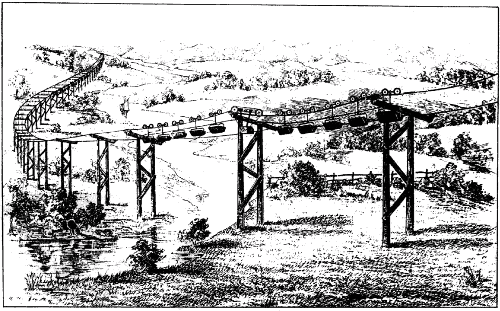

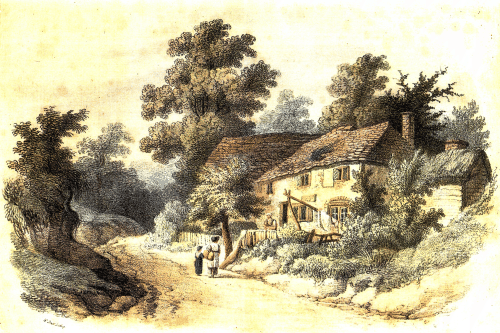

The building in the 1780s: a lithograph by W. Scott after a painting attributed to William Henry Pyne (aka Peter Pasquin)

Sussex was renowned for smuggling in the early nineteenth century (Blaker has a brief chapter on the topic) and the pub was used to store contraband. It seems that the goods were first taken up the outside steps and then lowered through a concealed opening into a large cavity below. The location of this hiding place is not currently known, although there is anecdotal evidence that it may have been incorporated in structural changes made to the pub over the course of time. A reporter from a local newspaper is thought to have been shown it in 1927, so there may still be a large chamber waiting to be found — complete with a keg of brandy.

During the 1930s, the landlord was Eugene Baldey, whose father was known for running a rather dubious shoot and who was often seen selling game or rabbits at the back of the pub. The pub in those days consisted of two bars: the public and the saloon. The public bar had sawdust on the floor as the farm workers and locals usually came in wearing muddy shoes or boots. The saloon bar was carpeted and used by visitors and the local gentry. It was separated from the public bar by a wall with a serving hatch in it. All drinks were dispensed from the public bar and when someone in the saloon wanted a drink they knocked on the hatch, placed their order and it would then be passed through to them. It was often the case that the same drink in the saloon bar cost a penny more than in the public bar. Lemonade was made on the premises up to 1939, a practice that was resumed for a while after the end of WWII, and the pub’s own cider was legendary. Along with this, children could go to a small window beside the front door, known as the Bottle and Jug and buy a biscuit for a halfpenny. In the 1930s, the young Geoffrey Harris used to buy ten Gold Flake cigarettes for his father, Henry Harris, from the window. These cost sixpence and the kindly landlord would always give him a chocolate biscuit.

After the war Captain Cyril Watts, a Canadian Officer who had been previously billeted in the village for the D Day Invasion, returned to the village and took over as landlord, assisted by his wife Kay and sister-in-law Joyce. Cyril was a colourful character. There are stories of him leaning out of one of the upper windows on occasions clad only in pyjamas, shouting at the full moon. Another time, having discovered his wife was having an affair, he hung from an upstairs window until he fell although, as it turns out, he did not injure himself. This was considered to be sufficiently noteworthy to be reported in the News of the World. Later, he was accused of bigamy.

The BBC filmed Morris dancers at the Shepherd and Dog in 1945. A photograph taken at the same event was published in

The Times and featured in the newspaper’s calendar the following year.

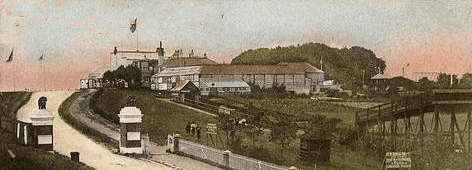

The Hunt Meet outside the Shepherd and Dog in 1946. They used to meet there every year but an anti-hunting landlord later discouraged it and the hunt moved to the Royal Oak in Poynings where the meet has become a well established tradition.

During the 1950s and into the 1960s, Bill Hollingdale, the village poet and a well known local character, would often recite poetry in the pub for entertainment. The cue for his party-piece was when a young man came into the pub with his girlfriend. Bill would lose no time in making himself known to the couple and on finding out the young lady’s name, he would then quickly adapt a suitable piece of poetry to include it and then recite it to her in a very loud voice to a now silent pub. Being flattered by this attention the girl would insist that her boyfriend should at least buy Bill a pint. He earned quite a few pints this way.

