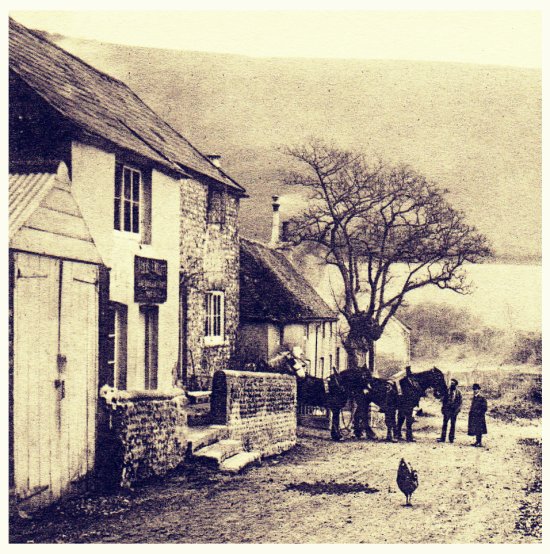

Fulking Post Office as it was around 1900 soon after the proprietor, Edward Willett, had moved the franchise there from its previous location adjacent to the Shepherd & Dog. The sign above the door describes the shop as a “family grocer, draper and baker”. Note the Nestle’s Milk hoarding to the left of the door and the brick pillar Post Office letter box to the immediate right. The building to the right is the Old Farmhouse.

The Old Post Office, as it is now known, is a Grade II listed house in the centre of Fulking. The current house comprises two cottages. The newer cottage was built straight on to the front of the older cottage and is thus the part that one sees from the road today. The cottage at the rear is much older and may date back four centuries. In the garden behind the house are the ruins of a third old cottage which was destroyed by fire in the 1920s. Also behind the house is an old bakehouse together with a large, brick built, underground water tank. The latter was used to store water for the bakery. It was filled from

the village water supply system and the supply valve is still situated in the tank. The house shares a wall with its neighbour,

the Old Farmhouse. The two houses were originally separate but, at some point, the roof of the Old Farmhouse was extended west and thus the two houses became attached. There was once even a communicating door between the two houses. These changes presumably date from the period in the nineteenth century when both buildings were occupied by the Stevens family (see below).

In 1851 and 1861, the shop was run as a grocers by the Welling family (William Welling was also a builder). By 1871 the shop had passed into the hands of Charles and Orpha Mitchell, a young couple who ran it as a grocers and drapers with the aid of an assistant. Throughout this entire period, the Old Farmhouse had been in the hands of the Stevens family. In 1881, Emily Graimes (née Stevens), a widow, and her sister Susannah Stevens, were running a grocery, bakery and drapers shop in the adjacent building. By 1891, the shop had passed into the hands of young siblings Joseph and Elizabeth Newman. During all of this period since 1851, there had been two shops in Fulking, the other one being the Bake House, Corn Store & Post Office owned by Edward Willett and located next to the Shepherd and Dog in a house that is now called the Old Bakehouse. Some time after 1891, Edward Willett closed his own premises and took over his competitor’s. The new Willett enterprise combined the roles of grocer, draper, baker and post office in a single shop.

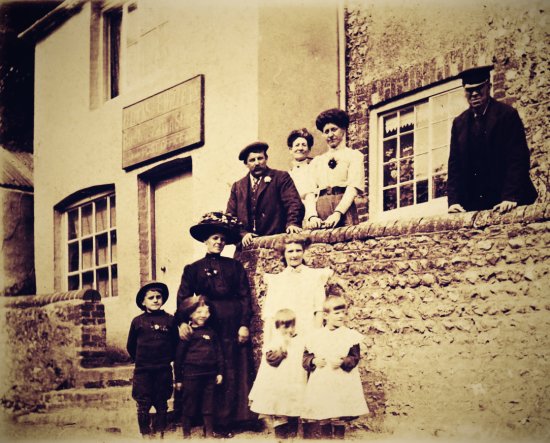

A postcard showing Fulking Post Office in the very early years of the twentieth century. Note the addition of the bay display window. It is likely that Obadiah and Rhoda Lucas are the couple in the photograph, together with their son James who was born in 1892. James was to die in France in 1916 and his name is recorded on the war memorial in the church in Edburton.

Edward Willett died in 1905, aged 81, the year after his wife. By then Fulking Post Office, as the shop was known, had passed into the hands of his daughter Rhoda and her husband Obadiah Lucas. They had married in 1891 when Rhoda was 30 and Obadiah 22. Obadiah’s father, also called Obadiah, had worked for Edward Willett when the latter’s shop had been in its original location, as had Rhoda herself. Rhoda’s husband was also a shop assistant by trade but he had been working in Brighton at least until the time of his marriage.

A Lucas Stores, Fulking & Beeding delivery van from the early 1900s, probably an Albion. Albion vans were built in Scotland and had a reputation for reliability. Harrods ran a fleet of them.

Frank Lucas, a relative of Obadiah’s, was the proprietor of a grocery and provisions store in Upper Beeding. The Fulking and Upper Beeding shops adopted the name ‘Lucas Stores’ and operated in tandem with shared delivery vans. The vans were garaged one behind the other, in a long narrow building that is still situated beside Jasmin Cottage on the opposite side of the road to the shop. A bulk paraffin tank, used to fill up customers’ containers, was installed at the back of this garage.

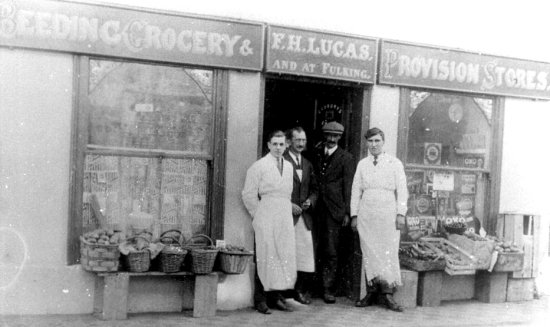

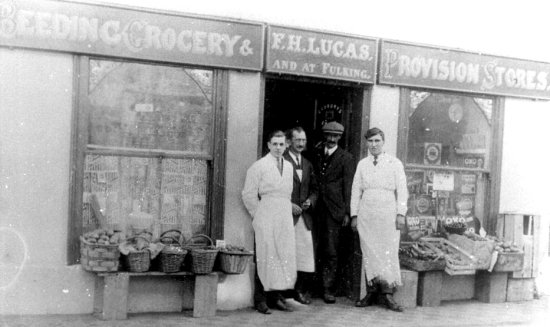

Beeding Grocery & Provision Stores, proprietor F.H. (Frank) Lucas

Beeding Grocery & Provision Stores, proprietor F.H. (Frank) LucasAs time went on Lucas Stores expanded to include Lucas General Stores at the Post House in Small Dole and a branch in Bolney run by Fred Lucas (also a relative). Since the Fulking store included a bakery, it supplied bread to the other shops. The shops prospered. Obadiah himself died in 1930 aged 61. It is possible that Rhoda ran the Fulking store by herself for a time but, by some time in the mid-1930s, Obadiah’s younger son Percy had taken over.

A Lucas Stores, Grocer & Baker Model T Ford delivery van c1920, outside the Fulking shop. The man on the right is Obadiah’s younger son, Percy.

Ken Browne, who was born at the Dyke Hotel and later lived in Yew Tree Cottage, recalled working for Percy at the shop between 1937 and 1939. His duties included serving in the shop, delivering bread, and collecting orders. Percy inspected his staff every morning before they started work, to check that they had clean, white aprons on and that their hands and fingernails were well scrubbed. Two men worked in the bakery, two more in the shop and two drove the vans – one for the area north of the village and the other for the south – delivering bread and groceries and collecting orders that Percy would then deliver personally the following day. In addition to this, other local deliveries were made on a bicycle.

In their heyday, probably during the 1930s, the Fulking and Small Dole shops employed nine men full-time and sold almost everything that local people needed. During the Second World War, business was sustained by the government rationing programme. Because there were relatively few cars and petrol was strictly rationed, people shopped locally and village shops thrived.

In addition to being a shrewd businessman, Percy was popular and well respected and those who knew him spoke highly of him. Whenever possible he was prepared to help his customers by allowing them credit until pay-day, cooking special cakes (including Christmas cakes) in the bread oven when it was not in use, and even cooking turkeys and puddings for customers at Christmas.

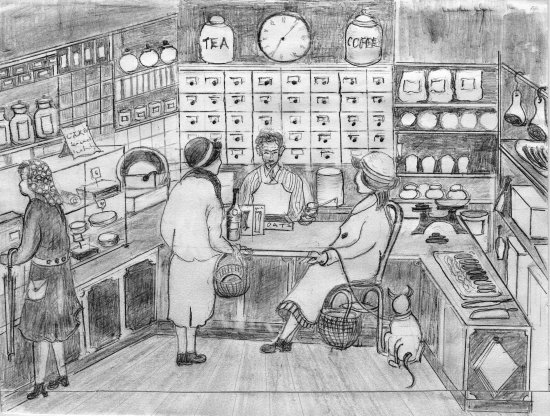

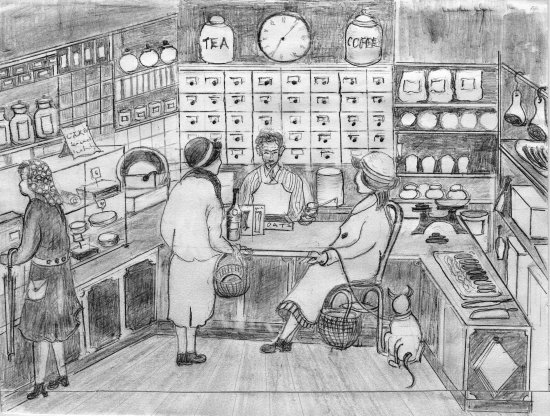

A crude but informative drawing by George Ridge showing the interior of the shop in the Percy Lucas era

During the 1950s, the development of large grocery chains, such as

Sainsbury’s,

Home and Colonial and

International Stores began to have an impact on village shops. Running a car was becoming more affordable and people were thus able to shop further afield. Percy recognised this and sold the shop in the 1960s.

Ownership then passed through several hands until Robin and Marlene Howarth purchased the premises in 1972. They made some major changes, including demolishing a flint stable in the back garden and replacing it with a tearoom. However they were refused planning permission for a two-storey guest accommodation extension. Nevertheless, the tearoom was a great success. The profits were augmented by a modest income from the shop and post office and the business as a whole provided seasonal employment for several people from the village. In the 1980s the shop passed into the hands of Ted Croxton and his wife but business had started to decline and the property was once again put on the market.

In 1985 Gill and Stuart Milner purchased the shop. The tearoom was closed and the shop concentrated on running the small post office and selling mainly local Sussex produce including fresh baked bread, honey, vegetables, free range eggs and Horton’s ice cream as well as sweets, groceries and frozen food. Later a range of art, crafts, aerial photographs taken by a local pilot, clocks repaired by a local resident, small antiques and antique books was added to the stock, along with a selection of maps and postcards. Also on sale, of special interest for visitors to the village, was a small guide, entitled A Walk Down The Street, written and published by Stuart Milner.

Fulking Post Office Stores as it was in the early 1990s shortly before it closed and returned to being a private house after well over a century as a shop. It looks very little different today but a red Post Office letter box outside on the garden wall by the road serves as a reminder of the role that it once played in village life.

The severe winter of 1987 brought a heavy snowfall to Fulking and the village was cut off for 3 days. The shop suddenly became alive with eager customers. Eventually, however, it was no longer economic to keep the village shop open and it closed in 1995. The building was converted to residential use and renamed “The Old Post Office”. The area that was the original shop floor has been retained as one large, long room and the tea room and original 1900s bakery areas also remain largely unchanged. The exterior façade of the building has been preserved and still appears much as it does on old postcards of Fulking.

Tony Brooks

Listing details:

The Post Office Stores and house attached to the east. One building. Early Clg. Two storeys. Three windows. Faced with cobbles on first brick dressings, quoins and stringcourse. Slate roof. Glazing bars intact on first floor. Projecting shop window on west half of ground floor.

[Copyright © 2013, Anthony R. Brooks. Adapted from Anthony R. Brooks (2008) The Changing Times of Fulking & Edburton. Chichester: RPM Print & Design, pages 38-46, 159-159, 420.]

Updated with corrections in June 2015.

Currently popular local history posts: