Category: Edburton

Will the Germans target Edburton?

The Local reports:

German inventors unveiled a drone carrying a defibrillator on Friday which they hope will be able to save the lives of heart attack patients. .. [They] hope that a drone will be able to deliver a defibrillator to revive the patient quicker than an ambulance. .. It has been designed to reach patients in remote areas and is activated by the emergency services or members of the public through a mobile phone app .. which when activated would start the drone and bring the defibrillator to the GPS coordinates of the patient. The downside is that the drone relies on someone being with the heart attack victim and having the app downloaded on their phone. .. The drone on display on Friday had eight rotor blades, a diameter of one metre and a flying distance of 15 kilometres. With the defibrillator it weighs 4.7 kg and costs €20,000.

Fulking book benefits Church

I would like to update all those who sponsored or purchased my book [Anthony R. Brooks (2008) The Changing Times of Fulking & Edburton. Chichester: RPM Print & Design] how the proceeds of £3,800 have been spent by the Church.

Originally it was earmarked for a new door to be added to the church entrance. After much thought the PCC decided that as the Church is used during the winter months twice a month for a maximum of two hours, money spent on a new door would not be cost effective. So a compromise was agreed:

- A warm air unit would be fitted over the church door inside.

- The entrance path to the church has been reshaped to include a patio to give more standing area.

I am pleased to say both projects are now complete.

[from Pigeon Post, August 2013]

Residential continuity in the nineteenth century

If you wander around the churchyard at St. Andrew’s peering at graves, you will soon get the impression that certain families persisted in the parish over several generations. But many of the older graves are hard to read and some are missing altogether. To get a more accurate sense of how many residents had parents who also lived in the parish, we need to turn to the nineteenth century census returns. The first ‘modern’ census, in 1841, only asked respondents if they had been born in the county in which they were then living. But the 1851 and subsequent censuses asked for both the county and the parish of birth. These later censuses thus permit a rather fine-grained analysis of the relation between where people were living and where they were born.

| Year | EdFulk | AdjPar | ElsSus | OutSus | Total |

| 1851 | 57% | 14% | 26% | 3% | 288 |

| 1861 | 41% | 18% | 34% | 6% | 299 |

| 1871 | 41% | 11% | 38% | 10% | 300 |

| 1881 | 41% | 11% | 39% | 8% | 340 |

| 1891 | 39% | 9% | 38% | 14% | 358 |

Where were the residents of the parish born?

In this table[1], the rows correspond to the five censuses that took place in the second half of the nineteenth century. The columns show the census year; the percentage of the parish population who were born in the parish (i.e., in Edburton or Fulking, EdFulk); the percentage who were born in one of the immediately adjacent parishes (AdjPar), i.e., Poynings, Portslade, [Old] Shoreham, [Upper] Beeding, Henfield or Woodmancote; the percentage who were born elsewhere in Sussex (ElsSus); the percentage who were born outside Sussex (OutSus); and the total size of the population in the census year.

The first row is perhaps the most striking. In 1851, over 70% of the residents of the parish were living within easy walking distance of where they were born (i.e., in Edburton or Fulking or one of the immediately adjacent parishes) and only 3% had been born outside Sussex. By the last decade of the century, the corresponding figures were 48% and 14%, respectively, and the size of the local population had increased by nearly 25%.

The remaining four rows are notable more for their similarity each with the next than for any radical changes. As the total population increases, the proportion of residents born in the parish remains more or less constant, as does the proportion born in Sussex but outside the immediate area (ElsSus). The proportion born in the immediately adjacent parishes halves over the 1861-1891 period whilst the proportion born outside Sussex more than doubles.

The first table provides a good sense of where the population had come from in any given census year but it does not give us a sense of the family structure of the parish. To get that, we need to look at the way the main resident families[2] persisted over time:

Families resident in the parish for five contiguous censuses

These eighteen (extended) families comprised nearly two thirds of the population of the parish in 1851. By 1891, that proportion had declined to one third. The overall picture is thus rather what one would have expected: over the course of the second half of the nineteenth century, the outside world gradually made its presence felt in what had hitherto been a somewhat isolated rural parish.

Footnotes

[1] A couple of rows sum to 99% rather than 100% as a consequence of rounding.

[2] Family members are defined here by surname, not genetics. If Jane Paine marries Bert Burtenshaw and remains in the parish then she will be counted as a Burtenshaw, not as a Paine, in the following census. Where the census takers used alternant spellings for a surname, both are listed in the table.

References

- Marion Woolgar (1995) Census transcriptions and surname index for Edburton & Fulking. Published by the Sussex Family History Group.

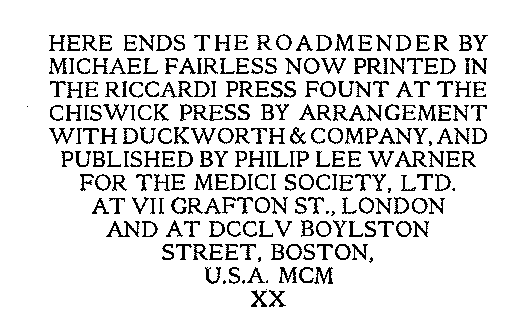

The Roadmender Myth

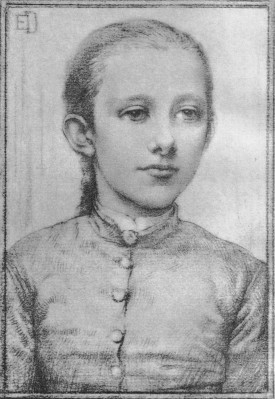

(drawn from a photograph)

Although The Roadmender is suffused with a sense of location it is, more often than not, inexplicit as to exactly which locations the author had in mind [1]. But readers, reviewers, book illustrators and authors of travel guides are curious about such matters. They had to wait ten years even to discover who the author was. That information was released in 1912 by her literary executor, against the author’s express wish, as an antidote to the misinformed speculation that had developed around the book. One reference in the book was unambiguous even before her identity became known — from the house in Shermanbury she reports hearing the bells of “the monastery where the Bedesmen of St. Hugh watch and pray” (page 44). Other references, to the Thames and the Downs are less specific. Books with titles like The Roadmender Country (Lorma Leigh, 1922) and The Roadmender’s Country (George Bramwell Evens, 1924) were published to sate the geographical curiosity of her readers some two decades after the book that inspired them was originally published.

The location that concerns this post is the subject of the following passage:

On Sundays my feet take ever the same way. First my temple service, and then five miles tramp over the tender, dewy fields, with their ineffable earthy smell, until I reach the little church at the foot of the grey-green down. Here, every Sunday, a young priest from a neighbouring village says Mass for the tiny hamlet, where all are very old or very young — for the heyday of life has no part under the long shadow of the hills, but is away at sea or in service. There is a beautiful seemliness in the extreme youth of the priest who serves these aged children of God. He bends to communicate them with the reverent tenderness of a son, and reads with the careful intonation of far-seeing love. To the old people he is the son of their old age, God-sent to guide their tottering footsteps along the highway of foolish wayfarers; and he, with his youth and strength, wishes no better task. Service ended, we greet each other friendly — for men should not be strange in the acre of God; and I pass through the little hamlet and out and up on the grey down beyond. Here, at the last gate, I pause for breakfast; and then up and on with quickening pulse, and evergreen memory of the weary war-worn Greeks who broke rank to greet the great blue Mother-way that led to home. I stand on the summit hatless, the wind in my hair, the smack of salt on my cheek, all round me rolling stretches of cloud-shadowed down, no sound but the shrill mourn of the peewit and the gathering of the sea. [The Roadmender, pages 10-11]

Over the last hundred years, it has been widely assumed, by those who have had occasion to care about such matters, that “the little church at the foot of the grey-green down” is St. Andrew’s at Edburton. Writing in the Observer in 1921, Arthur Anderson made the claim explicitly. Such was also clearly the working assumption of Will F. Taylor, the photographer who did the illustrations for a 1922 US edition published by E.P. Dutton and whose image of St. Andrew’s can be seen at the top of this post. In the 1950s F.A. Howe, who lived right next door to St. Andrew’s, reported that devotees of the book would occasionally turn up at the church. The 1999 edition of Tony Wales’s survey of West Sussex villages provides a modern example and is quite explicit: “St. Andrew .. is the little grey church in Michael Fairless’s strange Sussex book” (page 90).

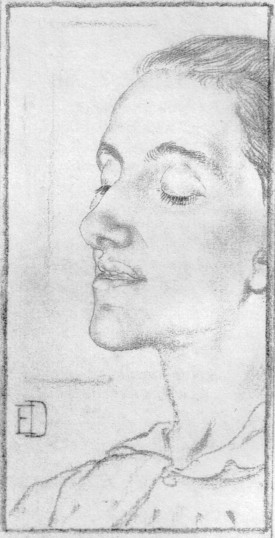

(drawn from life by Elinor Dowson)

As Howe notes, Anderson was to withdraw his claim just three years after he originally made it:

When I wrote my Observer articles, I hazarded the suggestion that this little church could be no other than Edburton, which fits, and alone fits, the geographical conditions, but I have learned since that though Michael Fairless had in mind an actual church it was one in another English county, far from Sussex. My suggestion has, however, not only been adopted by others; it has been expanded into an assertion that Michael Fairless herself often kneeled before the altar here [2]. For this statement there will henceforth be no warrant, though I daresay the suggestion, once having been made, will still be repeated and to Edburton will still be attributed this association. [Quoted by Howe 1958, page 61.]

Anderson is probably incorrect in taking full responsibility for the original claim — others surely made the same inference that he had. But his pessimism about ever getting it corrected it was clearly appropriate. The myth lives on.

Footnotes

[1] Likewise, the book rarely names contemporary figures. But MB makes an exception for John Ruskin who had died at exactly the point that she had begun writing The Roadmender. She seems to have had no fear about encountering him in the hereafter:

John Ruskin scolded and fought and did yeoman service, somewhat hindered by his over-good conceit of himself. [The Roadmender, page 139]

[2] And, of course, MB’s grave is not to be found in the churchyard at St. Andrew’s, Edburton. There is no reason for it to be there. It was her wish that she be buried at St. Giles, Shermanbury but the old churchyard was closed for interments at the time of her death (The Landmark VI.1, 1924, page 602). Instead, her grave is to be found at St. James, Ashurst.

References

- Alan Barwick (2013) “Notes for The Roadmender talk”. Henfield Museum: manuscript. [This paper is the single best source for the biographical details of MB’s brief life and is based, in part, on a recent bequest of documents to the museum. The illustrated talk itself includes a remarkable collection of modern and historical images that document aspects of that life.]

- Michael Fairless (1902) The Roadmender. London: Duckworth. [As noted in the text above, the book remains readily available. You can also download it as a PDF file, or read it on the web.]

- F.A. Howe (1958) A Chronicle of Edburton and Fulking in the County of Sussex. Crawley: Hubners Ltd, page 61. [Howe’s single paragraph on this topic inspired the present post — which also borrows the section title he used in his contents list.]

- W. Scott Palmer & A.M. Haggard (1913) Michael Fairless: Her Life and Writings. London: Duckworth (PDF). [The first author was MB’s close friend and literary executor, Mary Dowson, and the second was MB’s eldest sister. The book includes two portraits of MB by Elinor Dowson, both reproduced above. MB was known as Marjorie Dowson for the final few years of her life.]

- Tony Wales (1999) The West Sussex Village Book. Newbury: Countryside Books, page 90.

Currently popular local history posts:

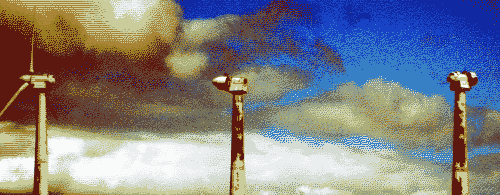

Rampion DIY Guide

If you wish to make representations to the Planning Inspectorate about the Rampion trench, then the Royal Yachting Association offers a handy DIY guide. The deadline is 11th May.

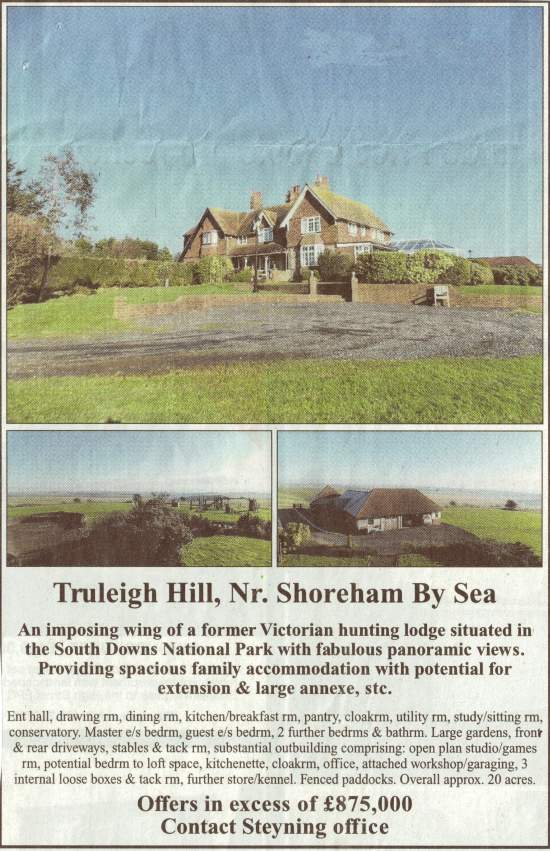

On the market

Damage to the Beeding Hill to Newtimber Hill SSSI

Natural England, the responsible body for Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs), reports that “the site has been blighted by off-road motorcyclists who have been using it as a track. Damage to the site is worsening over time, with offenders bringing equipment with them to dig tracks and make alterations to suit their sport. .. the area is now being monitored by local police officers in a bid to stop the damage. .. A 23-year-old man from Hove has recently been issued with a warning under the Wildlife and Countryside Act, after being arrested causing damage at the site”.

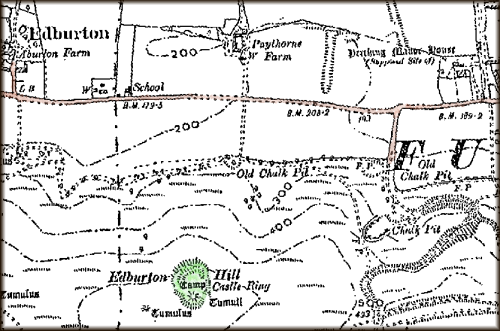

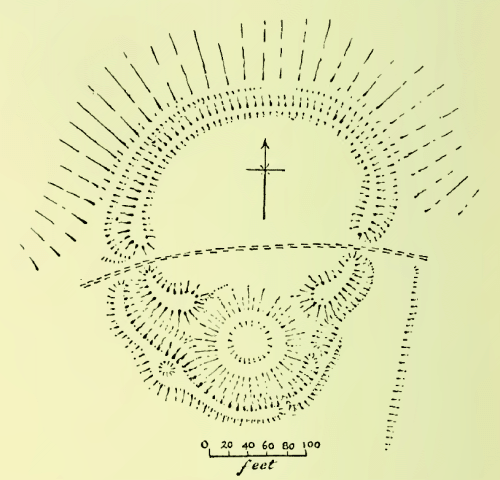

Castle Ring

Castle Ring[s], also known as Edburton Castle or Edburton Camp, sits at the peak of Edburton Hill on the Downs halfway between Fulking and Edburton. It cannot be seen from the road. It can just be seen from the South Downs Way as you descend the western slope of Perching Hill, but only if you already know what you are looking for. There is no marked footpath to it. Getting there entails a steep climb across a field. But it is worth the effort. The structure itself, which has ‘scheduled monument’ status, is impressive and the views over the Weald are the equal of those from the Dyke.

Castle Ring has not been excavated and rather little is known about it or what it was for. Even the date of construction is uncertain although most sources point to the end of the 11th century, immediately after the Norman conquest. Volume 1 of the Victoria County History, published in 1905, refers to it as “this curious little work” and remarks that:

There no traces of masonry, and, as far as one can see, there is no supply of water near. Why it should be placed here is a mystery, unless, indeed it was a signalling station visible perhaps from Pulborough and Knepp Castle.

[Page 1905, page 476]

Volume 7, published in 1940, is likewise terse:

It has a very small rectangular bailey [= external wall], and an equally insignificant motte [= mound]. It is probably an outpost castle constructed soon after the landing in 1066. The boundary of the rape [= administrative district], and the division between East and West Sussex, passes immediately to the west of the motte ditch.

[Salzmann 1940, page 202]

Hadrian Allcroft’s magisterial Earthwork of England, published in 1908, still provides the most comprehensive archaeological description and discussion of the site:

Edburton Camp crowns a prominent hill-bastion of the northern face of the Downs .. In position it resembles Chanctonbury, as also in having one vallum [= earth rampart] and one fosse [= trench or moat], but it is singularly small even for a Sussex fortress, measuring no more than 60 yards across the widest diameter of the diminutive area, and in plan is quite unlike any other hill-top fortress. The line of the defences follows the oval contour of the exiguous hill-top on all except the southern side, where it is interrupted by a depressed mound of 100 feet in diameter, the fosse looping outwards to cover the base of the mound. The whole plan, therefore, is at first sight much that of the simplest form of mount-and-bailey fortress. But on close examination this resemblance will be found to be less real than apparent: the mound is too low to have been a motte, for it does not attain even to the 10 feet or so of vertical height reached by the vallum on either side of it, and it can never have been much higher than it now is, for had it been greatly wasted the fosse along its southern side must have been far less deep than now, and the depression at its centre must have disappeared. More important still, the fosse is not carried round the northern side of the mound, and apparently never was. The vallum to east and west rises to more than average height, but ends abruptly, neither reaching to the mound nor being continued round its base. A shepherd’s path traverses the area, passing the vallum by openings seemingly both original in the eastern and western sides. From the western entrance commences a second vallum, which follows the edge of the fosse right round the southern angle of the camp and then gradually disappears. It is at its highest in the angle where the fosse bends to accommodate the mound, and at this point is a circular depression about 8 feet wide in its broad summit. The great mound is neither flat-topped nor ringed by a vallum, but in its centre has a cup-shaped basin 33 feet in diameter and perhaps 3 feet deep. The ground to the south of the camp is to all intents level, but there are no signs of any outworks, unless a small and low mound 80 yards to the south-west be such. From the eastern entrance, where the slope is steeper, a very slight scarp is traceable for some 40 yards in a direction west of south. It is perhaps an old plough-mark. Fragments of pottery are to be found in the mole-casts along it. Further to the west lie several barrows which have yielded very early remains.

Of all the South Down camps this is the most puzzling: it would indeed be difficult to find another like it anywhere. It has been said of it that it “has nothing in common with the hill-forts (of Sussex).” One would rather say that it has everything in common with them except the mound. The nearest analogy to the mysterious mound with its depression is that within the area of Mt. Caburn, which would seem to have been a reservoir. It is much to be regretted that Pitt-Rivers, who explored the one, did not examine the other also; and small as Edburton Camp is, the task of exploring it completely would be an easy one. Meanwhile there is nothing but conjecture. Some have suggested that the mound was a beacon. If that were so, what was the need of the rest of the earthworks? Yet they are all apparently of one plan with the mound and of one date. Others believe it to be a Norman fortress; but against this is the absence of any encircling fosse about the whole of the mound, quite apart from the exceptional character of the site, at an elevation such that no water can have been found within several hundreds of feet at any time during many centuries past. Edburton must remain a mystery until the spade is brought to unlock its secret.

[Allcroft 1908, pages 659-662, footnotes omitted]

Recent reference material (i) lists the structure as “Early Medieval/Dark Age — 410 AD to 1065 AD” but then immediately goes on to say that it is believed to be Norman; (ii) claims that the central depression resulted from “mistaken barrow digging in the 19th century” but offers no evidence for this speculation; and (iii) suggests that the use of Castle Ring was “more likely to have been administrative and residential” than military but fails to address the implications of the apparent absence of any water supply. It seems that Allcroft’s conclusion — “Edburton must remain a mystery until the spade is brought to unlock its secret” — is as true today as it was more than a century ago.

References and further reading:

- A. Hadrian Allcroft (1908) Earthwork of England. London: Macmillan, pages 659-662.

- William Page, ed. (1905) The Victoria History of the Counties of England, Sussex, Volume 1. London: Archibald Constable, page 476.

- L.F. Salzman, ed. (1940) A History of the County of Sussex, Volume 7: The rape of Lewes. London: Victoria County History, page 202.

- Edburton Castle Ring — Books and Resources.

Currently popular local history posts:

History of Local Names

Paythorne

The oldest surviving spellings all suggest that Paythorne is named from a thorn-tree (hawthorn) associated with a Saxon man named Paga. This should have come to be pronounced “Pawthorn”, and documentary records right through to the 19th century prove that that is what happened. The alternative and current name is suggested by the Peathorne found in 1830, if the ea is as in steak, and it has not been explained. It may have been due to someone’s knowledge of the place called Paythorne on the Yorkshire-Lancashire boundary near Gisburn.

Pauethornam (Latin) in late 11th cent., Pagethorne in 1288, Pawthorne in 1633

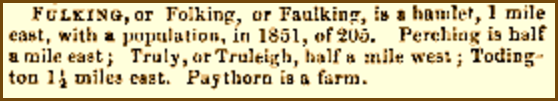

Fulking

Fulking is an Anglo-Saxon name in –ingas, like Hastings, originally a name for a group of people but applied to a place (rather like Sussex ‘the South Saxons’). At Fulking, they were people associated with a man named Folc or Folca whose name meant ‘folk, people’, who is unknown to history. This name is not recorded by itself, but it occurs as the first element of names like Folcbeorht and Folcwine, and in Norman names like Fulk(e) which spring from the continental relative of the same element. In Hastings, the –s of –ingas has been retained, but in Fulking it has disappeared, and that is in fact what usually happens. Historians used to talk about the men whose names appear in place-names like this as tribal leaders or founding fathers of families, but we actually have no idea what relation the person bore to the group: father, godfather, hereditary or chosen leader on the basis of military or agricultural prowess, entrepreneur, slave-owner, or whatever: hence the vague “associated with”.

Fochinges in 1086, Folkinges in about 1091 and in 1260, Folkyngge in 1244, Fulkyng in 1327

Perching

Perching is a very difficult name whose origin is not known for certain. It seems to be an –ingas name like Fulking, but there is no known Anglo-Saxon personal name to suit the first part. If one were really clutching at straws, one might see a survival of the Roman name Poricus seen in that of the statesman Marcus Poricus Cato and members of his clan, which would reach the required form through known sound-changes in British Celtic and Old English. It may be an unrecorded Old English *perec (pronounced “PERRetch”) which could be an ancient English borrowing of Latin parochia ‘parish’, though there is no obvious reason for that. It might represent a variant *perric of the word pearroc, the source of park and paddock (and possibly itself derived from parochia), though what ‘people of the paddock’ might imply is equally obscure. It might not be an –ingas name at all, but a plural of a derivative of this word, *perricingas ‘the railed or fenced areas’. In this respect, it is interesting but probably misleading that in medieval times land was held of Perching manor for the service of fencing Earl Warenne’s deerpark in Ditchling.

Berchinges, Pʼcinges in 1086, Percinges generally in early Middle Ages, Perchinges in 1327

Truleigh

Truleigh was until recently pronounced “true lie”, with the stress on the second syllable, a curiosity of Sussex, mainly Wealden, names containing Old English lēah ‘wood, clearing’ which dates back some 500 years. It has been claimed that the first element is trēo(w) ‘tree’, the whole meaning ‘clearing marked by a tree or trees left standing’. That is not linguistically impossible, but it seems much more likely to contain Old English trēow or trūwa, meaning ‘truce’, with reference to unknown historical events. Its position less than a mile from the boundary separating historic West and East Sussex (Bramber and Lewes rapes) may be relevant.

Truleg’ in the 13th cent., Treweli in 1261, Treule in 1281 (Trailgi in 1086 is misleading)

Edburton is the farm or village of a woman named Ēadburg ‘wealth fortress’, whose identity is unknown. She is more likely to have been an overlord than an actual farming tenant or free peasant, but we cannot be sure. There were many prominent Anglo-Saxon women with this name. Since at least the 13th century the village was known as Abberton, and this pronunciation is retained in the name of Aburton Farm, the manor farmhouse.

Eadburgeton in the 12th cent., Adburghton in 1261, Ebberton in 1357, Abberton in 1377, Aberton alias Edberton in 1584

Tottington

Names formed with Old English -ingtūn are usually interpreted as ‘farm or village associated with a person called X’, and they are believed to date from a later period in settlement history than the –ingas type. X in this case is generally thought to be Totta, not a recorded Anglo-Saxon male name but occurring in enough Sussex place-names to make it a reasonable supposition. On the other hand, Tottington is sited just under a spur of the South Downs from which there is a spectacularly wide view over the Weald, Bramber and the opening of the Adur valley, which leads to the suspicion, supported by early spellings, that it is really Tōting-tūn ‘farm at the toot or lookout point’.

Totintune in 1086, Totington in 1291, Totyngton in 1294

References

- Richard Coates (1980) A phonological problem in Sussex place-names. Beiträge zur Namenforschung, new series 15, 299-318. [On the stress problem illustrated in Truleigh.]

- Allen Mawer & F.M. Stenton (1929-30) The place-names of Sussex. Cambridge: CUP (for the English Place-Name Society, Survey volumes 6 and 7). [Standard county work.]

- L.F. Salzman, ed. (1940) [Victoria] history of the county of Sussex, vol. 7: Rape of Lewes. Oxford: OUP. [Standard county work.]Copyright © Richard Coates, 2012