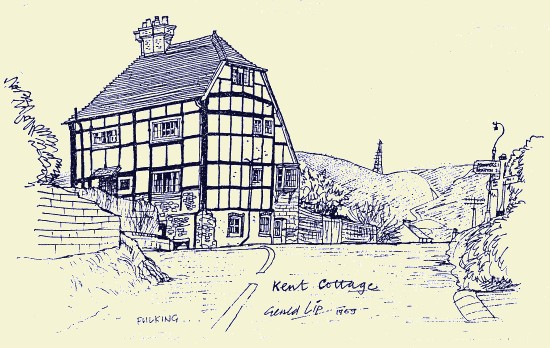

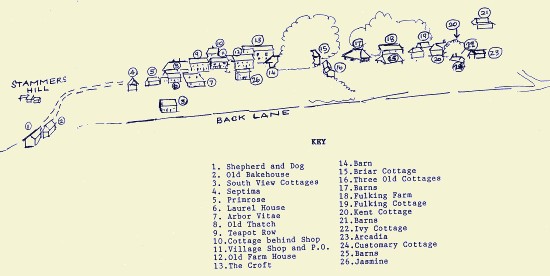

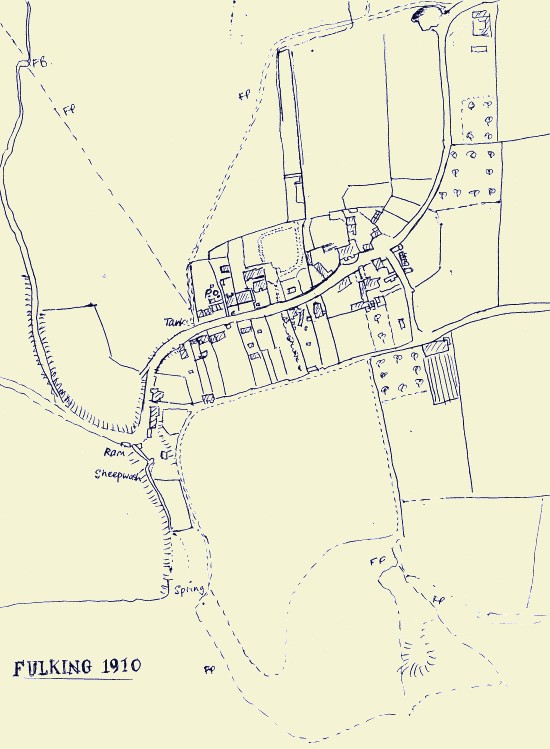

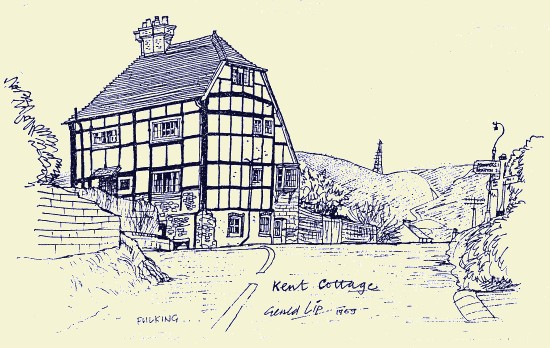

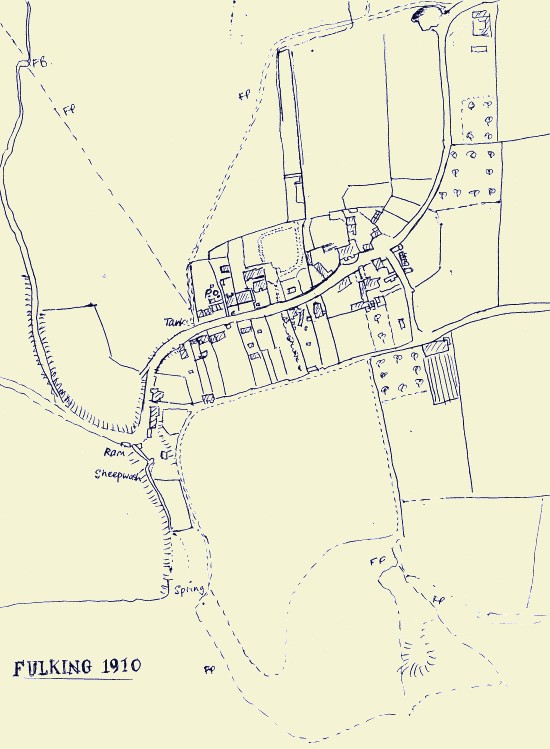

This document is a web page transcription of a sixteen page pamphlet written by the late Stuart Milner in 1987. It was originally sold in Fulking Village Shop which his wife Gill ran at that time. The transition to the web has entailed some minor adjustments to the images but the text has been left exactly as it was. It is now some thirty years old and a few remarks, such as those relating to the Montessori school and the use of the Chapel, are no longer of contemporary relevance. The opening illustration is by Gerald Lip and was originally published in The Argus, probably in 1969. Subsequent drawings are by Stuart Milner, as are the house photographs. The final section comprises postcards of Fulking from the 1895-1935 period together with a couple of maps of The Street.

Fulking is the site of an ancient settlement and dates from the earliest days when nomadic tribes settled where water was plentiful and land fertile. Many examples of implements used by these early farmers have been discovered and are on view in Brighton Museum. By the time the Domesday record was made in 1086 Fulking was a well-established farming settlement: “It vouched for three hides and one rod. Six villeins are there with two ploughs”. This indicated a farming area of about 340 acres with six tenant farmers. The name of the village probably derives from the early settlers ‘the people of the Folc’ In the Domesday Book it is mentioned under the name of Fochinges. In the 13th century it was called Folkynge, in the 14th century Fulkyng.

In 1984 in recognition of the village’s architectural interest the Department of the Environment designated the section of the village described in the following walk as a conservation area. But wherever one goes the Downs form an imposing backdrop and it is the combination of scenery of outstanding natural beauty and varied and old buildings which gives Fulking the charm and mellowness which is so attractive to visitors.

Let us begin at Kent Cottage where Fulking’s old North-South routeway (Clappers Lane) joins the equally old East-West route — The Street.

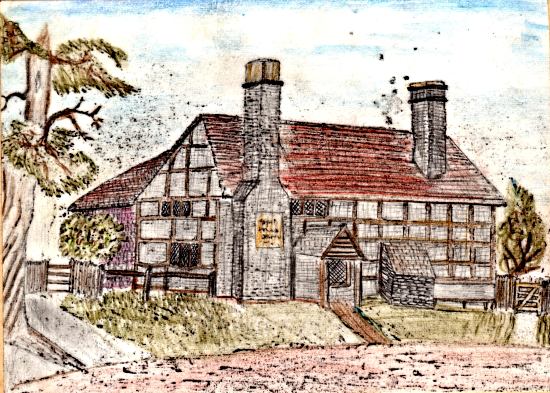

Kent Cottage is the striking, half-timbered, black and white building which stands prominently at the eastern end of the Street. It dates from around 1650 and was part of an original two-bay house of which only a bay and a half remain. Beside the road is a cellar or undercroft and above that a large parlour with an open fire-place with a cambered and stop-chamfered chimney beam. Jutting out over the road from the parlour is an outshut, today marked by a projecting window. Above the cellar are two tall storeys and overall a very large attic. The house is built on slightly rising ground and the back of the cellar is a solid wall of chalk on which rests an enormous beam which supports the timber framing for the floors above. The timber framing so noticeable on the outside does in fact hold the building together in a series of large braced panels. Around the turn of the century Kent House was used as a poor law infirmary or workhouse and before becoming a single residence was split into two cottages.

Next door is Chimney House which modestly screens its modern individuality behind a fine flint wall.

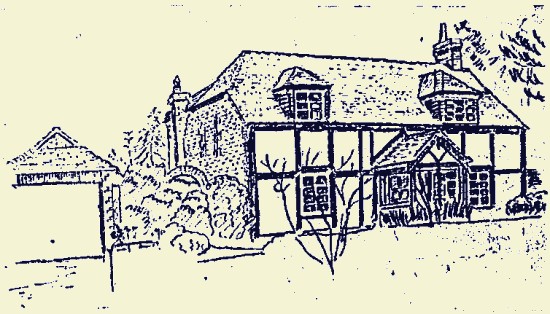

Opposite to Kent Cottage, and of the same period, is Fulking Farm House. This is a substantial building whose overall size is not apparent from the street. Its timber framing is hidden by an eighteenth century facade and as its name and size indicate it was once a very substantial farm property and remained a farm until relatively recently.

Fulking Cottage east of Fulking Farm House displays its timbers and is built on the site of a barn.

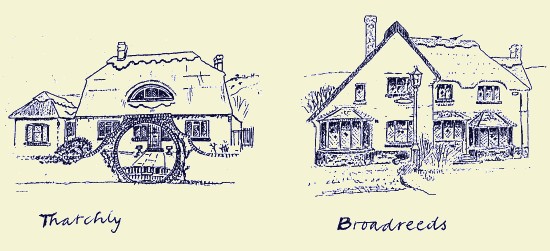

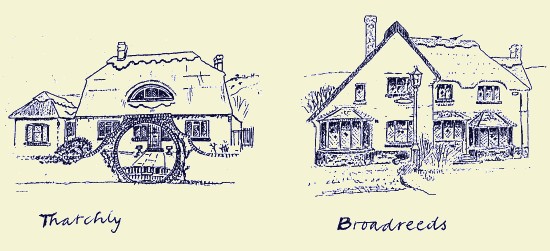

Further down from Kent Cottage and on the same side are two elegantly thatched houses. Thatchly has a circular gateway and Broadreeds has the pheasants on the roof. These two houses built around 1937 have obtained some distinction for they appear in an illustration in South Eastern Survey by Richard Wyndham as ‘Fancy homes at Fulking, Sussex’ published in 1940. The famous dust-jacket of this book is a painting of Fulking from the Downs with a farm wagon in the left foreground and farmworkers loading a hay wagon. All the dustjackets of the books in the Batsford series ‘The Face of Britain’ were illustrated by Brian Cook, who was also known as Brian Batsford, who used the ‘Jean Berte’ printing process to reproduce his flat but bold colours which made his work so distinctive.

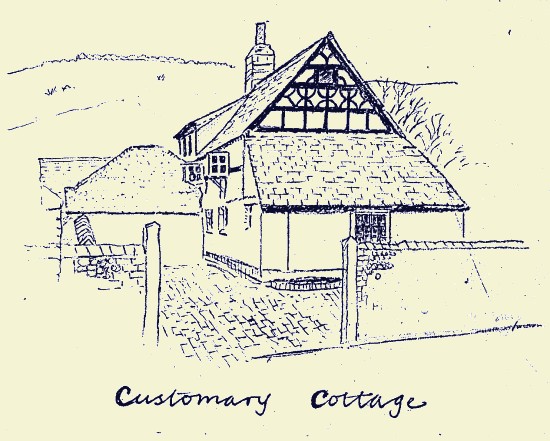

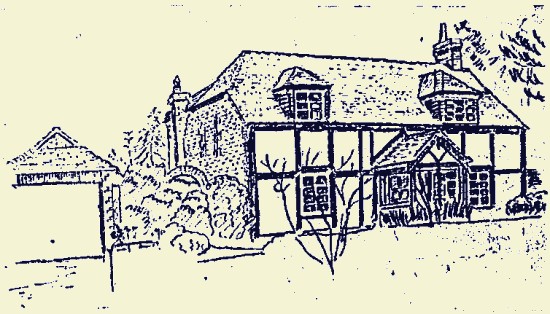

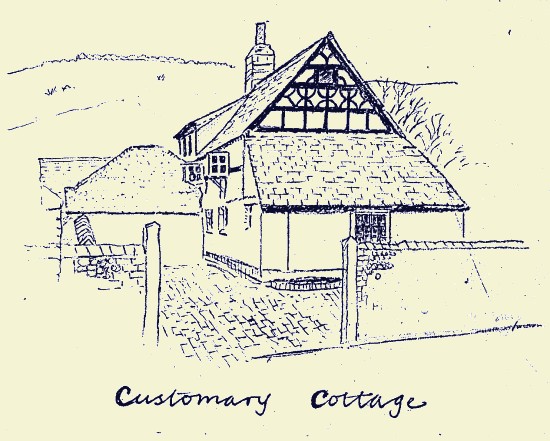

Next to these two comparatively modern houses is Customary Cottage. It was built late in the seventeenth century in flint, brick and timber and it is the ornamental black and white timber beams on the exposed gable-end which immediately catch the eye. The inside is rich in low ceilings and timber beams. The cottage has been put to a variety of uses over the years. At one time it was the communal wash house for the village, has been used as the District Office for the Registrar and Relieving Officer and used by the visiting doctor for his weekly surgeries.

The larger house standing beyond Customary Cottage is Fulking House. This was built in the early years of this century and stands on the site of three very ancient cottages.

Next door is Briar Cottage distinctive by its position onto the street. Early photographs show a small front garden indicating a gradual change in road width. One of the walls of the old cottages is still visible in the wall separating Briar Cottage and Fulking House.

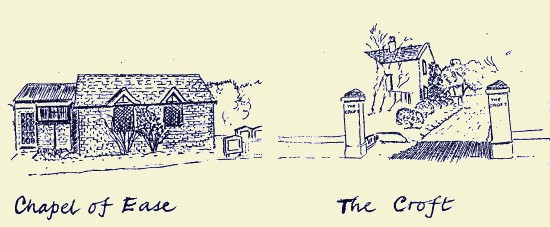

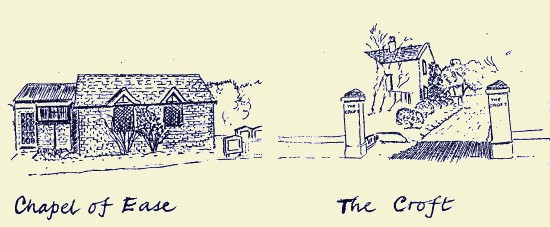

Next is Weald House built in the 1950s and then Jasmine lived in by the same family for much of this century. Opposite to Fulking House is a corrugated iron and brick building with a notice board outside which denotes it as the Village Hall. When villagers made their own entertainment it was well used by the local dramatic society and for other entertainments but is now mainly occupied by a Montessori school. Beside it stands the chapel built as a Chapel of Ease in 1925 now only used for a storeroom.

Beyond the chapel and behind tall white pillars is The Croft, a large white house which stands out prominently when the village is viewed from the hills. It is set well back from the road because it was built just before the turn of the century behind an old barn. Until 1984 this barn was run as a garage, taxi-service etc. Barn House, which stands in front of the The Croft, was built on the site of the barn.

Between The Croft and Fulking Farm House to the east are three houses built after World War II, which replaced barns. These are The Keep, Coombes and Glenesk.

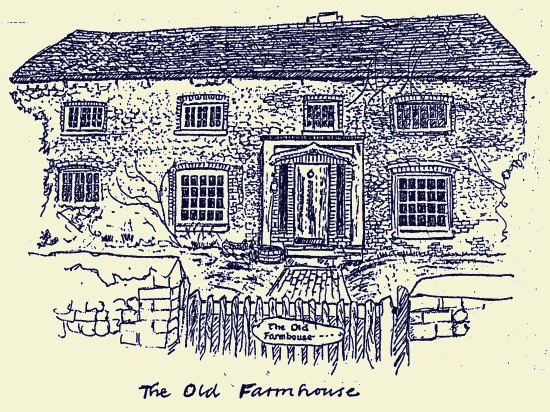

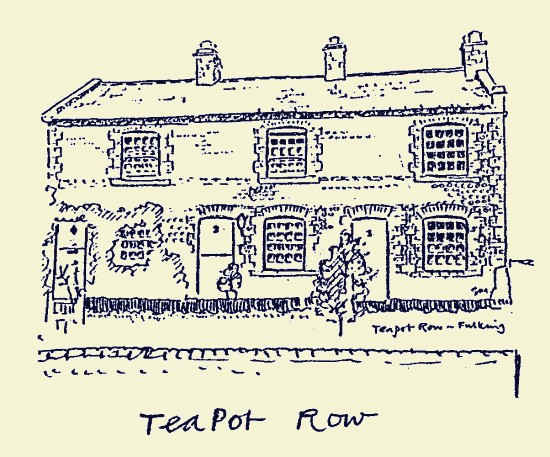

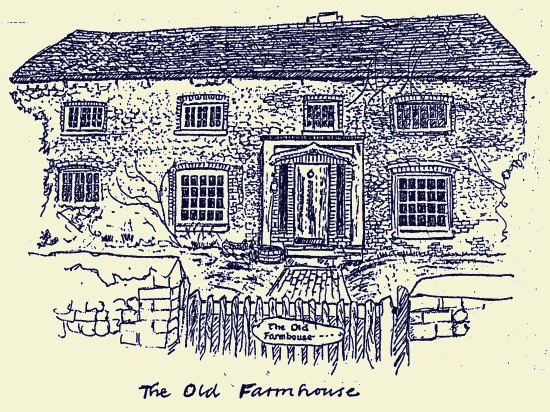

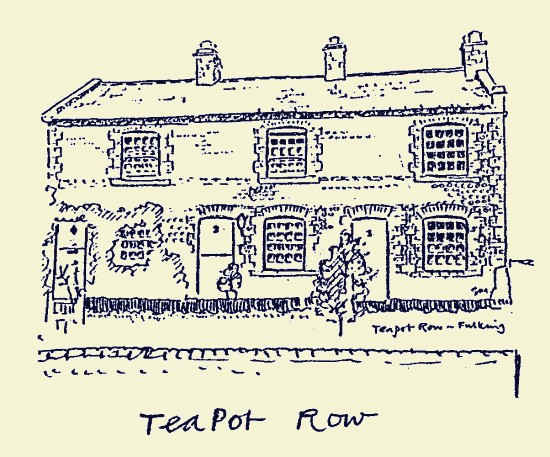

The only stone faced building in the village is The Old Farmhouse and is presumed to be the old manor house of the village. It probably dates back to the twelfth century and the brick mullioned windows on the east wall are undoubtedly sixteenth century. The manor once had a great hall running north behind the house and a portion of the wall still remains in the garden wall. The building has many massive oak beams and in a bedroom a beautiful adzed floor with broad oak planks polished by years of use. The roof once consisted of Horsham tiles which were removed in 1930. For many years the building was used as a tea-room and to attract business from the many walkers on the Downs it carried a large white painted teapot on the roof. As a consequence the row of three cottages beyond the village shop have always carried the name of Teapot Row.

Many stories and legends are told of The Old Farm House. Smugglers are said to have used the batch in the roof to pass brandy kegs through the shop premises next door. There is a little room where King Charles is said to have hidden on his flight to the coast. There is the inevitable ghost, a sweet little old lady dressed in black who carries a bible, and makes herself known to children. She also made herself known to a group of seventeen Canadian soldiers who were billeted there in 1941. Subsequently these men went all through the Italian campaigns and wrote to friends in Fulking that the old lady was with them whenever they went into action and that not one of them was wounded.

The tearooms were frequented by many writers and artists including H.V. and E.V. Morton, Ernest Raymond and Geoffery Farnol. It was in the tearoom in the course of a conversation about lamps versus electricity that Patrick Hamilton conceived of the idea for his play and film ‘Gaslight’.

The Village Shop next door is in reality two cottages, with the ruins of a third cottage in the garden which was built against the wall of the great hall previously referred to. The front building facing the road has an inscription on a beam in the cellar “Built by J. Brown in 1823”. The cottage behind is much older, possibly four hundred years old and the garden ruins older than that. Behind the shop is an old bakehouse and underground a very large water tank where water for the bread making was stored. The flint face of the Village Shop was repeated when Teapot Row was built at a later date.

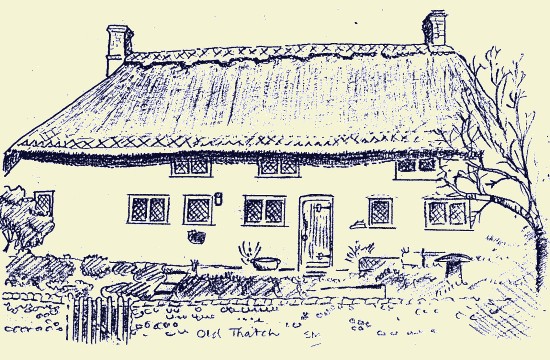

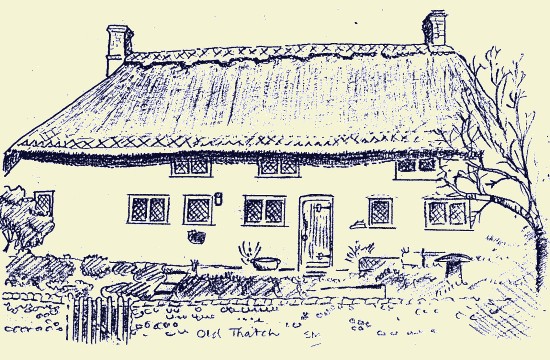

To the left of Teapot Row is Old Thatch. If you look closely you can see where four original cottages have been joined into one residence. This was made possible because the building was originally a hall open to the thatch with no chimney but a hole in the roof for the smoke to escape through. The roof beams are covered in soot as a consequence. The building was added to with an extension to the right of the present front door in brick. The original building was timber framed and some of the lath and daub sections are visible at the rear. Fire destroyed the front at some time and it was replaced with flints. The house has a large inglenook fireplace, reputed to be the only one in the village which does not smoke. The old well in the front garden has been covered with a pond and the water table is eighteen feet below, the usual well drop for the village. The front windows were originally small, square panes, apparent where the window bars have been cut off to make way for the present diamond shaped, leaded lights, inserted during the twenties.

Opposite is Arbor Vitae, a long cottage, three rooms wide, again half-timbered and painted black and white. Some of the windows have old glass in diamond-leaded panes. The front has been extended eastwards. This house was also used for a time as a weekly doctor’s surgery.

Next door, hiding its age behind a Georgian facade, is Laurel House built over a brick-arched cellar. It has a double pitched roof suggesting one house built in front of another. The Marchant family who lived here in the last century were famous for their eccentricity and are recorded as living in the area since about 1600.

Primrose Cottage next door takes its name from the Primrose League connection with the fountain opposite.

Septima Cottage, next door with its roof covered in an attractive creeper, vies with The Old Farm House to be the village’s oldest building. It has the original brick floors on the ground floor laid on puddled clay. The upper floors have broad 18 inch boards and are a mix of oak and chestnut. The roofing tiles are mainly original and are pegged to oak battens with oak pegs. Two windows have original leaded lights with flint glass. The original bread making oven is well preserved. One original staircase was still in use in 1950. Inside partition walls are of plaster and lath between original oak puncheons. The cottage’s name came from Ann Septima Cuttress who later became Mrs Benjamin Baldy. She lived in the house from the age of six as a girl, wife and widow and had fifteen children. She lived to the ripe old age of eighty six and her husband lived for eighty five years.

Now down to the renowned Shepherd and Dog, passing The Old Bakehouse en route. This cottage as so many others in the village has been lovingly restored. This was the home of the Willett family in the 19th century, an energetic and musical family who became the first village bakers and postmasters. They also provided the village cobblers, carters, schoolteachers, and choristers. The business transferred up the hill to the present Village Shop at the turn of the century when Miss Willett married Obadiah Lucas.

0£ all the houses so far described the Shepherd and Dog is the only one visitors can enter and view for themselves. It was originally built as a cottage which a separate brochure describes in more detail. With the backdrop of the Downs rising even more steeply here because of the dip and the gushing stream and ram house, the Shepherd and Dog attracts many visitors. The ram house has nothing to do with sheep but with the pumping of water arranged in 1865 by Henry Willett, a lover of Fulking who was perhaps also related to the Willetts of the village, who took pity on the men and women who carried the water up the steep hill by hand. Henry Willett was a friend of John Ruskin and the benefactor who established Brighton Museum. Together they arranged for the building of the ram which pumped water up the hill in pipes to the villagers, either to their homes direct or to several pumps, one of which is still in evidence opposite to Kent Cottage and another by the telephone kiosk. The text on the ram house was taken from the Book of Psalms and relates to the blessings of springs. Another less obvious erection is the glazed fountain opposite to Primrose Cottage. As the spring never dries and as the cost of the ram and piping was paid for by public subscription, the village of Fulking was supposed to have free water provided in perpetuity. What happened when Fulking was put onto mains water in 1951 is another story.

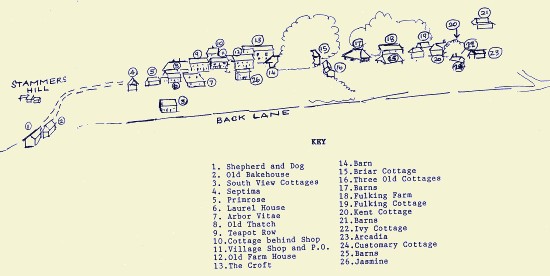

The walk has covered houses in the designated conservation area where fewer than one third of the people of Fulking live. There are communities in Stammers Hill and in the village end of Clappers Lane. Many individual houses and several oustanding farm houses are also within Fulking but somewhat further out. Clappers Lane would make another interesting walk. It has been described as a much-used smugglers route and in an area devoid of hedges it is surprisingly well covered by over-arching trees and bordered by high hedges. But for now I leave you at the end of the Street by the famous Fulking spring.

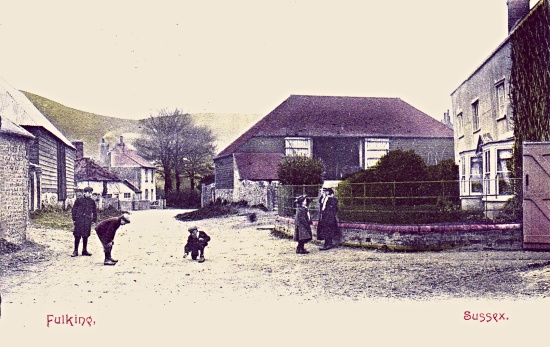

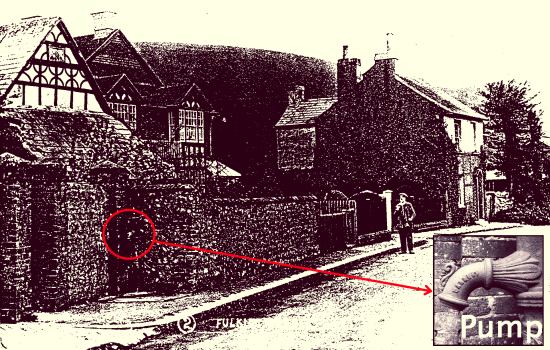

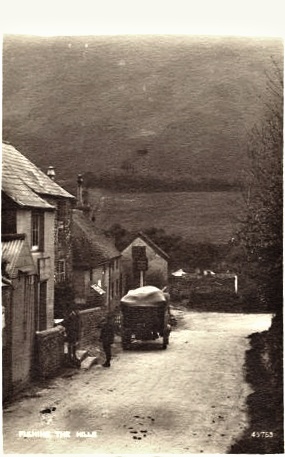

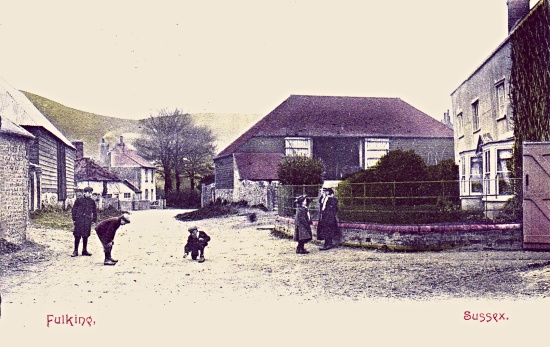

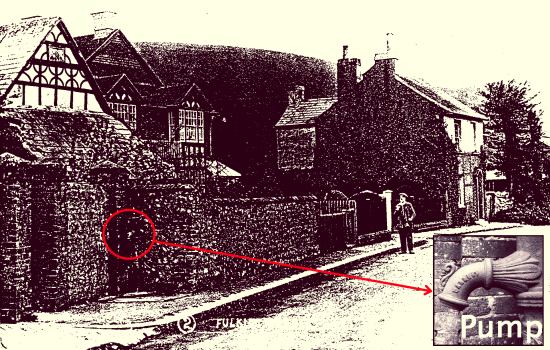

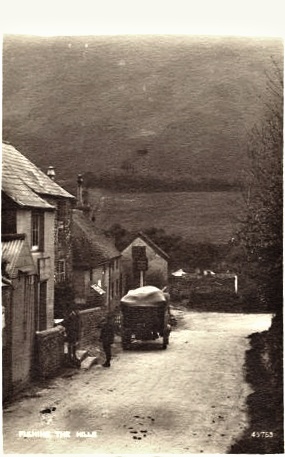

Some old views of The Street, Fulking

Children playing in front of the barns beside Fulking Farm on the right. Briar Cottage is in the distance on the left. The barn on the left made way for Thatchly and the large barn on the right for The Keep and Coombes. The wall immediately on the left belonged to Kent Cottage but now fronts Chimney House.

A clearer view of Briar Cottage with the three old cottages in front which made way for Fulking House. The wall on the immediate left belonged to Customary Cottage.

Customary Cottage, Fulking House and Briar Cottage. The water pump is still there.

The picture gives a good impression of the pace of life in Fulking around 1930. The Chapel of Ease is on the right and all the buildings beyond Briar Cottage are still there, but the pillars and railings on the right have been rearranged.

This picture from around tbe turn of the century outside Old Thatch, shows three of the previous four cottages. The shop has not yet developed a bay window, but parking is beginning to be a problem!. Across the road from the shop is a stable demolished in living memory, which partially hides Jasmine before its extension. A clear gap remained between Jasmine and Briar Cottage. The roof of Customary Cottage, temporarily called Ivy Cottage, shows behind Briar and then only barns are visible until the big chimney stack of Kent Cottage at the far end.

This picture shows a boy wagoner with probably the carter himself outside the old shop and Post Office just above The Old Bakehouse. This building is now demolished. Beyond is the Shepherd and Dog before the dormer windows were put in the roof. The vegetable patch in front of the pub is discernable, where the current car park is located. The previous carved pub sign board is also visible.

Stuart Milner, 1987

Currently popular local history posts:

Villagers recall that

Villagers recall that