs may have an enhanced role in distribution of EU structural funds. Future investments will need to fit with the LEPs Strategies for Growth. There is a need to ensure that these have a rural element and that they fit with SDNP objectives.