[The essay that follows was written by the Reverend Hugh B. Simeon who was Rector of Edburton from 1928 until 1936.]

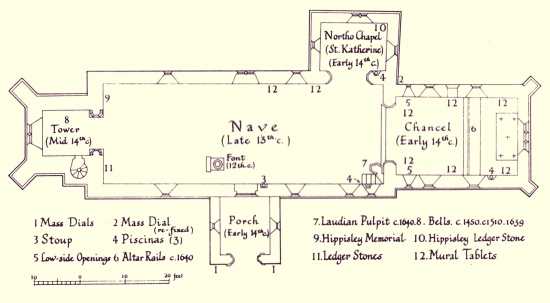

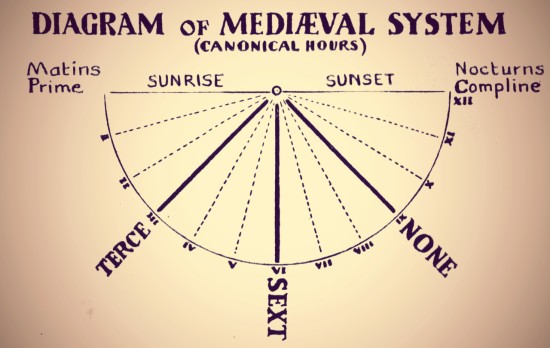

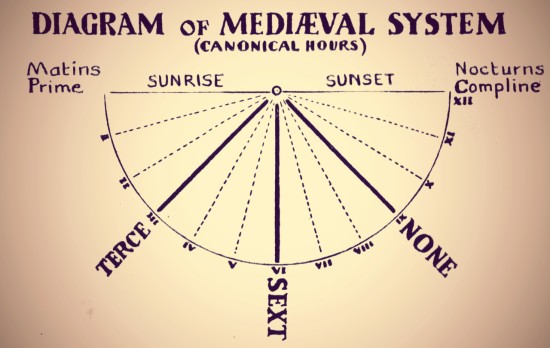

There are four mass-clocks on the Church, three on the South side, and one on the North side. A mass-clock is a sun-dial cut vertically on an outside wall of the Church. It is a circle made by one line, or sometimes two lines, with a hole in the centre. In some this hole has been filled up with cement, projecting from which there was once a metal rod, called a gnomon or style, the shadow of which cast by the sun passing across the sky rested upon lines cut on the dial. In Saxon and Norman times, when there were no clocks and watches, these mass-clocks or sun-dials were used for marking the times of services, and also for secular purposes. They are to be found on Saxon, Norman and early English churches.

The existing church at Edburton, with exception of the tower which is of late fourteenth century work, was built in what is called the transition period, when Norman architecture was beginning to give way to early English, about the end of the twelfth century. The year 1180 has been given as the date; it was, however, probably twenty or thirty years later than that. But on the site of the Church there had stood a Saxon church, built about 930 or 940, by the Princess Eadburh, daughter of King Eadward the Elder, who succeeded to the throne of England in 901, upon the death of his father, King Alfred the Great. She converted to Christianity the Pagan Saxons living here and built a church for them and gave her name to the place, Edburhton.

If these mass-clocks are Saxon, they must be about 1,000 years old, and they have all suffered in various degrees from the ravages of time. The best preserved one on the South side is on an outside comer stone of the East wall of the porch, facing South, and about six feet from the ground. The metal gnomon has long since disappeared, and there is not a single original gnomon existing in situ in the country. The hole has been filled in with cement. The double circle of incised lines and little holes can be clearly seen, and the lower half of the dial is divided into two equal parts by the line which marks the hour of noon, each part being divided by five lines into six equal parts, the whole dial thus showing twelve hours from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. The lines on the Western (or left) ide of the noon line mark the morning hours, and those on the Eastern (or right) ide the afternoon hours. At the end of the upper Western line is clearly seen a cross.

On June 21st (the longest day of the year) the sun rises a little before 4 a.m. (Greenwich time, not Summer time) considerably North of East, and as it cannot cast a shadow round the comer of the church, the first shadow that can be cast is at (approximately) 6 a.m., as about two hours elapse before the sun is due East. As the Midsummer Mass was in ancient days one of the chief services of the year to which everyone went, and was held soon after daybreak, this hour was marked with a cross known as a “rnaes-dael”, which means “mass time”.

Just below the mass-clock is another, which is much more weather worn, but the lines of the circle and the lines on each side of the noon- line can be seen. These are more distinct on a sunny morning in summer. In this case each quarter of the lower half of the dial appears to be divided into four parts by three lines.

On the corresponding comer stone on the West side of the porch can be seen another mass-clock. The gnomon hole has not been filled up, and the remains of the old metal gnomon can be seen about a quarter of an inch deep in the hole. The best place from which to see this mass-clock is the junction of the church path with the path to the new part of the churchyard to the West.

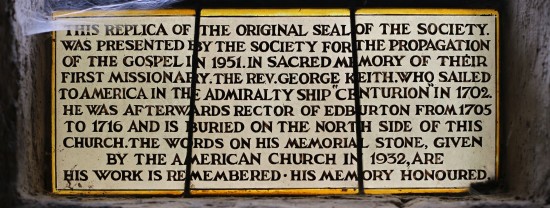

Re-used stone on the north side of the church.

The grooves were probably made by archers sharpening their arrows.

The fourth, and perhaps the most interesting of the four mass-clocks, is to be seen on the North side of the church, on the lowest stone on the right, or western side, of the low chancel window. It is on the wrong side of the church, where no sun ray can reach it. It is also upside down, and one-half of the stone has been cut away to fit the other stones, so that there is only two left of what should be the afternoon lines. This seems to show that the stone is part of the old Saxon church, and that the builder who placed it in its present position did not know what it was. If this supposition is correct, it would seem to show that all the outside stones of the present church other than (perhaps) the flints or any stone subsequently used for repairs, formed part of the old Saxon church.

It is also interesting to note that the arch of this particular window, and also the arch of the corresponding window on the South side, is of one stone, and is not composed of two stones placed together, probably therefore it is a stone of an earlier period. This mass-clock is the best preserved of all the four. The lines are very clear, and the space between the lines are of different widths. The spaces between the lines do not represent hours but periods of time, which would probably have nothing to do with church services.

It was probably the business of one man to ring the church bell when the shadow of the gnomon touched each Iine. In those ancient days, when there were but few means of artificial light, other than rushes dipped in fat, the rustic people would rise at daybreak and go to bed at sunset. The two lower divisions mark the time of rising and morning work. At Lady Day and at Midsummer, and at Michaelmas, the first shadow that could be cast is about 6 a.m., and at Christmas about 8 a.m. The bell would be rung according to the season, for the people to rise, and have breakfast, and go out to work. The third division represents by measurement sixty minutes, and the bell rung when the shadow touched the third line would call them in to dinner, and sixty minutes later, when the shadow touched the next line, would send them out to work again. The very narrow division next the central or noon line represents by measurement seven minutes. This is the mid-day Angelus, and all work would instantly cease when the bell rang. The men and women would stand (or in dry weather kneel) together and say the Angelus prayers, until at the end of the seven minutes the bell would ring to close the Angelus, when they would resume their work. Probably the central or noon line would signify nothing to them. It is noticeable that the third, or dinner, line is exactly half the whole space between the first line and the noon line. This is the likely meaning of these divisions.

Jean-Francois Millet L’Angélus (1857-59)

Hugh B. Simeon