In 1964 Bob Cruickshank–Smith and his wife Ruby took over as landlords and, in 1965, invited Geoffrey Harris’s firm Springs Smoked Salmon to start serving cold lunches with salad, offering a choice of smoked salmon, trout, pheasant, partridge, and chicken. This was highly successful but had to be discontinued the following year as the main smoked salmon business was expanding so fast they were unable to maintain a regular supply to the pub. By now the structure of the brewery industry was starting to change. Small, privately owned pubs were gradually being bought up and combined into small groups, usually by a brewery, which meant that landlords were now tenants rather than freeholders. The Shepherd and Dog became part of these changes and when Tamplins brewery bought it, Bob and Ruby moved on. Stan Liquorish took over until the mid 1970s with his wife Joan. He was a popular and successful landlord whose deputy, Stan Taylor, later became the landlord of The Plough at Henfield.From the mid 1970s until the 1990s, Tony Bradley-Hole took over the Shepherd and Dog. In 1978, at the time of the Queen’s Silver Jubilee, a fancy dress parade for children took place along The Street in Fulking, finishing with a tea party for the entire village in the pub car park, hosted by the Bradley-Holes. Later that year the pub also organised a torchlight procession through the village which culminated in a bonfire and firework display, on what is today, the front lawn of Cannonberries on the Poynings Road. Similarly, for the wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer, the pub offered breakfast to start the day. Villagers then went home to watch the ceremony on television and returned to the pub afterwards for food, drink and a celebration that lasted until midnight. Tony Bradley-Hole was followed by a succession of landlords and during this time it seemed that as soon as a new landlord had built up a good reputation for food, service and a warm welcome at the Shepherd and Dog, the lease would be sold on. There would then follow a slight fall in the pub’s popularity while the next landlord, possibly with a different approach to the business, built up trade again. In January 2006, Geoff Moseley and Jenny Tooley purchased the lease of the pub from Badger, an independent family brewery operated by Hall and Woodhouse, and initiated a major refurbishment.

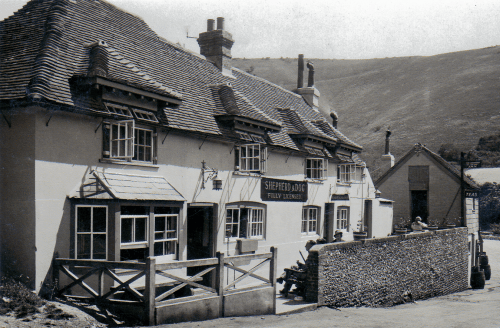

The Shepherd and Dog comprises two Grade II listed buildings. The main building is timber framed, has two storeys wholly faced with stucco, sits on a chalk terrace above the road, and dates from the seventeenth century or earlier. It has a hipped tile roof and casement windows, a bay window on the ground floor, and four hipped dormers on the first floor. The dormers are twentieth century and date from the interwar years. The adjacent stables also has two storeys and casement windows but dates from the eighteenth century. The first floor is slate hung and the ground floor stucco.

Tony Brooks

References

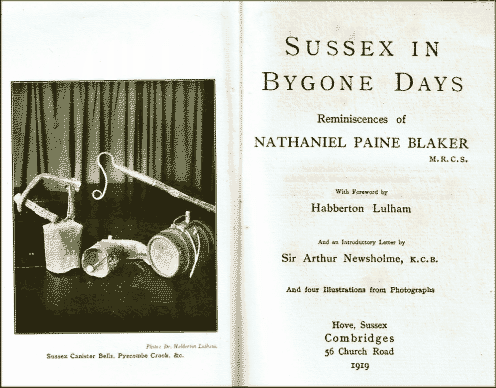

- Nathaniel Paine Blaker (1919) Sussex in Bygone Days. Hove: Combridges.

- Peter Holtham (2004) “The brewers of West Sussex”. Sussex Industrial History 34, 2-11, PDF.

[Copyright © 2013, Anthony R. Brooks. Adapted and condensed from Anthony R. Brooks (2008) The Changing Times of Fulking & Edburton. Chichester: RPM Print & Design, pages 9-18.]

Currently popular local history posts: