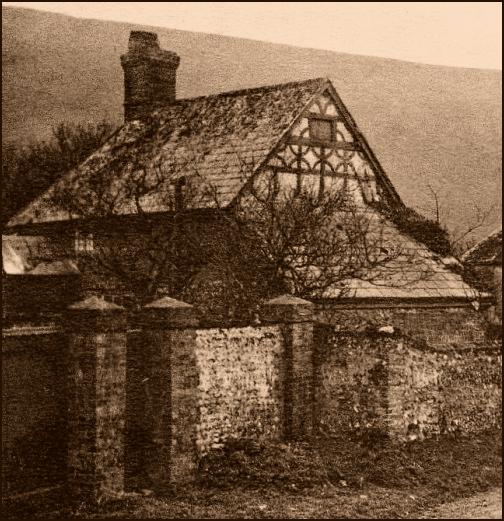

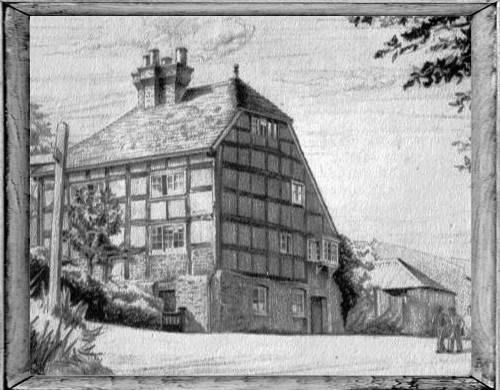

A particularly fine specimen of half timbered architecture stands prominently at the entrance to the Village High Street of Fulking. Although some of the older inhabitants of the village recall its name as Kent Cottages, for there were originally two cottages but now joined into one, there seems to be no record of the change in the construction or its name.

The main part of the building dates from 1600 and one can easily detect the old portion as distinct from the more modern side — the lofty structure is raised over a basement, above which are two floors and is constructed entirely of timber framing in large braced panels.

Through the ages several interior alterations have been made, none of which have added to its original charm, although they have not destroyed the original structure.

Over the cellar remain the ‘Parlour’ with its outshut and large open fire-place with cambered and stop chamfered chimney beam, and a half bay on the other side of the chimney stack: in the sides of the chimney shaft still remain the large wrought iron hooks from which the huge joints of pork were hung to ‘smoke’. The beams on the first floor are all stop chamfered.

Little is known of this delightful old building and it would prove interesting reading if its history could be compiled: many of the inhabitants of Fulking have in fact lived in this house at one time or another and can recall earlier days when it was used as the Village Infirmary.

The building is far from being in good state of repair and we can only hope that it is not allowed to fall into decay

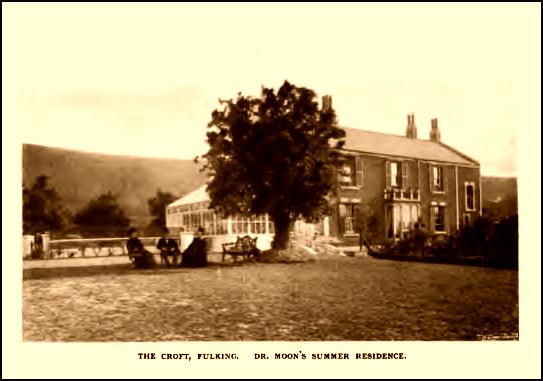

In a commanding position at the entrance to the village from the east, on the south side, is Kent House, of about the year 1600. It is a lofty and imposing timber-framed building in large braced panels and consists of two storeys and an attic. The slope of the site is dealt with by the addition on the north side of a kind of undercroft. The south side of this chamber is a wall of the solid chalk along which rests an immense beam on which rests the interior timber framing of the floors above. Formerly it was known as Kent Cottages and was at that time two dwellings. Inhabitants now living say that their parents remember its being used as a poor law infirmary. [Howe 1958, page 32]

At some point during the last fifty years, the name of this Grade II listed building reverted to Kent Cottage, despite it being the tallest and one of the most striking houses in the village. It was once part of a two bay house and what we see today are the remaining one and a half bays of the original house. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, following the introduction of the Poor Law Amendment Act in 1834, it was used as a workhouse as well as an infirmary.

Many original features have been retained throughout the various changes documented above, including exposed beams and large open fireplaces in most rooms, even those in the attic. Consequently, a large chimney, some nine foot square, runs through the centre of the house to serve all these fireplaces. Along with this, a series of very steep, narrow staircases lead to the attic passing through the rooms on the upper floors, which greatly reduces the room sizes and gives the interior a quaint and unusual atmosphere. Over the years the external façade and historic character of the building has remained largely unchanged, apart from the addition of a conservatory tucked away on the south side of the building, which was added in 2003 and complements the interior of the house.

References

- Unknown author (1950) “Kent House”, St. Andrews Quarterly 6, pages 13-14.

- F.A. Howe (1958) A Chronicle of Edburton and Fulking in the County of Sussex. Crawley: Hubners Ltd.

[Copyright © 2012, Anthony R. Brooks. Adapted from Anthony R. Brooks (2008) The Changing Times of Fulking & Edburton. Chichester: RPM Print & Design, pages 161-162.]

Currently popular local history posts: